Method to Madness: North Korea and the ‘Madman’ Theory

Published 10 Aug 2017

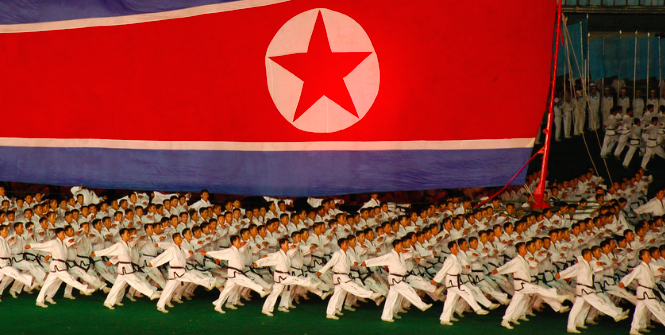

North Korea is routinely characterised by western leaders and the global media as an irrational actor in world politics – a rogue state that acts entirely on dangerous and destabilising impulse. Pyongyang’s bellicose rhetoric and frequent sabre-rattling often seem to lack any clear strategic direction beyond pushing the Korean peninsula closer to war and satisfying the militaristic ego of its despotic leader. However, such characterisations are far too simplistic, and there is indeed a calculated strategic rationale to North Korea’s politics of provocation.

US President Richard Nixon is widely associated with his development and employment of the ‘madman’ theory of international diplomacy. During his presidency, Nixon made aggressive unpredictability a central feature of his administration’s foreign policy – allowing, for example, the North Vietnamese leadership to believe that he was willing to employ nuclear weapons to bring an end to the Vietnam War.

This policy served to keep the United States’ primary rival, the Soviet Union, in a state of uncertainty over American intentions. In 1969, the Nixon administration unexpectedly exercised America’s strategic nuclear forces and raised its DEFCON status – a move which alarmed the surprised Soviets. Melvin Laird, the Secretary of Defence under Nixon, would later claim that Nixon wanted his Russian rivals

“to have the feeling that you could never put your finger on what he might do next”.

This policy served to keep the United States’ primary rival, the Soviet Union, in a state of uncertainty over American intentions. In 1969, the Nixon administration unexpectedly exercised America’s strategic nuclear forces and raised its DEFCON status – a move which alarmed the surprised Soviets. Melvin Laird, the Secretary of Defence under Nixon, would later claim that Nixon wanted his Russian rivals

“to have the feeling that you could never put your finger on what he might do next”.

In this respect, the North Korean leadership is an adept pupil of Nixonian foreign policy. Whilst the US and its allies frequently label North Korean conduct as “irrational”, this is a mischaracterisation of North Korean actions. They are undeniably provocative – often dangerously so. But they are underpinned by a logical strategic calculus that is far from irrational.

To understand the rationale behind North Korea’s strategy of provocation and nuclearization, one must understand the goal that underpins every action undertaken by the North and its ruling regime: self-preservation. In international relations, all states pursue goals that ensure their survival against potential existential threats, and in this regard North Korea is no different from any other country.

So why is Pyongyang intent on employing its own nuclear ‘madman’ policy to ensure this survival?

Despite its confrontational rhetoric and propaganda, Pyongyang is well aware that a war with the United States and South Korea is almost certain to result in defeat. Its military – although the fourth largest in the world – relies on outdated equipment and likely lacks the logistical capabilities to sustain this force in the field for a prolonged campaign, meaning any conventional conflict against the better-equipped South and its allies is unlikely to go favourably for North Korea.

To understand the rationale behind North Korea’s strategy of provocation and nuclearization, one must understand the goal that underpins every action undertaken by the North and its ruling regime: self-preservation. In international relations, all states pursue goals that ensure their survival against potential existential threats, and in this regard North Korea is no different from any other country.

So why is Pyongyang intent on employing its own nuclear ‘madman’ policy to ensure this survival?

Despite its confrontational rhetoric and propaganda, Pyongyang is well aware that a war with the United States and South Korea is almost certain to result in defeat. Its military – although the fourth largest in the world – relies on outdated equipment and likely lacks the logistical capabilities to sustain this force in the field for a prolonged campaign, meaning any conventional conflict against the better-equipped South and its allies is unlikely to go favourably for North Korea.

Nuclearisation therefore provides a power leveller against the greater conventional capabilities of its opponents, and from a North Korean perspective is entirely rational. Direct US military action in Iraq, Libya, and most recently against the Assad Regime in Syria, have only further fuelled North Korean fears of this power imbalance and provided salutary lessons for what happens to America’s rivals who lack a nuclear deterrent.

Of course, a nuclear deterrent only works if your enemies believe you’re willing to use it – and this is where the ‘madman’ aspect of North Korean diplomacy comes to the fore.

Military provocations by the North – such as the 2010 sinking of the South Korean naval vessel Cheonan and shelling of the island of Yeonpyeong – are examples of this approach. By acting in a manner that its opponents regard as irrationally belligerent and dangerous, North Korea can cultivate a perception of unpredictability that forces its enemies to remain cautious and measured in their response.

This strategy has worked – so far – because North Korea has calculated that the US and South Korea are reluctant to enter into an open conflict. Despite the likelihood of their eventual victory, the cost of a war with North Korea would be staggering to both nations in terms of lives and resources. This is to say nothing of the possibility that China may be dragged into the conflict.

Of course, a nuclear deterrent only works if your enemies believe you’re willing to use it – and this is where the ‘madman’ aspect of North Korean diplomacy comes to the fore.

Military provocations by the North – such as the 2010 sinking of the South Korean naval vessel Cheonan and shelling of the island of Yeonpyeong – are examples of this approach. By acting in a manner that its opponents regard as irrationally belligerent and dangerous, North Korea can cultivate a perception of unpredictability that forces its enemies to remain cautious and measured in their response.

This strategy has worked – so far – because North Korea has calculated that the US and South Korea are reluctant to enter into an open conflict. Despite the likelihood of their eventual victory, the cost of a war with North Korea would be staggering to both nations in terms of lives and resources. This is to say nothing of the possibility that China may be dragged into the conflict.

The cost of such a pyrrhic victory would undeniably outweigh its benefits to the US and its allies, and Pyongyang knows and bases its strategic calculus on this cost/benefit analysis. These actions also perpetuate the siege mentality that permeates North Korean society, allowing the Kim’s to maintain a tight grip on domestic power through constantly reinforcing the fear of foreign invasion.

None of this is to say that rational decisions are correct decisions. History has shown that miscalculated strategic rationales can have disastrous consequences – the outbreak of the First World War was, after all, a consequence of a series of alliances rationalised on the grounds of ensuring a balance of power that was intended to deter conflict.

Interestingly, many commentators have noted that the Trump administration’s foreign policy, whether intentionally or otherwise, has increasingly appeared to take on a Nixonian character. Military action in Syria, intended to serve as a message to the Assad regime and its Russian allies, and his confrontational rhetoric regarding a wide range of international issues bears the characteristic unpredictability intended to cause America’s rivals to think twice before crossing the United States. Whether Trump’s oft-changing and frequently inconsistent foreign policy is part of a calculated madman strategy or not, the effect is the same – the United States’ rivals (and its allies, for that matter) are having trouble predicting its potential response to confrontation.

None of this is to say that rational decisions are correct decisions. History has shown that miscalculated strategic rationales can have disastrous consequences – the outbreak of the First World War was, after all, a consequence of a series of alliances rationalised on the grounds of ensuring a balance of power that was intended to deter conflict.

Interestingly, many commentators have noted that the Trump administration’s foreign policy, whether intentionally or otherwise, has increasingly appeared to take on a Nixonian character. Military action in Syria, intended to serve as a message to the Assad regime and its Russian allies, and his confrontational rhetoric regarding a wide range of international issues bears the characteristic unpredictability intended to cause America’s rivals to think twice before crossing the United States. Whether Trump’s oft-changing and frequently inconsistent foreign policy is part of a calculated madman strategy or not, the effect is the same – the United States’ rivals (and its allies, for that matter) are having trouble predicting its potential response to confrontation.

Nuclear brinksmanship is a zero-sum game, and the stakes are invariably raised when one player is bluffing. If your opponent, at the very least, slightly suspects that you may not be bluffing, then they may seriously reconsider the costs and risks of attempting to call the bluff. North Korea’s madman approach therefore only works when its rivals respond with rational and predictable caution.

When both players are using the madman bluff however, the game becomes that much more dangerous.

When both players are using the madman bluff however, the game becomes that much more dangerous.