Japan’s Unnecessary Election

Professor Aurelia George Mulgan examines why Japan’s upcoming election is unnecessary and an act of political opportunism.

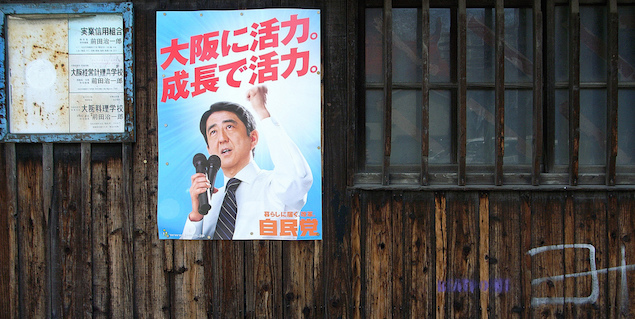

Prime Minister Abe is subjecting his ruling coalition, and his nation, to an unnecessary election on 14 December 2014. Abe claims his decision is all about policy, but in reality it is all about politics. His stated rationale for calling the election is the need to secure voters’ endorsement of his administration’s decision to postpone the consumption tax rise to 10 per cent until April 2017. But his real reasons are based on cold calculations of political self-interest.

First and foremost, Abe is hoping to extend his term of office to six years. This has always been his goal, and he is prepared to lose some Lower House seats in order to achieve it. He judges that six years is what he needs to implement his policy agenda. His list includes consolidating policy changes in Japanese defence and security, as well as attempting more difficult changes such as constitutional reform — his principal ideological goal.

Also on the list is reviving the economy, which he understands is the key to his popularity. Abenomics has had mixed short-term success, and Abe realises that the economy is not going to turn around any time soon. This will undermine his administration going into a 2016 election.

Abenomics has not lived up to the marketing hype with which it was sold to the Japanese public. Part of the reason lies in the incomplete and watered-down implementation of the third arrow, structural reform to promote economic growth, which has largely been a flop. Abe’s growth strategy has amounted to lists of long-term policy goals. These have been long on slogans and short on implementation in the face of opposition from vested interests.

Another reason lies in the implementation of the unnamed ‘fourth arrow’ — fiscal reconstruction (code for increasing the consumption tax). This anti-growth component of Abenomics burdens it with mutually contradictory economic programs. Tax increases run directly counter to the fiscal stimulus arrow. The most Abe can claim is his three arrows are ‘on the way to achieving results’ and ‘a virtuous cycle in the economy where company revenue increases, employment expands, wages increase, consumption expands and the economic recovery is just about to be born’, as he said on the early evening TV show NHK News 7. In short, the much-touted economic recovery that was the promise of Abenomics is still just around the corner.

Second, Abe needs to arrest the decline in public support for his cabinet. Unchecked, this would have fuelled unrest in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and possibly undermined his leadership of the party as well as of the administration. If the electorate did not remove him in the 2016 election, then his party might well have. The polls were showing the trend faced by all Japanese governments after a certain period of time, either shorter or longer, down.

A third and related political motivation is Abe’s aim to reshuffle his cabinet; drawing a line under scandals of money politics among the government ministers he appointed. Abe could hardly do this now after having only done so two months earlier in September. It would mean a reshuffle of a reshuffle. The parallels with his 2006–07 cabinet were particularly unfavourable given that they led to his resignation as prime minister at the time. In the current cabinet, the resignation domino threatens to start all over again. By going to an election, Abe can let the voters do his dirty work for him — getting rid of suspect figures such as Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Koya Nishikawa, who is most likely to lose his seat, along with former Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, Yuko Obuchi, who has already resigned from the LDP.

Finally, Abe figures that he can use the tax hike postponement to his political advantage. He can go into the election on the premise of not raising the consumption tax, which he knows is supported by a majority of voters. No opposition party is against the postponement, and this prevents his opponents from using the tax issue to gain electoral traction against the ruling coalition. This is all part of a general strategy to catch the opposition parties on the hop. The Democratic Party of Japan is nowhere near restoring its major party status and will be incapable of making the seat gains necessary to put it back in office.

At present, politicians in the opposition parties are re-sorting themselves via switches in party membership and new electoral alliances, but these will be insufficient to present voters with the prospect of a viable alternative government. According to master electoral strategist and foremost proponent of a two-party system for Japan, People’s Life Party leader Ichiro Ozawa, what is necessary is to form a new party. Otherwise any policy agreement among opposition parties cannot be considered a completely united line. He is correct in arguing that ‘the people have to have an image of one party for it to be an option’. Currently the smaller parties are struggling to present a distinct policy profile to the electorate.

Those dissatisfied with the LDP and its performance in office (and there are many) will likely swell the ranks of non-voters rather than vote for any of the opposition parties. The polls clearly show that Abe’s decision to call the election is regarded unfavourably by a majority of voters.

For these reasons, then, the upcoming election should be seen as a mark of Abe’s political opportunism rather than a contest about substantive policy issues.

Aurelia George Mulgan is Professor at the University of New South Wales, Canberra.

This piece was originally published in the East Asia Forum. It is republished with permission.