What is Schengen?

The terrible terrorist attacks in Brussels in March have led to some confused reporting in the Australian media about Belgium’s and Europe’s “aggressive open-border policy”, and the implied link with terrorism. The border policy in Europe that is governed by the Schengen Acquis has sometimes been conflated with the immigration policies of Belgium and other European countries.

Some writers have drawn unfavourable parallels with Australian policy on these issues, though the basis for comparison, given geography, population and politics, is vanishingly small. A primer on the Schengen agreement might be useful.

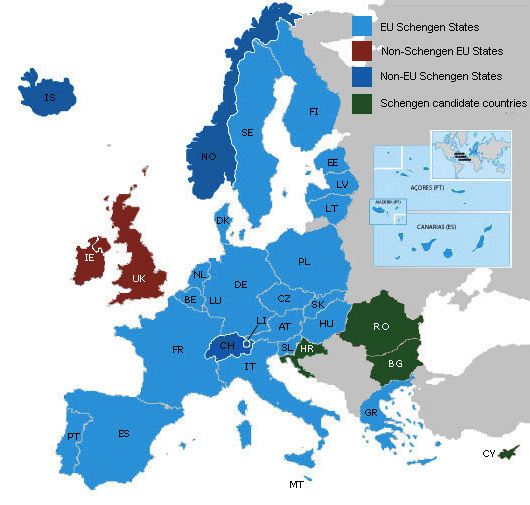

Belgium was indeed a pioneer of freedom of movement between neighbouring countries, having abolished internal border controls with its Benelux partners, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, in 1970. The Schengen agreement was signed in 1985 in the Luxembourg border village of that name, between the Benelux countries, Germany and France, and aimed at the gradual abolition of checks at their common borders. Since the first implementation of the Agreement in 1990, 22 of 28 European Union countries and four non-EU countries have joined the Schengen Area, and thus have a common policy in this regard.

The Schengen arrangements were integrated into the EU’s legal and institutional framework through the Treaty of Amsterdam, which came into effect in 1999. The United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland (two countries which share a common travel area), negotiated “opt-outs” from the Schengen Protocol to the Treaty, under terms enabling them to apply to opt back in, should they so wish. Countries joining the EU after Amsterdam could no longer seek such an opt-out.

The Schengen rules cover the following:

- regulation of how checks are carried out on people crossing the external borders of the EU, and the issuing of visas

- harmonisation of the conditions of entry and of the rules on visas for stays up to three months

- enhanced police cooperation (including rights of cross-border surveillance and hot pursuit)

- strengthened judicial cooperation through a faster extradition system and transfer of enforcement of criminal judgments, and

- the establishment of the Schengen Information System (SIS), which enables data sharing between member states.

The UK and Ireland have in fact opted in to police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters, and to the SIS. The Swiss cited the SIS as an important incentive to join Schengen in 2004, outweighing concerns about crime and illegal migration. The system has enjoyed some spectacular successes, such as the rapid extradition from Italy to the UK of London tube bomber Omar Hussein in 2005.

Schengen brings important economic benefits to Europe. It supports the free movement of people and goods in the European Union. It facilitates the intra-European €2.8 trillion annual cross-border trade. The single Schengen visa promotes tourism, and makes study and investment in the area more attractive. The lack of internal controls makes it easy to live in, say, France and work in Switzerland, and thousands of people do. Around 45 per cent of the workforce in Luxembourg resides in a different country. This ease of movement makes as much intuitive sense to ordinary people in the geographically small countries of continental Europe, or living in European border regions, as does free interstate travel in Australia to NSW residents who work in the ACT. There is also a direct saving through not staffing and maintaining multiple border crossings.

Increased migration into Europe, as well as major terrorist attacks, has brought the Schengen arrangements into the spotlight. Starting with France, following the November 2015 attack in Paris, several Schengen member countries have introduced temporary controls to part or all of their borders, permitted as a temporary measure under the 2006 Schengen code. The European Commission says that such measures should be “restricted to the bare minimum needed to respond to the threat in question.” It has asked Schengen members to find a coordinated approach and to lift controls by December 2016 at the latest.

These recent challenges have highlighted that the success of the internal freedom of Schengen relies on multiple factors: the successful policing of external borders of the Schengen area; strong cooperation between internal security services in the area; and adherence by all parties to EU law on relevant matters such as asylum seekers. It is clear that there are problems in all of these areas, but much less clear that a haphazard reintroduction of internal border controls would reduce the risk of terrorism. After all, so far as we know, the Brussels perpetrators were Belgian citizens. And major terrorist attacks are not a problem peculiar to Schengen countries.

Rebecca Fabrizi is Senior Strategic Research Fellow at the Centre for China in the World at the Australian National University. She has a background as a diplomat for both the UK and the European Union. This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence. It may be republished with attribution.