Zimbabwe's Soft Coup: The Road to Democracy?

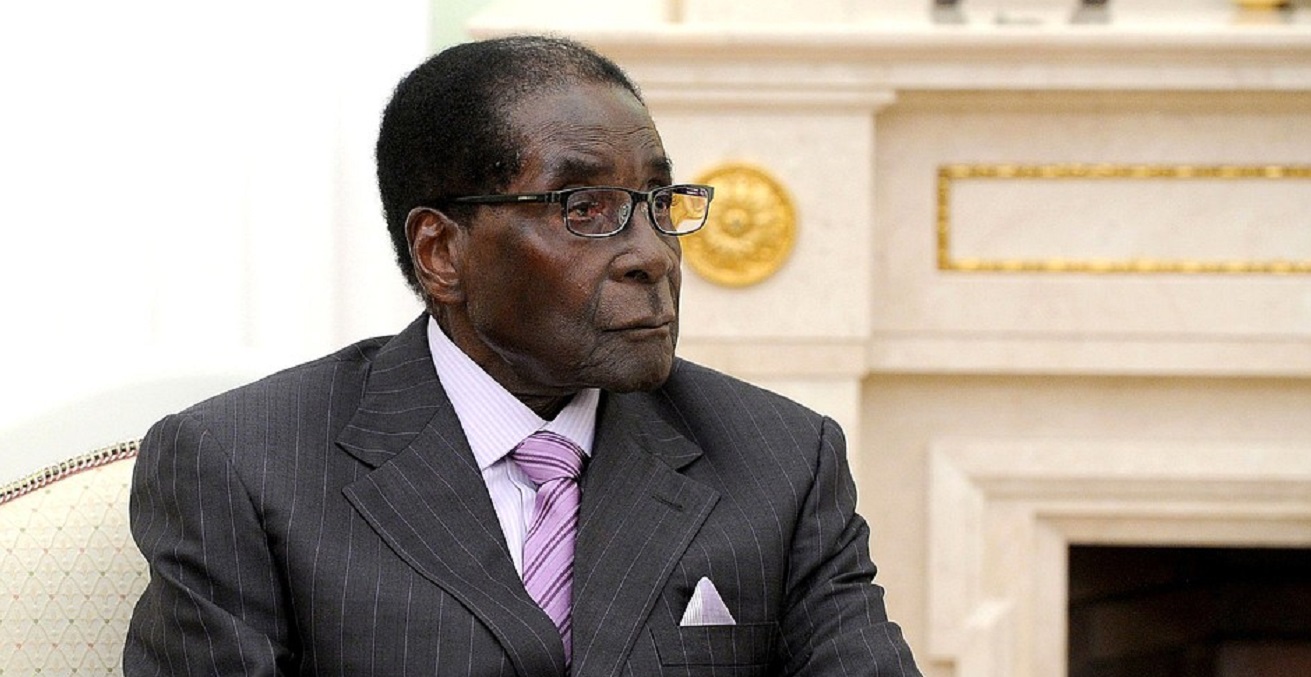

The looming end of Robert Mugabe’s rule presents the first real opportunity for change in how Zimbabwean government operates. What is it likely to mean?

What happened?

On Sunday 5 November President Robert Gabriel Mugabe dismissed his then Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa. Over the past couple of years bitter succession contests that pitted Mr Mugabe’s wife, Grace Mugabe, against Mnangagwa, entrenched deep divisions within the incumbent ZANU-PF government. Civilian and military rule have always been intertwined in post-independence Zimbabwe, which gained independence from Britain on 18 April 1980. As a former armed liberation movement, ZANU-PF’s continued hold on power has consistently depended on a well-organised security sector and the confidence of anti-colonial liberation war veterans.

Mnangagwa has overseen the country’s defence and security portfolios and been a close ally of veteran leader President Robert Mugabe over the years. However, the nonagenarian leader’s failing health, an unresolved succession issue, an ambitious but loyal deputy, and a determined wife with presidential aspirations created a rift between the war veterans and Robert Mugabe. In a miscalculated move by Grace Mugabe’s Generation 40 (G40) faction on 5 November, provincial councils and the ZANU-PF Youth League voted to have Emmerson Mnangagwa ousted as vice president. Robert Mugabe had earlier advised Mnangagwa to walk away from ZANU-PF at a Presidential Youth Interface Rally held in Bulawayo on 4 November. These strategic moves on the part of the G40 faction resulted in the military and Mnangagwa’s Lacoste (crocodile) faction launching a bloodless or soft coup to convince Mugabe to step down from power.

Initially, Zimbabweans were uneasy about the soft coup; would it be peaceful or bloody? Reassurances from the military that it continued to recognise Mugabe as the country’s president and chief commander of the defence forces saw Zimbabweans go about their day business-as-usual. Subsequent mediation efforts by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU) to ensure any leadership transition remained peaceful and constitutional led to a five-year transitional government of national unity (GNU) being tabled as a pre-conflict governance mechanism to ensure stability in the country. Mnangagwa was put forward as the top candidate to lead a post-Mugabe Zimbabwe alongside Joice Mujuru (another former vice president turned opposition leader) and long-time opposition stalwart, Morgan Tsvangirai.

As Mugabe had proved reluctant to step-down, a civil society march sanctioned by the military was scheduled to take place on 18 November. Thousands of Zimbabweans rallied behind a common cause to exert pressure for Mugabe to step down, many congratulating the military for its role in the apparent coup. Zimbabwe is setting a welcome precedent for what peaceful and non-contestational democratisation processes could potentially look like across the African continent.

Should the process turn violent, Mugabe’s 37-year-long grip on power would end rather unceremoniously in a country whose governance is maintained by a strategic liberation war narrative. However, viewing the GNU in transitional terms and as setting the groundwork for a future set of elections will be unsustainable. It will disincentivise the different parties to the agreement from working together to entrench people-centred governance in the country in the short and medium-terms.

Why do GNUs fail?

Governments of national unity are governance mechanisms whereby antagonistic political groups are required to cease contesting power and to jointly form a government. Over the past year I have written extensively on the need to pursue a GNU in lieu of elections as a way of ensuring stability and inclusive governance in Zimbabwe. My recent research, forthcoming in the Australasian Review of African Studies, demonstrates that liberal political systems—in the form of both single and multiparty governance structures—are inherently destabilising because of their underlying values of individualism and competition, and the zero-sum attitudes to political engagement that they incentivise. The global dominance of liberal institutions requires robust critiques of both the values that inform liberal procedures (e.g. electoral processes) and both incumbent and opposition political parties.

Liberal institutions prioritise contestation at the expense of political participation. Contestation is the struggle for political legitimacy, economic resources, power and knowledge. While no single group is capable of commanding complete legitimacy at any point in time, liberal institutions, including through electoral processes, assume that this is a possibility. On the other hand, political participation is people-centred and collaborative in nature. It involves the ongoing consultation and involvement of relevant stakeholders in the decision and policy-making, and agenda-setting activities of organisations responsible for policy development. The soft coup in Zimbabwe has created the necessary groundwork for a shift from the politics of political contestation to the politics of participation.

Contemporary approaches to peacebuilding tend to treat GNUs as temporary mechanisms to be superseded by multiparty political systems. This effectively undermines the realisation of prolonged and sustained peace in conflict settings by continuing to incentivise competitive and contestational forms of political engagement. Whereas Zimbabwe’s previous GNUs (including the most recent 2009-2013 one that was formed in the aftermath of widespread election-related violence) have been elite-centred, the broad support that Zimbabwean civil society demonstrated for the soft coup highlights that there is significant scope to make the new GNU formation people-centred.

What does the future hold for Zimbabweans?

Conceiving of GNUs in transitional terms—or as temporary mechanisms for the determination of the legislative framework for a multiparty system and electoral contestations of power—creates a disincentive for cooperation and collaboration. It encourages factionalism and top-down approaches to decision-making in the ‘post-conflict’ period. Limited mandates and the situation of GNUs within a broader liberal peacebuilding paradigm ultimately results in GNUs that prioritise oppositional politics, power contestation, competitive individualism and self-interested elite-bargaining.

Instead, GNUs should be conceived of as permanent fixtures and the appropriate bottom-up participatory mechanisms should be established to ensure accountability and to prevent initial GNU participants attending only to narrow constituent interests. That is, GNUs should be untethered from liberal peacebuilding imperatives and, more generally, the latter should be disavowed. GNUs therefore provide a blueprint for a non-liberal, deliberative-democratic political system.

Tinashe Jakwa is a conflict prevention and democratisation researcher at The University of Western Australia. Her paper, “Unsettling the liberal peace: More participation, less contestation” is forthcoming in the Australasian Review of African Studies (ARAS) in 2018.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.