You’re Fired: The Tillerson Edition

If Washington insiders are to be trusted, since at least mid-2017 it has been a question of when, not if, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson would be replaced. What stunned many this week was the manner of execution.

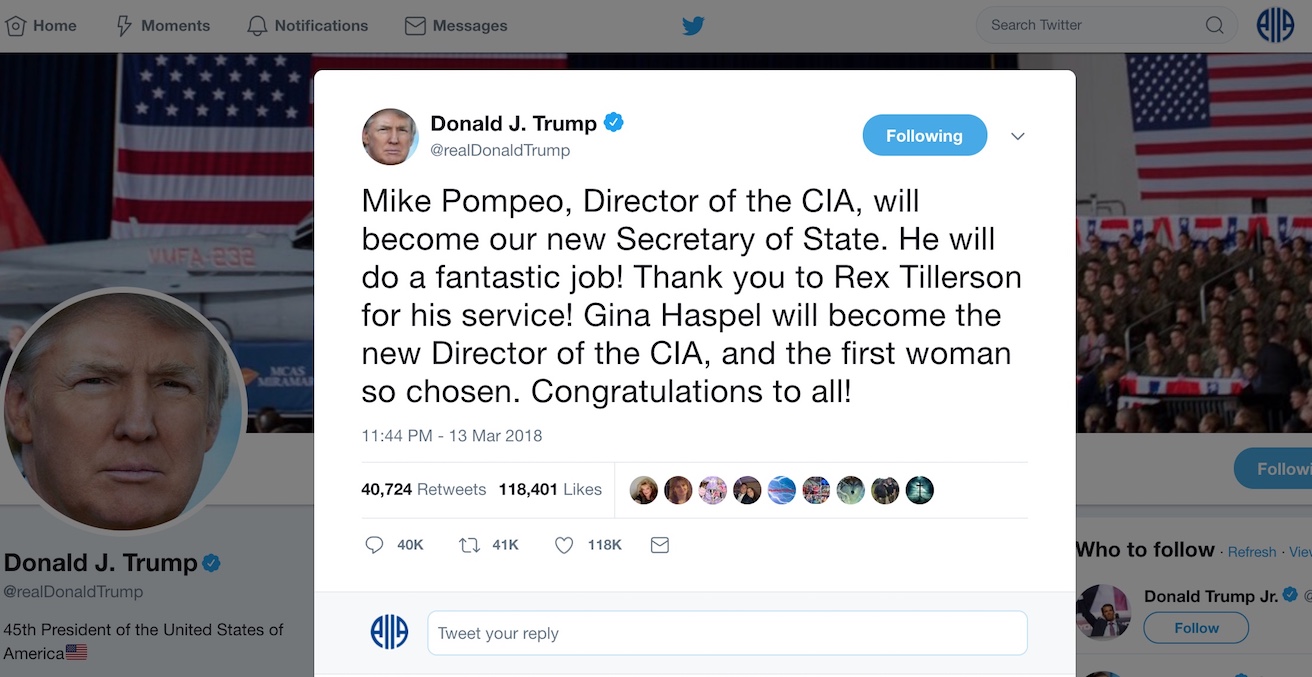

As far as human resources management practices go, firing someone via Twitter is on the list of methods that are most certainly unconventional and, given the gravitas of the particular post one has been dismissed from, rather unprofessional. Adding an extra layer of embarrassment is the fact that the person who was let go is not on the said social media platform, so apparently US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson found out he no longer enjoyed the president’s confidence by being shown the now infamous tweet hours before receiving an actual phone call from Donald Trump.

While we might pause to make sense of these developments and the way President Trump is interpreting his administrative power, it is also an apt time to reflect on the past 14 months of Rex Tillerson’s tenure at Foggy Bottom, where the Department of State is based. Practitioners and analysts from both ends of the political spectrum have already weighed in and deemed him one of the worst secretaries of state in US history.

The first-hand accounts and the hard evidence are unrelenting: US diplomacy has been weakened, questioned and sidelined. Some of it has been the secretary of state’s doing, while the rest has been circumstantial and reflective of the broader dynamics in the politics of US foreign policy-making.

By his own admission, Secretary Tillerson accepted the position of chief diplomat to oblige his wife. He didn’t exactly ooze the enthusiasm some of his predecessors had when they commenced their new roles. He also lacked the experience working in government, having spent all of his career in ExxonMobil climbing the corporate ladder all the way to CEO.

Nevertheless, an area in which he didn’t lack enthusiasm or experience, much to the displeasure of foreign service officers, was in restructuring the department. Granted, he was certainly not the first one to have tried making a complex bureaucracy like the State Department more effective and responsive. Yet, there is no recent record of a cabinet secretary who was as eager to see through 30 per cent budget cuts and claim to be determined to do more with less.

The looming slashing of resources would have been enough to undermine the morale of those working at State, however it has been coupled with the hollowing out of the department. Key positions at the undersecretary, assistant secretary and ambassador levels remain unfilled, and there has even been speculation that some of this has been deliberate as part of the restructuring strategy. Moreover, the string of resignations and retirements has been attributed directly to the decisions made at the top. Perhaps most worryingly, the recruitment of junior staff lags behind the record of previous administrations and it will inevitably leave a lasting imprint on the department’s capacity in the future.

Still, this suite of issues does not fully explain why the State has been left on the sidelines of foreign policy decision-making in the Trump administration. It is hardly a secret that the president and Secretary Tillerson have never really established a rapport that would have enabled the State Department to have a greater say in foreign policy debates. The two have been on the opposing sides of many burning issues: from North Korea to the Iran nuclear deal, Russia and climate change, to name just a few.

The practice of diplomacy as relationship-building is a long game that takes time to yield results: one that former Secretary of State George P. Shultz likened to gardening. In that, it is incompatible with the president’s ‘America First’ agenda of unilateralism, militarism and quick fixes. Yet often Secretary Tillerson acted in line with the said stances, as was seen in the recent decision to reform and defund the Department’s programs promoting human rights.

Among very few mitigating circumstances in assessing his track record, it has to be said that he has been up against deeper structural forces permeating the US foreign policy bureaucracy. It has been a long-observed trend that the centre of foreign policy-making has shifted away from the State Department towards a White House-centred system. The national security advisor and the national security council staff have been seizing power from the established bureaucracy. In recent decades, it has been more of an exception that the secretary of state was able to dominate and dictate foreign policy in the way of James Baker, Madeleine Albright or Hillary Clinton.

Finally, the designated secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, will be assuming the role with at least several fewer challenges than his predecessor. He is reported to have a good working relationship with President Trump, which has been built over the past year during Pompeo’s tenure at the helm of the CIA. He has also had previous government experience as a former congressman from Kansas. Most importantly, and perhaps most problematically, Pompeo shares Trump’s positions on the United States’ impending foreign policy challenges. Most of their preferred policy options go against diplomatic and multilateral solutions. If confirmed, the new secretary of state will undoubtedly be in a much better position credibly to speak for the president. However, the content he delivers might not be what the rest of the world wants to hear.

Dr Gorana Grgic is a jointly appointed lecturer at the US Studies Centre and the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.