World Toilet Day: Sanitation is a 4-Ply Issue

Achieving sanitation for all is not just about building more toilets. We also need to consider what people want to do and use, whether we are putting the lives and wellbeing of others at risk, and whether we are realistically calculating and off-setting the monetary costs involved.

The 19th of November is the biggest day in our professional calendar: World Toilet Day. Upon reading this, the normal reaction from the public is to laugh: why could we possibly need a day to celebrate and advocate for toilets?

The sanitary revolution is one of the greatest medical advances since 1840. Access to clean water and safely containing human excreta, together with antibiotics and vaccines, are believed to have doubled life expectancy in high income settings over the last 200 years. Yet 4.2 billion people – 55 percent of the global population – still don’t have access to a household toilet where their excreta is treated to ensure its potentially dangerous contents don’t come into contact with people, animals, or the environment – we refer to this as safely-managed sanitation.

It may shock you to hear that even in Australia, 24 percent of the population doesn’t have access to this level of sanitation service, which is likely a reflection of the inequities within this overall highly-resourced country, particularly for remote Indigenous communities. Nevertheless, Australia, alongside many other countries, has committed to achieve universal safely managed sanitation by 2030.

The need

In addition to increased mortality rates, poor sanitation contributes to stunting, recurrent episodes of diarrheal diseases, infections, and chronic malnutrition. Beyond these physical impacts, a lack of access to clean, private, and safe toilet facilities contributes to poorer mental and social wellbeing, increases the threat of gender-based violence and there is emerging evidence that poor sanitation is one reason why girls in lower- and middle-income countries drop out of school when they reach adolescence. This last point in particular often resonates with members of the Australian public – particularly women, parents, and trans- or gender-nonbinary persons – who regularly need to plan their public activities around the availability of suitable toilets. Too many have stories of needing to “go” but not being able to because the toilets don’t have doors that lock, are not well lit, don’t have a facility to dispose of sanitary products, or are gender exclusionary.

How to improve access to sanitation

The conventional approach to improving access to sanitation has historically been to build more toilets. However, this approach assumes people are too poor or don’t know how to build toilets, or that they don’t understand the health risks of open defecation, and has resulted in graveyards of unused toilets around the world.

Simply knowing that something is healthy for us is often not a sufficient motivator for us to behave in a certain way. That is why sanitation practitioners work hard to understand what people want in relation to sanitation, because using a safely managed toilet is always a better option than going behind a bush or in a back alley. In Australia, the movement toward providing different styles of toilets in public buildings shows that it is not only important that toilets safely contain excreta, but that they are designed to meet users’ needs.

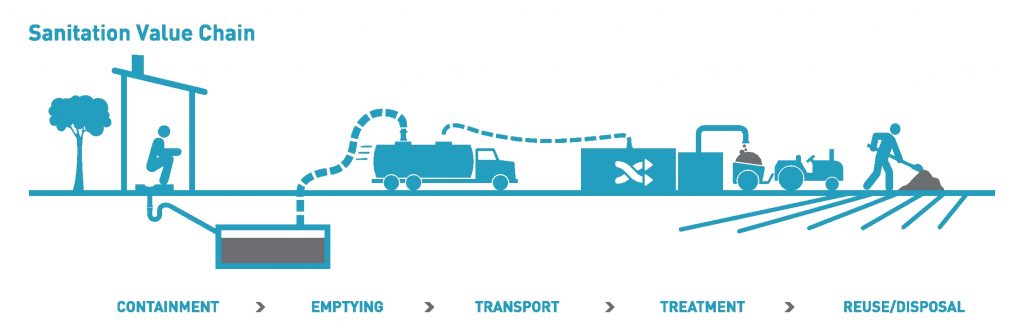

It isn’t just about toilets: the sanitation value chain in Australia

Toilets are the most familiar part of the sanitation value chain. The vast majority of Australians use one at least once a day. We rarely think about what happens next – we tend to flush and forget. But the contents of human excreta remain dangerous long after they leave our bodies. For the good of human physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and for the environment, it is essential that we carefully implement all of the steps of the sanitation value chain: contain excreta and either treat it immediately or transport it somewhere else to be treated, followed by appropriate reuse or disposal.

In Australia we typically contain, empty, and transport human excreta via a sewer network, or septic tanks with regular emptying and trucking. Wastewater treatment plants clean the incoming liquids and solids then dispose of treated water to the environment, and treated solids to landfill, or reuse treated water for irrigation, and treated solids as soil amendments.

The sanitation value chain on a global scale

There are around 3.5 billion people on the planet who have access to a toilet, but not one in their home and which includes a service to safely contain, treat, dispose of, or reuse their excreta after they’ve urinated, defecated, or menstruated.

In many parts of the world, it is either too expensive or not technically feasible to build sewered sanitation systems or septic tanks, so other ways of containing, emptying, and transporting excreta need to be considered. Unfortunately, this has often come at the expense of some people’s human rights. For example, members of the Dalit-caste in South Asia have historically removed “night soil” from non-flush toilets and pit latrines, typically at great risk to themselves, as often this was the only form of income generation available to them.

Although in many places the standards for pit-emptying have improved, this is by no means universal. A household may achieve “safely managed sanitation” by employing a pit-emptier, but discussion continues over how this may come at the expense of some of the world’s most vulnerable people. Furthermore, there is the challenge of finding a safe place for pit emptiers to dump the waste, which too often finds its way back into the environment without treatment.

Human excreta is an excellent source of nutrients and energy, meaning it can be reused as a fertiliser to produce animal feedstock, as a direct source of biomass energy, and to produce biogas. However, not everyone is comfortable with reusing human excreta, particularly as a fuel source for cooking or a medium for growing vegetables.

However unpopular they may be, the past decade has seen a concerted push for these reuse products to be financially valued. The argument has been that the cost of the sanitation value chain to residents could be offset by the sale of by-products of their excreta, often referred to as the circular economy for sanitation. However, cost recovery through such measures remains to be seen. A recent review indicated that there was limited evidence the circular economy for sanitation is financially viable. It is just too expensive – particularly for the world’s poorest people – for the sale of human excreta’s reusable by-products to fully offset the costs of containing, emptying, transporting, and treating it. Without subsidies for the most vulnerable, the circular economy for sanitation won’t achieve universal, safely managed sanitation.

Achieving sanitation for all is not just about building more toilets. It isn’t even about building more septic tanks, sewers, or treatment plants. The technology is no doubt important – it is what physically protects human health from the dangers lurking in our own, and others’, bowels. But we also need to ensure that along the sanitation value chain, we consider what people want to do and use, whether we are putting the lives and wellbeing of others at risk, and whether we are realistically calculating, and off-setting, the monetary costs involved.

Dani Barrington is a Lecturer in the School of Population and Global Health at The University of Western Australia. She uses participatory methods to understand people’s experiences and aspirations with regards to toilets, menstrual health and hygiene, incontinence, and water, with a focus on low-middle income contexts.

Naomi Francis is a Research Fellow at the Monash Sustainable Development Institute at Monash University. She has 10 years’ experience working as a researcher, engineer and educator in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), gender and community development, and Australian water management.