What Role can Women Play in Countering Violent Extremism?

In the wake of IS’ recent military defeats public attention has been trained on male combatants and attackers. The role of women has been consistently overlooked. It means the potential for women to lead efforts to counter future violent extremism is dangerously under appreciated.

Islamic State (IS) ideology long held that women should abstain from combat and instead fight from the confines of their homes. However, in October this year IS released a document that marked a change in tactical warfare with women called to arms:

It has become necessary for female Muslims to fulfil their duties on all fronts in supporting the mujahedeen in this battle.

This shift in ideology coincides with territorial losses and a diminishing number of male recruits. Not only has the demand for female combatants increased, but it appears some women now want to play a more active role within the organisation.

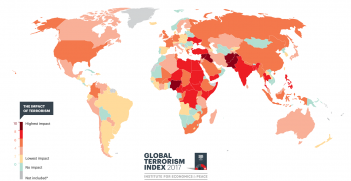

IS is the first jihadist group to have established a proto-state however, much like its predecessors, its potency is due to its ideological campaign. This means that despite significant attrition to its physical entity, IS is likely to continue to recruit and conduct attacks through its supporters in parts of the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Europe and North America through its brand of Islamist extremist ideology. The idea of the IS caliphate will long outlive the collapsed proto-state.

If IS will persist as a long-term ideological challenge, we need to understand its strategic and organisational structure; as women are an increasingly integral part of this structure, understanding their role is imperative.

In 2015, 40 Australian women were reported to have taken part in or supported terrorist activity in Syria, Iraq and Australia. Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop argued that it “defied all comprehension for women to support extremist groups such as Da’esh, given that it is women and girls who are disproportionately affected by the activities of terrorist groups.”

Many women are mistreated under Muslim (Shari’a) law and it is difficult to attribute autonomy to women when the IS ideology predominantly prescribes men to battle and women to their home and husbands. Women are to serve the men and produce more men. However, the worldwide increase in the number of female recruits and female-led attacks , in particular from Western nations like Australia, has fractured the narrative that portrays women only as victims.

The global crackdown on travel to Syria has contributed to an increase in female-led attacks in the recruits’ home countries. Women have recently been directly involved in terrorist attacks in Morocco, Kenya, France and Indonesia, and a recent report revealed women have been involved in nearly one in four Islamist plots across Europe in the first five months of 2017. While this figure is similar to that of the 22 per cent in 2016, it was 13 per cent and 5 per cent in 2014 and 2015 respectively.

Women are active as both facilitators and financiers of terrorism. They serve as intelligence sources, couriers, logistics suppliers, accountants, mentors, propagandists and international networkers. Some women have developed successful businesses and charities that serve to fund extremist causes.

The online presence of women is also strong. IS women manage the production and distribution of extremist propaganda and are predominantly responsible for recruitment. They extend information and support towards second-generation Muslims, Western converts, young and educated women from families with no tradition of jihad, women travelling with their husbands and those travelling alone. Foreign recruits experience different routes to radicalisation and are more inclined to reject traditional roles as mothers and teachers. Chat forums and online propaganda are tailored to address these recruits.

A female IS recruit recently wrote in Rumiyah, the IS propaganda magazine, that the time had come for women to:

Rise with courage and sacrifice in this war… not because of the small number of men but rather, due to their love for jihad.

Whether IS is encouraging women to commit attacks, or women no longer feel constrained by the rules of modesty and femininity, the language used by IS and the numbers of female recruits suggests a marked change in extremist practice.

Despite these changes, current techniques used for countering violent extremism (CVE) tend rely on the woman’s access to her family through the traditional roles of mother and wife. CVE has employed a conservatively gendered approach by using women to monitor, to detect and to report on radicalisation.

It fails to recognise that women can be much more than this. They can be effective mentors, intervention officers, educators, healthcare professionals, policy advisers and above all community activists. The expansion of their existing participation in these areas would greatly benefit CVE programs.

Women in communities vulnerable to the influence of violent extremism need to be viewed as potential community leaders. Their positive attributes and experiences in a life without extremism must be harnessed through education, training and opportunities to allow them to influence others.

In order to expand the role of women in CVE, it is critical to recognise the wide range of different roles, responsibilities and motivations of women in violent extremism. A simplified victim narrative hinders the capacity to deter and rehabilitate both women and men involved in IS and all future renditions of violent extremism.

Julia Bergin is a former intern at the Australian Institute of International Affairs, National Office. She is studying for a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.