Why I'd Vote for Donald Trump

Every decent person looks on goggle-eyed as Donald Trump continues his unlikely march to the Republican Party nomination. We are mesmerised by how he goes out of his way to flout every rule of “political correctness”, from calling Mexican immigrants “rapists” and flirting with the Ku Klux Klan, to dismissing women he does not like as fat and ugly.

As each primary comes and goes the words “President Trump” seem less like a joke and more like a possibility. For most in this country, and certainly among those who read The Conversation, that would be the worst outcome imaginable.

But Donald Trump in the Oval Office is not the worst outcome imaginable. Ted Cruz in the Oval Office is the worst outcome imaginable.

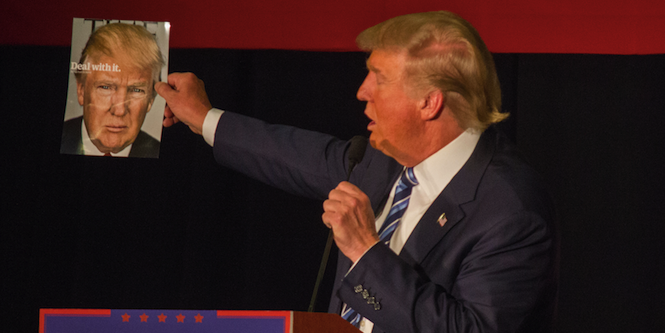

Trump is a showman. The kind of people drawn to him are the kind who watch The Apprentice, a piece of elaborate theatre in which Trump’s ritual bullying and humiliation make for good sport. As a politician he understands that the backlash against the cultural shifts of the 1960s and 1970s, shifts that continue today, always made a large portion of the American population uncomfortable and resentful.

So not only do his outrages appeal to those who are tired of having to suppress their social views, but the horror they cause among his opponents and in the mainstream media, reinforce the feeling among his supporters that here is a man who finally speaks for them.

What this means for Trump’s underlying politics, and the decisions he would make if he were president, is not at all obvious. Trump has a history of taking liberal stances on a range of issues, including favouring abortion rights, supporting a single-payer healthcare system and endorsing an amnesty for illegal immigrants.

He was a registered Democrat and friend of Hillary Clinton. It’s because of these positions that genuine political conservatives are deeply suspicious of him, calling Trump a “typical New York City liberal”.

Cruz’s rage

In contrast to Trump, Ted Cruz is a hard-line, Tea-Party style, evangelical warrior who would ruthlessly use the power of the presidency to impose his vision on America. Trump’s anger may be real, or more likely it’s part of his shtick, but Cruz is fuelled by the same deep rage that gave birth to the Tea Party.

The Texas senator has been one of the most uncompromising Republicans in a Senate notorious for its unwillingness to allow the government to govern. Socially he is among the most conservative of the new breed of right-wing Republicans. He opposes abortion in all cases, including rape (“it’s not the baby’s fault”), except when the mother’s life is endangered. He’s opposed not only to same-sex marriage, but to civil unions as well.

He believes that “the overwhelming majority of violent criminals are Democrats” and has lamented the fact that “non-believers” are allowed to vote. He gives succour to the conspiracy theory that President Obama banned military personnel from praying. (According to his evangelical parents the young Ted “gave his heart to Christ” at a youth camp when he was eight-years-old.)

Yes, Trump latched on the “birther” conspiracy, but it always seemed to be a calculated move.

Against Cruz’s record of fanaticism (whipping other Republicans to shut down the government by refusing it funding) Trump is, and sees himself as, a dealmaker. Cruz warned conservative voters not to be fooled: “[…] if you think Washington is fundamentally broken, then the answer is not to elect a dealmaker who will cut even more deals with Democrats and make the problem worse.”

I haven’t mentioned economic policy, foreign policy or climate change, but on each of them a Trump presidency is a less disconcerting prospect. And while President Cruz would surround himself with ideologues on a mission, Trump is likely to appoint some more sensible people.

I’m scared of Trump, a lot, but I’m terrified of Cruz. So if I found myself at the Republican Convention, due to convene in July to choose a presidential candidate, and the only choice was between Trump and Cruz, then “The Donald” would get my vote, no question.

Clive Hamilton is a Professor of Public Ethics in the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at Charles Sturt University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation on 6 March. It is republished with permission.