What next for Mosul?

After three years, Iraqi government forces have liberated Mosul from ISIS control. As the community begins to heal, it is Iraq’s female parliamentarians who are leading the efforts to rebuild.

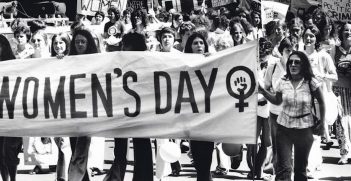

Following Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi’s declaration of victory over ISIS (Daesh) on 9 July, the important question is what comes next. The Iraqi government’s approach to rebuilding Mosul will provide crucial lessons for the broader Middle East region on peace-building, economic reconstruction, and social cohesion after conflict. While physically rebuilding Mosul’s infrastructure is a major task that lies ahead, the social fabric of the city, which suffered immensely under ISIS occupation and the military push to liberate the city, also requires rebuilding. To date, this conversation has been largely led by women.

Dr Farah Al-Saraj, a member of parliament in Iraq’s Nineveh province, recently visited Australia courtesy of the Australian government. I had the opportunity to interview her for an ARC Linkage project, ‘Towards Inclusive Peace’, on women’s post-conflict participation. Mosul, Nineveh’s capital, was the primary site of conflict between ISIS and Iraqi forces and coalition airstrikes, and it was the largest city in Iraq to fall to ISIS in 2014. In a context where the violence perpetrated against women has garnered attention both locally and internationally, women have sought to carve out a space in the aftermath of this conflict for their voices to be heard on what peacemaking entails.

Dr Al-Saraj has built an alliance of female parliamentarians in the Nineveh province, transcending political and ethnic divides, with the primary aim of facilitating the rebuilding and rehabilitation of her region. While it is difficult to understand the role that women have played in post-2003 Iraq, particularly within formal political institutions mired with issues like corruption, political gridlock and sectarian divisions, Dr Al-Saraj’s political experience provides an insight into how the parliamentary gender quota is empowering women, not only to participate in decisions about the ‘day after ISIS’, but also to lead them.

Roads to peace

In 2016, Dr Al-Saraj began a women parliamentarians’ initiative for the nine female parliamentarians in Nineveh province. The women come from different ethnic and religious backgrounds, but have found common ground in their discussions about Nineveh’s future post-ISIS. Given the context of violent sectarianism that has coloured Iraqi politics since 2003, this is no easy feat.

The work of Dr Al-Saraj and her colleagues highlights the possibility for the implementation of a local ‘women, peace and security’ agenda, and the significant roles that women can play in the post-conflict rebuilding of cities. According to Dr Al-Saraj, it is precisely her identity as a woman that enables her to carry out this work in Mosul by bringing authenticity to discussions about personal insecurity, violence and tragedies experienced by individuals and families in her city.

Dr Al-Saraj is in good company for this work; one of the other colleagues she named as being critical in this project is Vian Dakhil, the only Yazidi member of parliament in Iraq. Ms Dakhil has also been central in gaining international attention for the issues faced by the Yazidi community vis-à-vis ISIS, gaining the name ‘ISIS’s most wanted woman’.

Repairing the social fabric

The women parliamentarians have produced a set of recommendations for the Iraqi government focused on what they refer to as “community peace”. As Dr Al-Saraj explains, crimes committed by Daesh and their supporters are covered by Iraqi law, and those crimes need to be addressed within Iraq’s legal framework, although there are calls for broader action, like the push for the crimes against the Yazidi population to be classified as ‘genocide’. Her primary concern, and that of her colleagues, is addressing the needs of communities in Mosul that fall outside that framework.

The recommendations reiterate a commitment to enabling peaceful community relations, preventing vigilante justice and initiating a community peace process, much like truth and reconciliation commissions held in other countries such as South Africa. One key recommendation is to create a committee that is representative of the various groups in Nineveh to oversee the implementation of the proposed reconciliation processes. The ISIS governance system relied on people reporting neighbours, family and other community members for a variety of crimes, or for allegiance to the Iraqi government. This means that the proposed peace-building body in Mosul will have to work hard to address the damage sustained by the whole community as a result.

Women’s Participation

Nineveh’s female parliamentarians provide an interesting case of the roles women can and do play in Iraqi politics. The 25 per cent representative gender quota, enshrined in the 2005 constitution and the electoral laws that followed, has enabled women to win parliamentary seats. And while many dismiss the quota as electing women who toe the party line, Dr Al-Saraj and her colleagues show that this is patently not the case. So what remains as a barrier to women’s post-conflict participation and increasing their parliamentary representation beyond the 25 per cent threshold? According to Dr Al-Saraj, violence against political actors including women and the politicisation of peacebuilding efforts are major barriers.

Violence as a threat is a broad issue for all political actors, but particularly for those working in high-risk locations like Mosul. Iraqi women in particular have faced a devastating increase in gender-based violence, but the Iraqi population as a whole has faced political violence for a number of decades now and each blow lessens their trust in political processes. Dr Al-Saraj reiterates that the violence experienced is gender-specific, but not due only to her identity as a woman. She mentions that women hold leadership positions in Mosul’s society and she feels respected in her role as a parliamentarian. Women’s vulnerability to violence has been highlighted by the conflict in Mosul, but it is also important to dig deeper in trying to uncover how women in different parts of Iraq understand their insecurities as a barrier to political participation be it as a constituent or as a politician themselves.

Dr Al-Saraj also suggests that the embittered way upcoming elections have been playing out in Iraq could derail long-term reconstruction and rehabilitation plans, especially the momentum that initiatives like the one Nineveh’s parliamentarians have gained. It has essentially politicised their efforts.

So what role can women play in a post-ISIS Iraq? Female parliamentarians of Nineveh are not short of ideas or the political will to carry them out. Potentially, the kind of societal dialogue they have enabled provides a blueprint for other parts of Iraq or other actors in the Nineveh province on how to build social cohesion and how central women’s participation is in this post-conflict process for moving forward.

Yasmin Chilmeran is a PhD candidate at Monash University’s Gender Peace and Security Centre.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.