What China’s Involvement in Myanmar says about Asia’s Changing Regional Order

Beijing’s capability, willingness, and different concepts for peace-building are recentring the institutional architecture of Asia.

How is Asia’s regional order changing? In a new article in the Australian Journal of Politics and History, we argue that emerging security policy linkages between Northeast and Southeast Asian countries are reshaping the region. The regional architecture was never as simple as a US-centred “hub-and-spokes” system of alliances and partners. But today questions of order are proliferating with China’s rising assertiveness and uncertainty surrounding the Trump administration. Some states like Japan are defending regional order by cooperating on maritime security with partners like Vietnam and the Philippines. Australia is likewise coordinating policies to defend a rules-based order. Others such as South Korea are extending regional order by multilateralising capacity-building efforts in new functional areas such as cybersecurity. Most controversially, Beijing may be attempting to recentre the regional order by constructing new institutions and mechanisms with China at the centre.

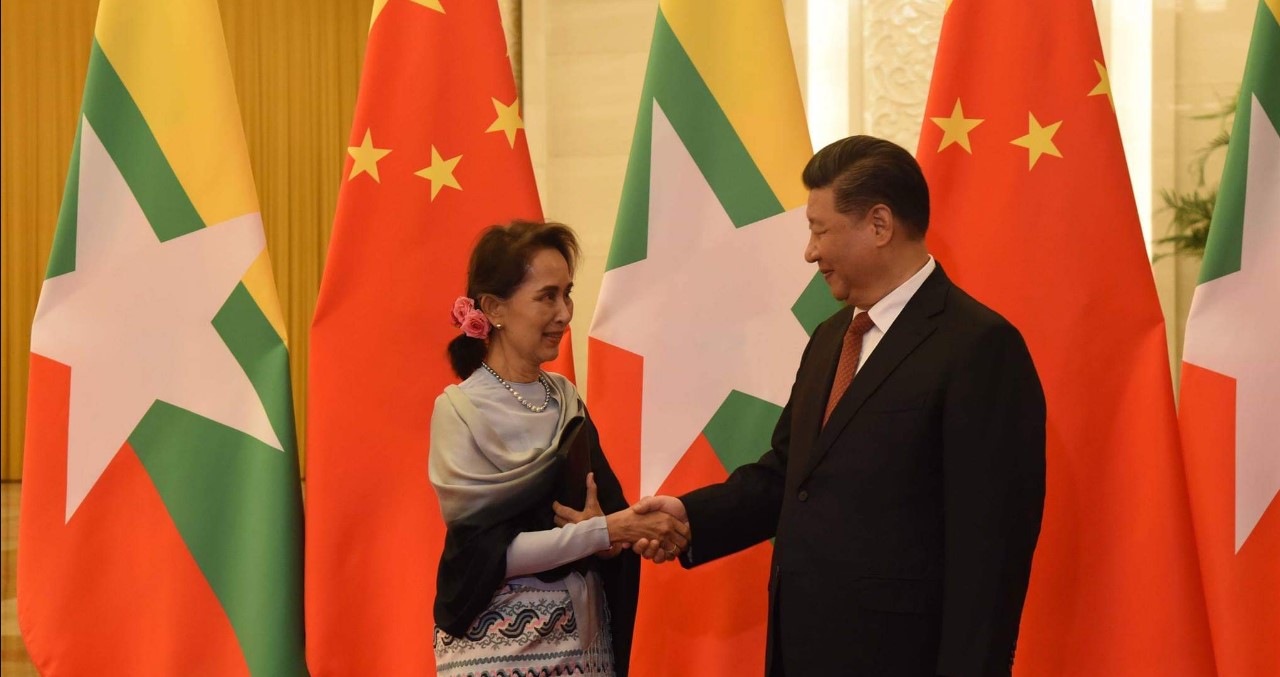

An illustrative case study is China’s peace-building role in Myanmar. China-Myanmar relations are important for Asia’s regional order in demonstrating how an increasingly capable and willing Beijing engages diplomatic and security challenges in its near abroad. China’s leaders prioritise economic development, before human rights or international law. They seek to increase political leverage via trade and investment and by becoming indispensable to multiple domestic stakeholders in a partner country. The geopolitical proximity and urgency of Myanmar’s security situation make it an early test of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and a leading indicator of a more assertive Beijing’s interaction with existing norms and institutions in the region.

Diplomatic ties between China and Myanmar extend back nearly seven decades. When Burma recognised the People’s Republic of China in 1950, it was one of the first non-communist entities to do so. Bilateral relations have since been referred to as pauk-phaw, or fraternal ties. After protests in 1988 and then a military coup in Burma, and after the Tiananmen Square Incident of 1989, pauk-phaw relations deepened because both countries faced diplomatic isolation, international criticism, and economic sanctions. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, China became an increasingly important investor for Myanmar. In 2011, the two countries issued a joint statement upgrading ties to a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership.”

Despite deepening relations, China maintains concerns for border security, owing to violence on the Myanmar side that periodically drives thousands to flee into China. Instability in areas controlled by armed ethnic groups in Myanmar also threaten Chinese economic interests, including investments in mining and major connectivity projects relevant to China’s energy security. As a result, Beijing has become more active in peace-building in Myanmar. China’s involvement in the complicated domestic politics of Myanmar also follows from shared ethnic and historical ties. Some sub-national groups in Myanmar, such as the Kokang, are largely Han Chinese, while others such as the Wa have historical links to communist insurgencies. The so-called “northern faction,” also including the Shan and Kachin groups, garners tacit Chinese support in negotiating with the Myanmar government and likely receives military and financial assistance from Beijing.

China’s peace-building activities include facilitating talks for the Kachin Independence Organisation and hosting dialogues in Ruili between the Kachin Independence Army and the Myanmar government. Since 2016, Beijing established closer relations with the opposition-turned-ruling-party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), and increased its peace-building efforts in Myanmar. In May 2017, Beijing assisted in mediating between the Myanmar central authorities and the Northern Alliance at the 21st Century Panglong Peace Conference. China has also hosted talks in Kunming, including among Myanmar’s Union Peace Commission and representatives of the Arakan Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army.

Myanmar identifies China as an attractive development partner because Beijing tends to separate economic engagement from human rights considerations, as seen in the extensive activities of Chinese state-owned enterprises and Yunnan-based traders. Western countries call for the United Nations to hold Myanmar’s military accountable for human rights violations. The World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and many international investors condition financial support on human rights improvements and associated political risks. In contrast to the criticisms of leading UN members and agencies about documented human rights violations, especially those against the Rohingya in Rakhine, Beijing has blocked Security Council action. Instead, China proposed a “three-stage plan” for paving the way for a cease-fire in Rakhine, encouraging bilateral exchanges between Myanmar and Bangladesh to deal with the refugee crisis, and increasing investment in the affected regions. This proposal was generally accepted by Myanmar.

Beijing offers an alternative economic development “order” with the BRI and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) where investment is meant to alleviate poverty and conflict in areas with ethnic insurgencies. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) is a major joint effort by the two governments under the BRI. The MOU on the CMEC Cooperation Plan (2019-2030) was signed by the governments at the Second Belt and Road Forum in April 2019 and reaffirmed Beijing’s commitment to alleviating ethnic tensions. China and Myanmar are setting up three core zones along their border to increase trade and logistics cooperation in areas that have experienced instability. The China-backed Muse-Mandalay railway is a bet on connectivity through regions of ongoing ethnic violence, and the Kyaukphyu port is to anchor a new special economic zone in Rakhine State.

China is also demonstrating strategic flexibility in adapting its policies toward Myanmar. After expanded economic relations produced political grievances in the country, including over high-profile projects such as the Shwe Gas pipeline and Myitsone Dam, China invested in more than 120 smaller projects. In addition to playing up the local benefits of such economic activity, China has initiated humanitarian programs such as the China-Myanmar Regional Centre for Major Disease Control and Prevention. China’s interests have expanded beyond its borders with trade, investment and people-people ties. Beijing’s willingness to transition from “non-interference” policies to the provision of “international public goods” has followed apace.

China’s peace-building efforts in Myanmar show how a major power can recentre regional order by promoting peace in unstable areas where the United States and United Nations have less of a presence. Although China’s peace-building agenda may not correlate with that of Western or even ASEAN countries, recentring the existing order is different from aggressively challenging or trying to replace it. By engaging in peace-building in Myanmar, Beijing is not necessarily looking to reshape the regional order in its own image or construct a parallel order. Instead, it is largely filling gaps left by other state actors and international organisations by adopting a flexible approach while protecting and promoting Chinese interests. Beijing’s capability and will to shift the centre of power and influence in Asia is changing institutional architecture with implications for the processes and products of policymaking in the region.

Leif-Eric Easley (PhD in Government, Harvard University) is Associate Professor of International Studies at Ewha University in Seoul. Associate Professor Easley’s publications can be viewed here.

Sea Young Kim (MA in Asian Studies, Georgetown University) is a Research Associate at the East Asia Institute in Seoul. Sea Young Kim’s profile can be viewed here.

This article is based on research presented in their co-authored publication, “New North-Southeast Asia Security Links: Defending, Recentring, and Extending Regional Order,” Australian Journal of Politics and History, Vol. 65, No. 3 (September 2019), pp. 377-394.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.