What Australia Can Learn from the Japan-China Summit

Working with China is a difficult diplomatic challenge for many countries, including Australia. The latest Japan-China Summit provides some ideas.

On 25 October Shinzo Abe paid an official visit to China, the first in seven years by a Japanese prime minister. China made efforts to be welcoming. Even the Global Times discouraged anti-Japan rhetoric. The latest joint Japanese-Chinese survey showed a positive trend with 42.2 percent of Chinese respondents saying they have “favorable” or “relatively favorable” impressions of Japan, up from 31.5 percent the year before.

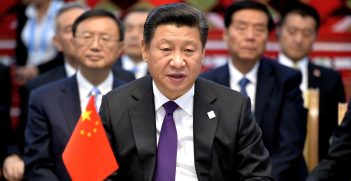

China’s warm welcome is in the context of current tensions in the US-China relationship. No matter what, Xi can’t lose face; hence, China can’t lose the ongoing trade war against the US. China needs to be ready to spend every political resource to push back against the US. Therefore, it would be unwise for China to antagonise Japan, the third largest economy and one of the US’ key allies.

Abe’s official visit was meaningful. It is noteworthy that it achieved more than 50 agreements, including an agreement to resume a currency swap deal for times of financial emergency. Yet, it is too early to say whether Abe’s visit was successful or not, since Chinese leaders mostly agreed to start talks as to what both nations can do rather than take specific actions to resolve bilateral issues, such as protection of intellectual property rights.

Abe has repeatedly made efforts with China to realise the East China Sea as “Sea of Peace”. In the past, and again this time, the issue of the East China Sea remains unresolved. The Japanese Government has raised the issue of China’s unilateral development of natural resources in the East China Sea.

However both leaders agreed to set up a hotline to avoid accidents in the East China Sea, and the first annual dialogue on this issue will be held within the year. These are positive outcomes. However, there will be pressure to achieve more; the Japanese public expects more than talks with Japanese media regularly reporting the number of Chinese Government-owned vessels entering the contiguous zone or intruding into the territorial sea surrounding the Senkaku Islands. Even on the day of Abe’s arrival in Beijing, four Chinese vessels were identified entering these waters.

China also failed to achieve consensus on some of its initiatives. On China’s signature grand strategy Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Japan decided to keep its distance even though Chinese leaders have repeatedly encouraged Japan to participate in construction associated with the BRI. According to Japanese media, despite Chinese Commerce Minister Zhong Shan announcing that Chinese and Japanese leaders had agreed to work together in third markets, Japanese Trade Minister Hiroshige Seko stressed at the post-meeting interview that such cooperation is not associated with the BRI.

So while the Japan-China relationship appears to be booming, especially in economic ties, the reality is not so significant as might be wished.

In terms of co-existing with China, what Australia and other countries could learn from Abe’s official visit to China this time are:

- China’s posture may not reflect its true intentions.

- It is hard to achieve tangible outcomes, but signing memoranda of understanding or agreeing to implement dialogues are still very important.

- Countries should not hesitate to raise their concerns with China, or otherwise China will interpret the situation to suit its convenience.

Soon Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison will meet with Chinese leaders. He should stay firm in dealing with his Chinese counterparts regardless of whether China presents a favorable or unfavorable posture. Granting compromises will simply allow China to take advantage in any future diplomatic negotiations. It is hard to get compromises from China; therefore, Morrison may be better to focus on securing national and regional interests while showing an openness to work together with China for regional prosperity.

Although Japanese experiences of working with the Middle Kingdom will not be the same as Australia’s, looking at their so-called “love-hate relationship” can give some ideas of working with China.

Yuichi Takatsuka is a former Japanese diplomat who was based in Canberra from 2015-18. He was also a visiting fellow at the Australia Centre on China in the World at The Australian National University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.