WannaCry? Lessons from this Week's Cyber Attacks

Australia seems to have avoided the worst of the latest global ransomware, WannaCry. The digital disruption, which some have linked to North Korea, is a reminder of the risks of increasing reliance on computers combined with complacency about cyber security.

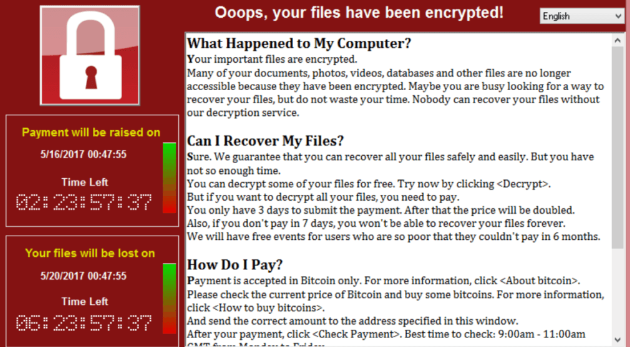

The ‘WannaCry’ cyber attack was first noticed on Friday 12 May and unfolded over the weekend. The attack involved a form of malware (malicious software) that entered computer networks, including those belonging to British hospitals, and encrypted computer data, thereby making the data unusable. Users were told that if they wanted to restore access to their files, they would need to pay a ransom of US$300 (AU$404) in bitcoins, hence the term, ‘ransomware’. Unless the ransom is paid, the ransomware deletes the computer’s files.

Bitcoins are an electronic currency. They potentially represent a whole new era of currency. Bitcoins dispense with the need for middle people (banks) as consumers deal directly and anonymously with each other. While bitcoins have been linked with criminal purchases (particularly of illegal drugs), they are growing in popularity and eventually may become mainstream. Ransomware victims who do not know how to purchase bitcoins are instructed by the cyber criminals. Because of this, there are far more ransomware victims each year than is commonly recognised: many victims just pay the ransom to get the files back as quickly as possible.

There are at least five implications to note. First, the WannaCry ransomware targeted Microsoft Windows XP operating systems. This is old software that Microsoft warned its customers would no longer receive security updates after April 2014. Unfortunately, those users who continued using the vulnerable systems have now paid the price for their penny pinching. To some extent, this attack has been self-inflicted: if the customers had upgraded their systems they could have avoided this attack. However, many attacks are yet to come from new malware.

Second, “only the paranoid survive”. This phrase comes from Andrew Grove (1936-2016), an information technology pioneer and early leader of the semiconductor giant, Intel. It is a good motto for the computer era. A cautious person can reduce their risk of becoming a victim of cyber crime with a few steps, including installing reputable antivirus software, frequently updating software, not clicking on unfamiliar links, never giving out their passwords, and not downloading email attachments from unknown senders.

Third, it is inevitable that there will be more instances of cyber crime. Ransomware is only the latest version of it. It is now harder to rob a bricks-and-mortar bank and so criminals have taken to robbing people via their computers and smart phones. Armed holdups were a localised form of crime; now a criminal can attack victims anywhere around the world.

Fourth, the scope for cyber crime will increase as we move towards the Internet of Things (IoT). This is a network of technologies that talk to each other without human interaction. A standard example is the ‘intelligent’ refrigerator that advises the ‘intelligent’ car that the household is running short of milk, so the car can advise the driver (via GPS navigation) where to buy milk on the way home.

IoT will provide many more opportunities for crime. One example is that a burglar could ‘listen’ to the devices talking to each other and detect whether the homeowner is at home. If not, the burglar could attack the house. A second example will be the rise of ‘car-jacking’ whereby hackers take control of a car remotely.

Fifth, crime has gone global but police forces have not. Most police forces have a local focus. Many police forces have only a limited role in national policing, let alone global policing. For example, an alleged criminal who flees from NSW into Victoria must be extradited back to NSW: NSW police cannot arrest the suspect outside NSW. This difficulty is pronounced when hackers based in one country commit crimes in others.

The headlong rush to make the most of new technology is proceeding faster than the voices of caution. While we may be seduced by the ease of modern computing, we must remain conscious of the risks and take steps to mitigate them.

Dr Keith Suter is managing director of the Global Directions think tank. Among his many roles, he is foreign affairs editor for Channel 7’s Sunrise program.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.