Vietnam's Refugees and the Slave Trade

The discovery of 39 dead Vietnamese in a lorry in Essex is part of a wider, global network of people-smuggling. This incident also demonstrates the changing motivations of refugees from Vietnam.

On 30 October 2019, 39 men and eight women were found suffocated to death in a refrigerated semi-trailer in Essex. Initially thought to be Chinese, the hopeful migrants were found to be Vietnamese looking for jobs in Britain. The semi-trailer was registered in the Black Sea port of Varna, Bulgaria, a stop-over on a well-established people-smuggling route between South East Asia and Europe. The Northern Irish driver and an accomplice were arrested on charges of manslaughter. More arrests will likely follow.

According to Benjamin Mueller in the New York Times on 1 November, these Vietnamese chose the “CO2 route,” paying exorbitant sums to unprincipled “snake-head” handlers to be transported from France into Britain after completing an almost 10,000 kilometre odyssey across Asia, which began in China where they obtained forged travel documents. To cross the Channel, they were locked in a refrigerated container with neither water, toilet nor ventilation, trusting they would be let out before asphyxiating. They were not.

According to UN statistics, Vietnamese and Albanians head the list of nationals from 130 countries trying to get into Britain as economic refugees. Why do they do it? I can’t comment about Albania, but Vietnam has made astonishing economic progress since devastating wars against the French and Americans between 1945 and 1975. Its population has grown from 45 to 92 million, achieving a per capita income of US $1,964 in 2018, at the lower end of middle-income countries.

This depressing story is not so much about refugees fleeing human rights violations by an overbearing communist government, but their hopes to improve living conditions for themselves and their families – a bigger home, more land, more material possessions. Their efforts are abetted by corrupt officials responsible for licensing migration brokers, local police turning a blind eye, and the promise of jobs and shelter from Vietnamese already settled in Britain. Some succeed, gaining well-paid employment and enjoying reasonable living conditions. Others find themselves grossly exploited, working long hours for little pay. The men sometimes find themselves in illegal cannabis growing operations, while the women work in Vietnamese-owned nail salons or the sex industry.

At the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, refugees were political. They included members of city-dwelling religious groups and traders fleeing the oppression they feared from a victorious communist government in Hanoi. Successive waves of desperate boat people braved the South China Sea, some of whom were picked up and repatriated to the US, Canada, Australia and France. Others, less fortunate, were attacked by pirates from Thailand or pushed back to sea by the Malaysian Navy.

Economic migration came later. It originated in Hai Phong, Quang Ninh and Ha Noi, northern provinces of the Red River Delta, and gradually spread south to the narrow mid-north panhandle provinces of Nghe An, Quang Binh and Ha Tinh. There, many tourist brochures create an outward appearance of rapid economic progress with luxury beach-front hotels and a burgeoning local handicrafts trade. But the brochures ignore the fact that many locals are under-employed and lived in poverty. Many also live with industrial pollution. In Ha Tinh province, the Formosa Steel Company established in the Vung Ang economic zone began discharging toxic waste into the local river around 2015 as it began steel production. When the fish died along the coast forty thousand people left the province in the first eight months of 2019, many seeking work abroad.

Two other push factors encouraged the diaspora of Vietnamese economic refugees. One followed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dismemberment of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s. Large numbers of Vietnamese guest workers in Russia and Soviet satellite states, particularly in East Germany, were suddenly isolated and impoverished. Some made it back to Vietnam, but others found jobs in the West, particularly in the United Kingdom. A second push factor was the global financial crisis of 2008 which left once-buoyant labour markets in a state of collapse. Again, many Vietnamese guest workers in Europe had to find jobs elsewhere, including Britain.

Given the increase in gross exploitation of Vietnamese economic migrants into Britain, it is incumbent on British authorities to end the trade, as well as the Vietnamese. How is it that a neighbouring Southeast Asian country such as the Philippines has been able to develop a code of conduct under its Filipino Migrant Workers’ legislation which is respected by host countries and helps prevent exploitation and slavery?

To answer the second question first, the Philippines has for decades had an orderly program allowing its workers to get jobs in foreign countries and remit their wages back home. They began after the Spanish-American War in 1898 in Hawaii, then migrated to service industries in the United States, and then as artists, musicians and construction workers in other countries in Asia and the Middle East. Many worked as crew members on ships. As a result, Filipinos were not seen as a threat by host countries, but as welcome workers who would not overstay their time and would respect orderly departure rules.

Vietnam has no such tradition. Indeed, since reunification in 1975, the Vietnamese government has largely turned a blind eye to economic refugees, considering them a bad reflection on the country’s socialist reconstruction programs. During the current decade the problem of migration to Britain became acute. In July 2015, Prime Minister David Cameron visited Hanoi to get help from officials. The then Home Secretary, Theresa May, introduced the Modern Slavery Act and established an Independent Anti-Slavery Commission (IASC) to combat the growth in the arrival of illegal foreign workers, particularly from Albania and Vietnam. So far, the success of British efforts has clearly been limited, although the latest tragedy might prompt Vietnamese authorities to do more. An AFP report from Hanoi on 5 November claims that authorities have already arrested eight people in connection with the 39 deaths. Nguyen Huu Cau, director of the Nghe An police, publicly characterised it as “a very painful humanitarian accident.”

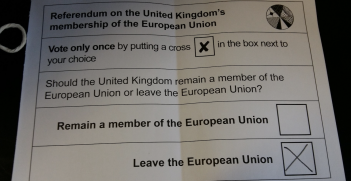

Will Hanoi now use its considerable authoritative powers to stamp out the local corruption that allows its workers to try to reach European labour markets at the mercy of ruthless snake head agents? Can the British assist them to solve what has become a substantial humanitarian problem? The advent of Brexit is unlikely to make conditions for illegal immigrants easier.

Richard Broinowski AO was the Australian Ambassador to Vietnam from 1983 to 1985. He is the immediate past president of AIIA NSW and a frequent commentator on public affairs on radio and television. He served in the Australian Embassy in Tehran as First Secretary in 1971-73 and was later Australian Ambassador to the Republic of Korea, Central American Republics and Cuba, and General Manager of Radio Australia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.