US-Australia-Indonesia Trilateral Security? Conditions for Cooperation

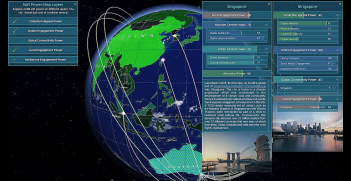

Since the 1950s, US strategic architecture in the Indo-Pacific has been premised on its hubs-and-spokes model of bilateral alliances and security partnerships. Since the 2000s the US began working toward forging deeper interrelationships between its regional allies and partners.

The emerging strategy ultimately aims to interlink long-standing allies like Japan and Australia, and also non-traditional partners in the development of a security network capable of maintaining the regional “rules-based order.” In analysing the US-led triangular Indo-Pacific geometry, this article considers the prospects of an evolving and substantive US–Australia–Indonesia security trilateral.

It does so by utilising JDB Miller’s “conditions for cooperation framework” to test the likelihood of greater cooperation between these three states. These conditions include cultural similarity, economic equality, habits of international association, the perception of common danger, and greater power pressure.

Cultural Similarity

For Miller, the cultural connection, the stated language, history, social systems and values, between states unlocks a pathway to cooperation, or at least averts a potential obstacle.

In terms of the similarities between their respective societies, Indonesia is a clear outlier, although the differences between elites in the three states and their societies at large are considerably smaller. The notion of consensual respect, and its colloquial manifestation of “saving face,” though, are often at odds with the results orientation of Western states, the US in particular. This is particularly visible in American and to a lesser extent Australian, reticence toward ASEAN where the relationship and the process is often valued over getting things done.

Economic Equality

This condition is a central component for effective security cooperation, and as Miller argues there needs to exist some economic parity or equity in a prospective contribution to a joint operation between the states concerned. It is important that there can be an “equality of sacrifice.”

If, as explained earlier, US strategy is to develop principled security networks in Asia, then Indonesia’s (as well as Australia’s) location can also be considered a tangible source of power. The region of operation is critical to comprehending the power equality calculus in this condition. Moreover, in part the realisation of any trilateral security arrangement is a function of complementarities not identical contributions. While on the face of it, Indonesia and Australia are comparable middle powers, Indonesia’s capabilities to contribute to a prospective US-led military operation in the Indo-Pacific should it opt to do so, are considerably limited. Clearly Indonesia differs markedly from Australia, which is deeply enmeshed in the US alliance structure and has a proven high level of interoperability with American expeditionary forces.

Habits of Association

Indonesia’s future political and military associations will be strongly shaped by its strategic culture. As Yohanes Sulaiman points out, Indonesia’s international behaviour is strongly influenced by the legacy of its struggle for independence, which has left Indonesian policymakers with a strong sense of vulnerability and its military with a primarily internal and defensive outlook.

For Western policymakers, Sulaiman concludes that, while Indonesia “does welcome defense cooperation, it does not want to be engaged in military alliances and pacts for fear of losing its independence.” Further, he argues that Indonesia will rebuff any efforts “to involve [it] in broader regional efforts to counter Chinese assertiveness”. Indonesia’s strategic culture is starkly different from the ANZUS partners and puts strict limitations on the prospects for any formalised alignment.

As such, although their historical experiences differ significantly, in an increasingly uncertain regional security context Indonesia may now be set to consider low-level cooperation that is predisposed to capacity building in counterterrorism and maritime awareness. Such associations speak to Indonesia’s domestic security challenges and by initiating cooperation at low-levels, it allows for a gradualist and not a disruptive challenge to the values of Indonesia’s strategic culture.

Sense of Common Danger

National perceptions of China are heavily contextualised by broader threat perceptions. Indonesia is on the frontline of Chinese expansionism and shares a contested border in the Natuna Sea’s overlap with China’s southern South China Sea (SCS) claims. Naval and or Coast Guard clashes have occurred in this area as recently as 2016.

Although Indonesia does not acknowledge maritime delimitation issues with China, arguably its statement announcing the presence of the North Natuna Sea map attests to its concerns regarding any questions as to the overlap of its EEZ and continental shelf with China’s southern most extension of its SCS claims. In these delimitation statements, we can see that Indonesia shares with the US and Australia a preference for the regional status quo, from which it has benefitted greatly.

While for the United States and Australia, situated in the eastern and south-western Pacific respectively, despite the prospect of chronic and substantive effects, they are not faced with the same acute costs as Indonesia. Similarly, the increasing interoperability of the US and Japan alliance, and so too with Australia, provide them with “a power aggregation effect” in defence of their interests from Chinese influences.

Where there exists increasing convergence of threat perceptions is in the transnational security domain, in particular on the rise of Jihadist terrorism and its intersection with maritime security.

With estimates of Southeast Asian foreign fighters operating in Iraq and Syria numbering around 600 and some of these expected to return home, the threat amplifies. But it amplifies not just for Indonesia but also for Australia and the US. Clearly, in this space, the possibility exists for these three states to engage in human and infrastructure capacity building in intelligence gathering, maritime surveillance, and policing.

Greater Power Pressure

Greater power pressure is understood by Miller to be manifested either overtly or covertly and in a myriad of ways including that of military, political, and/or economic pressure.

In this case study, it is evident that both Australia and Indonesia are “subject to the homogenising impact of global forces, still largely emanating from the United States” which curtail some of the sharpness of the cultural divide. For foreign policy practitioners this effect is even more pronounced as their epistemic environments generally reinforce beliefs about the benefits of US hegemony.

Nonetheless, in his analysis, Miller seemingly ascribes the least import to this condition. And in both the Miller and the Taylor and Ball analyses, the US was viewed to exercise its power in a less direct and more subtle fashion.

For the US, any US–Indonesia–Australia trilateral would be a longer-term prospect, but one where Australia as a proximal neighbour and with a sound history of successful cooperation in the bilateral CT policing space might cautiously and patiently work toward developing a closer three-way relationship.

So, while US endeavours to maintain its regional primacy and its military continues to shore up security relationships with allies and partners, Australia may now be the preferred initiator of any moves toward low-level trilateral discussions, which, in the historical context, may have the added benefit of being more palatable for Indonesia’s foreign policy makers.

Conclusion

Though the prospective trilateral may endear itself to strategic planners in Washington, its prospects, for the most part, remain strictly limited into the near future. Despite historical comfort with the regional status quo, propping up the US-led “rules-based order” in the Indo-Pacific is not commensurate with Indonesia’s long-held strategic thinking.

As we have identified, Indonesia’s limited maritime security capabilities hamper its goals to maintain strategic autonomy and territorial sovereignty against the backdrop of an increasingly deteriorating regional security environment. In rectifying this concern, Jakarta looks to external powers for support in developing its maritime space. Despite misgivings over past tensions, these technologically capable partners include the US and Australia.

Extending security cooperation to Indonesia will then be most feasible in areas of mutual interest that are strictly “sub-strategic”, non-traditional issues such as countering terrorism, piracy, people smuggling and IUU fishing.

American and Australian interests in defending a “rules-based order” in the Indo-Pacific through the development of a principled security network including states like Indonesia, appear then to be relegated to low order issues addressing transnational crime. However, a clear spill over effect exists between upgrading Indonesia’s maritime surveillance capabilities and upholding the principles of the current order.

Any prospective trilateral cooperation in this area also has the benefit of providing the ANZUS partners with a clearer operating picture of the southern littoral of the South China Sea and the important maritime thoroughfares between the Pacific and Indian oceans. But more importantly, it provides Jakarta with a greater picture of security concerns within its own maritime space, which may in itself muster greater political will to resist China’s maritime expansion.

However, this is attendant on Indonesia’s self-realisation of the threat and not it being ascribed from Washington or Canberra. As Ann Marie Murphy puts it “A potential danger for the US–Indonesian partnership is that Washington will make too strong a push for Indonesia to adopt a confrontational stance toward China before Indonesian officials have concluded independently that such a shift is in their national interests.”

Recognition of these limits will be crucial to the effectiveness of any efforts to include Indonesia into any new Indo-Pacific geometry.

Maryanne Kelton is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations in the College of Business Government and Law at Flinders University in Adelaide. Her research interests include Australia-US alliance relations, Australian foreign policy, economic statecraft, cyber enabled interference campaigns, and trust in international relations.

David Willis is a PhD candidate in international relations in the College of Business, Government and Law at Flinders University in Adelaide. His research interests are in the emerging geopolitical and technological challenges to Australia, with a focus on Indonesia. David is completing his thesis on explanations of Indonesia’s foreign policy alignment.

This article is an extract from Clarke’s article in Volume 73, Issue 3 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled “US-Australia-Indonesia Trilateral Security? Conditions for Cooperation.” It is republished with permission.