Uruguay's Victory Over Big Tobacco

Uruguay’s tough tobacco packaging-control measures were vindicated last month when a tribunal at the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes dismissed claims brought by Philip Morris. It followed defeats for Big Tobacco related to similar legislation in Australia and the UK; but the Uruguay decision stands out as a pivotal victory for a sovereign’s right to regulate in the interests of public welfare and as a significant test of investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms.

Uruguay has the third highest smoking rate in Latin America, responsible for 15 per cent of all deaths of adults over the age of 30, against a global average of 12 per cent. The economic impact of tobacco consumption is equally grave with an estimated US$150 million per year in tobacco-related health spending. In an attempt to counter these facts, Uruguay has taken a range of increasingly stringent regulatory measures for tobacco control since 2000.

Triggers to the dispute

Philip Morris’ Swiss and Uruguayan entities brought a claim against Uruguay alleging various breaches of the Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) as a result of two of the regulatory measures. The company claimed that the measures had forced it to withdraw seven of its brands from the Uruguay market, substantially affecting the value of Abal Hermanos S.A. (Abal), Philip Morris’ wholly owned Uruguayan subsidiary.

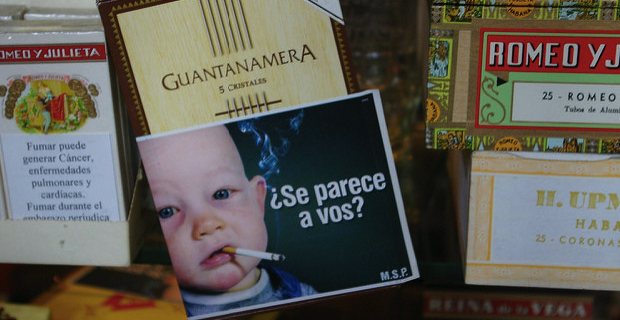

The two regulatory measures that gave rise to this dispute were the Single Presentation Requirement (SPR) which mandated that each brand of tobacco products is to have a single presentation, forbidding more than one variant of cigarette per brand, and the 80/80 Regulation, mandating an increase in the size of graphic pictorial health warnings on both sides of the cigarette pack from 50 per cent to 80 per cent of the surface area. The measures were enacted in an effort to warn consumers about the health effects of smoking and to prevent consumers from being misled by variations in branding and into believing that some cigarette variants were less harmful than others.

Big tobacco’s arguments

There were four substantive allegations of breach of the BIT and one additional allegation of a denial of justice during the Philip Morris legal challenge to the measures in Uruguay’s domestic legal system. First, that the measures constituted indirect expropriation of seven of Abal’s thirteen variants, including the goodwill and legal rights deriving from the associated intellectual property, in breach of the BIT. Secondly, that Uruguay had denied the claimants fair and equitable treatment (FET) in breach of the BIT. Thirdly, that Uruguay had impaired the use and enjoyment of the claimants investments and fourthly, that Uruguay had failed to observe commitments as to the use of trademarks.

The tribunal by majority dismissed all of these claims, and made important findings especially in relation to the first two arguments, which will be the focus of this article. There was a partial dissent in this decision by arbitrator Gary Born, highlighting the doctrinal uncertainties that remain in relation to the FET standard of review by investment tribunals.

Tribunal decision

The tribunal dismissed the expropriation claim for several reasons. First, it determined that there was not even a prima facie case of indirect expropriation in relation to the 80/80 Regulation, as the brand and other distinctive elements continued to appear on cigarette packs. In relation to the SPR, the effect of the measures had to be considered on Abal’s business as a whole, which it noted actually grew in profitability from 2011 onwards. The tribunal then went on to consider a state’s police power under customary international law. A state’s police power is its power to regulate in maintenance of public order and welfare.

The BIT had to be interpreted in accordance with the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which requires that treaty provisions be interpreted in light of relevant rules of international law, a reference that includes customary international law. The tribunal noted that a trend differentiating the exercise of police powers from indirect expropriation emerged after 2000, when a range of decisions developed the scope, content and conditions of the state’s police powers doctrine, anchoring it in international law. Besides investment tribunal decisions, the doctrine has been recognised by other authoritative sources such as the OECD.

The tribunal stressed that the SPR and 80/80 Regulation had been adopted in fulfilment of Uruguay’s national and international legal obligations for the protection of public health. The tribunal stated that it will be a valid exercise of a state’s police power and will not constitute indirect expropriation if a state’s action is taken bona fide for the purpose of protecting public welfare, is non-discriminatory and proportionate. The challenged measures had met these conditions.

The claimants also argued that the challenged measures amounted to a denial of FET in breach of treaty protections alleging that the measures were arbitrary, adopted without scientific evidence, without due consideration by public officials and with no reasonable connection between the objectives of the state and the utility of the measures. The SPR was criticised as unprecedented and not a part of recommended tobacco control measures. The tribunal ultimately held that both measures had been implemented for the purpose of protecting public health, and found there was a connection between the objective pursued by the state and the utility of the measures, as supported by the amicus curiae briefs filed by the World Health Organization (WHO) with the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Secretariat, and by the Pan American Health Organization. The tribunal held there was enough supporting evidence available at an international level on which Uruguay could rely.

The tribunal then applied European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence, finding that regulatory authorities have a margin of appreciation, or the ability to adapt laws to suit individual jurisdictions, when making public policy determinations. The tribunal held “(t)he responsibility for public health measures rests with the government and investment tribunals should pay great deference to governmental judgments of national needs in matters such as the protection of public health.”

Comment

This is a significant decision which will be referenced in investment jurisprudence for years to come. It further solidifies the role of police powers, when validly exercised, in exempting a state from having to compensate an investor. Controversy will remain about a state’s margin of appreciation in the way they implement policy in circumstances where there is no textual basis in a BIT to support such latitudes. The margin of appreciation will no doubt be a battleground yet in future disputes.

The decision should quiet those worried that investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms in investment treaties erode state sovereignty, but will conversely be concerning to large corporate investors about regulatory uncertainty. On a policy level, the decision paves the way for more states to introduce stricter tobacco control measures, with several having done so already. Philip Morris now has its answer on the merits of plain packaging—something it said that it was deprived of when, in a similar dispute involving Australia, a differently constituted tribunal found an abuse of process by Philip Morris in bringing the claim and declined jurisdiction.

Marina Kofman is a lawyer specialising in international law and international arbitration. She is the dispute resolution case manager at the Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration and the vice chair of the NSW Young Lawyers International Law Committee.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with permission.