The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: 70 Years On

Seventy years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted, significant work is still needed to realise its vision.

On 10 December we celebrate the 70th Anniversary of the adoption by the UN General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a document which set out a new direction for humanity.

Let us go back to 1948; this was not the best year for human rights.

It was the year of the Berlin blockade by the Soviet army which started on 24 June and ended almost one year later. The Stalinisation of Eastern Europe was about to accelerate in countries forcefully incorporated into the Soviet Empire. Apartheid laws were introduced in South Africa, and much of the world remained under a colonial system.

Why in such an inhospitable time for human rights was the UDHR born? There are at least two possible answers.

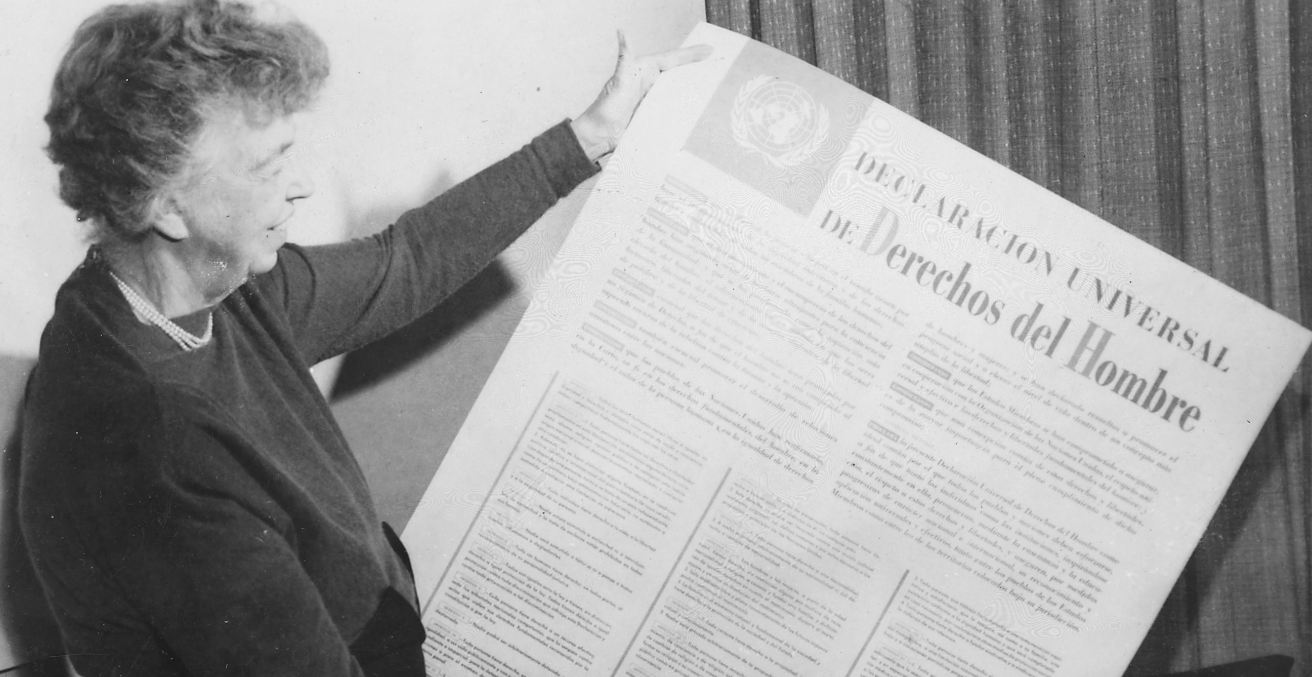

The first is the power of leadership at the time of Eleanor Roosevelt and of the USA, which was seen then as the world’s moral leader. Mrs Roosevelt, with Canadian and French support, was the principal drafter; important contributions were made by people from Chile, China, Lebanon and the USSR. Only South Africa was fundamentally opposed to the declaration.

Second, the genesis of UDHR was rooted in the human rights abuses of World War II in which tens of millions died across the world. Particularly abhorrent was the Nazi holocaust and the concentration camps. The general feeling of “never again” compelled us to build a world order that would prevent a repeat of these atrocities. So in February 1947 the Commission on Human Rights was appointed by the UN to create an “international bill of rights” to apply to every human being regardless of such characteristics as sex, race and religion.

Reaching agreement on the contents of the document was not easy. Member states voted more than 1,400 times on practically every clause of the text. The USSR would not accept the inclusion of freedom of expression and other civil liberties; some Islamic states objected to the articles on equal marriage rights and on the right to change religious belief; and several Western countries criticised the commitment to economic, social and cultural rights, seeing them as an introduction of socialism by stealth.

The Universal Declaration

Finally, on 10 December 1948 the UN General Assembly voted in favour of the Universal Declaration: 48 in favour, eight abstentions and zero against. The United Nations recognised that the “inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”. The Declaration was a visionary document: a triumph of hope and optimism. It was the first global statement of universal human rights standards, which we now take for granted. Article 1 proclaimed that “Everyone is born free and equal in dignity and with rights”.

The 30 articles of the UDHR set out in unprecedented detail the standards of dignity, respect and justice to which everyone is entitled because they are human. The Declaration focuses on individual rights and enumerates political and civil rights and social, economic and cultural rights. Article 29 emphasises the duty of the entire international community to create a society that allows for the full realisation of human rights.

Although the Declaration is not binding on states, by now it forms part of customary international law although its educational power exceeds its legal effect.

Since 1948, many advances in human rights have improved the lives of millions of people: such as the end of apartheid and the growth of democracy in Latin America and Eastern Europe and, more recently, economic and social development in Asia. The international community has developed an international human rights law system with clearly defined human rights standards.

Seventy years later, the Universal Declaration continues to be the inspiration behind a global movement, while setting the benchmark for the world to attain and providing a standard against which we can all be judged.

Human rights in a contemporary world

But much is yet to be achieved. We witness human rights violations associated with the mass arrival of refugees and migrants, Islamic radicalisation and terrorism, inter-cultural conflicts, economic inequality and a range of other ills. We witness the global instability of superpower realignment and the rise of authoritarian leaders and populism.

This year Freedom House, the Washington-based NGO that has monitored global freedom since 1941, reported that around the world, political and civil rights sank to their lowest level for a decade. Even nations that pride themselves on a deep democratic history are slipping on the scale, as trust in institutions is eroded and checks and balances slip out of equilibrium. For example, the United States fell to 86 out of 100 on a scale measuring a wide range of political and individual rights and the rule of law, and the United Kingdom slipped to 94. This trend is a matter of real concern and gives us a call to action.

Human rights in Australia

There is also much we can do in Australia. Australia is the only developed country without significant constitutional protections of civil liberties or a statutory bill of rights. Currently, the Australian Parliament can legislate for apartheid-style laws and the High Court could uphold them as agreeing with the Constitution.

There are many other human rights issues that could be improved upon. For example, economic and social rights of Indigenous Australians require massive attention. Violence against women remains at significant levels. Anti-terrorist laws need to ensure both a proportional response to a threat and protection of civil liberties. Further changes are required to make Australia’s immigration laws and practices compliant with international human rights standards.

All these changes are easily achievable with better leadership. We need leadership of the quality and vision provided by Eleanor Roosevelt during her work on the Universal Declaration.

Human rights education

Much more needs to be done to promote human rights culture worldwide. Australia, for example, needs to give a higher priority to human rights education. Culture regarding human rights is not automatically acquired. Human rights standards need to be learned by each generation and transferred to the next.

The UDHR, its history and the principles it exposes provide good focus for such education. The promotion of human rights culture is of special importance in diverse societies like Australia, as human rights provide an internationally recognised set of secular standards that apply to all peoples regardless of their culture, religion, gender or any other characteristic. Domestic bills of rights usually have a strong educational value, too.

And let us remember, that human rights education is not about preserving the status quo but about advancing a just and better society. The UDHR remains the best conceptual tool to oppose populism, nationalism, chauvinism and isolationism.

The ultimate test of a nation’s commitment to human rights as a nation is, however, not what we aspire to, nor the conventions we sign and not even the laws that we set in place. Rather it is how we treat our most vulnerable and powerless. Human rights promote human dignity, justice and freedoms. They are the vehicle that enables people to flourish without fear, intimidation or persecution.

Professor Sev Ozdowski AM is Director, Equity and Diversity at Western Sydney University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.