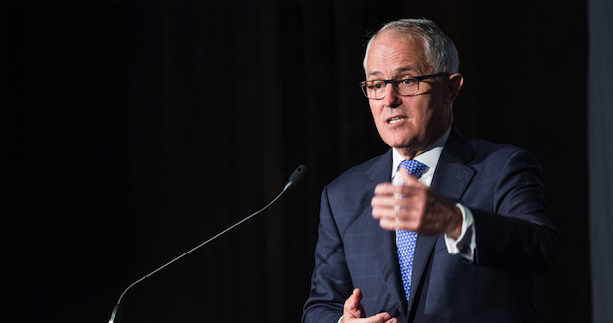

Turnbull's Foreign Policy: ‘Continuity with Change’

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s address to the Lowy Institute on 23 March offers an important opportunity to assess the overall direction of Australian foreign policy under his leadership. No doubt he would say, as with other areas of policy, that current Australian foreign policy is a case of ‘continuity with change’. But what precisely is the continuity? And how much change is occurring?

Understandably, given the events in Brussels earlier in the week, Turnbull focused on terrorism in the first part of his address. There was a gentle criticism of European governments that have presided over a “perfect storm of failed or neglected integration” in comparison with the “inclusion and mutual respect” underpinning Australia’s successful multicultural society. In relation to ISIL, Turnbull argued that both military force and a political settlement were needed. While Australia was contributing to the former (although it is difficult to evaluate progress), it was clearly only a minor player in relation to a political settlement, whether one focuses on Syria or Iraq.

The major part of the address had a strongly economic emphasis, focusing on Asia as the region where “opportunities are most abundant”. Turnbull’s hope is to preside over and encourage an “ideas boom” in Australia that will position the country to take advantage of these emerging opportunities. While China remains important in this respect, with the free trade agreement with China providing a facilitative framework, the Prime Minister paid particular attention to India and Indonesia as new lands of opportunity. The use of the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ highlighted the growing significance of India. Turnbull also views free trade agreements with Japan and South Korea favourably, as well as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

While the main emphasis in the address was on economic issues, Turnbull did not neglect the strategic dimension. Again the main emphasis was on Asia, with particular reference to the importance of the United States and its framework of alliances, including ANZUS. Linked to the changing economic situation, Turnbull referred to the changing balances in the region, in turn requiring a stronger effort by Australia – a theme in the recent Defence White Paper. Turnbull also takes a negative but diplomatic position in relation to China’s policy in the South China Sea. More broadly there was no reference to “soft balancing” against China but cooperation with the US, Japan, India and ASEAN being important.

Overall one can see a strong emphasis on the Asian region, with particular attention to the economic aspect. Global issues received less attention, the main exception being the threat of international terrorism. There was some attention to the strategic dimension of Australian involvement in the Asian region, focusing on the US role but in a broader multipolar context.

Interestingly, although perhaps unsurprisingly, climate change was only a minor point in the address, the emphasis being on technology and innovation as a means of adapting. The issue of asylum seekers and refugees was not mentioned.

Returning to the theme of “continuity with change” it is no doubt a truism to say that Australian governments have long focused on Asia as being central to Australian concerns. Since the 1960s this region has been of fundamental importance to Australian trade. Turnbull is the latest in a long line of Australian leaders highlighting this dimension while at the same time modifying Australian policy in the light of changes in the region and within Australia itself.

Turnbull is also not the first Australian leader to focus on the strategic dimension of Australia’s Asian engagement. His approach is nuanced, essentially amounting to “soft balancing” in relation to China without actually using the term.

In relation to Tony Abbott as Turnbull’s immediate precursor, it is clear that both prime ministers necessarily had a strong focus on the Asian region. However, relatively speaking, Turnbull has a stronger emphasis on the economic dimension. Abbott approached security issues in a more traditional way and was perhaps more attuned to traditional alliances. He was more focused on international terrorism as a threat, although the substance of policy as between the two prime ministers is essentially the same. Turnbull is more “modern” in the way he assesses many of the issues.

Identifying Australian foreign policy with particular prime ministers is far too simple. There are many factors, both domestic and international, that will influence the direction of Australian foreign policy. At the same time that policy is not predetermined and leadership can be important given the options that emerge within the broader context. However, that leadership extends beyond the prime minister to include other ministers and significant figures in government and civil society. We should not let the “presidentialisation” of Australian politics obscure that reality or restrict the opportunities for input from across the broader spectrum of politics and society.

Derek McDougall is a Professorial Fellow at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne. This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence. It may be republished with permission.