Trump's Ban-Aid Solution

The US administration’s suspension of travel and refugees from seven Middle Eastern countries on counter-terrorism grounds sits in judicial limbo. In the wake of the global outcry at its introduction, it is vital for policymakers, analysts and commentators to look beyond the drama and politics, and think through the real-world ramifications.

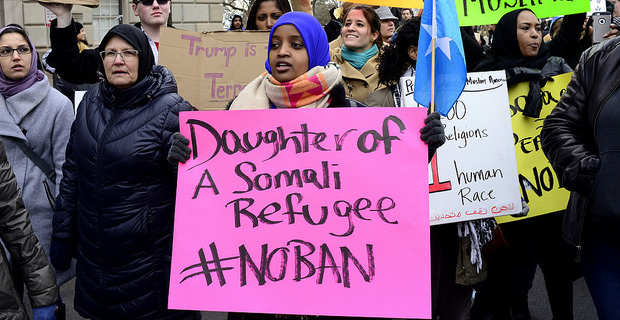

With all the emotion, protests and political condemnations around the world and the Twittersphere, it’s hard to glean what this does—or doesn’t—have to do with security and terrorism, let alone refugees who are at the heart of the issue. President Trump’s executive order states the purpose of the action is “protecting the nation from foreign terrorist entry into the United States”.

There are four key issues to note about this.

Domestic support

First, President Trump’s views on border security, terrorism and migration have been resoundingly clear throughout his presidential campaign; he has a mandate to take this action, and none of it is a surprise. And having acted upon this and other campaign promises, he has affirmed to his supporters that he will deliver.

Homegrown threat

Second is how this relates to the terrorist threat. A study by the University of Chicago’s Project on Security and Threats, published this week by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, gives us the most comprehensive analysis to date of the Islamic State (IS) threat to the US. One of the most striking findings is that terrorists are more likely to be homegrown than foreign. The study examined 112 cases of individuals charged with IS-related terrorism offences (and a small number who would have been but were killed or overseas) in the US between March 2014 and August 2016. It finds that 83 per cent of offenders are US citizens, including 65 per cent born in the US. A quarter of these US citizens were from migrant families; this means three quarters were not. Around half of those charged in relation to planned attacks were not only US citizens, but also converts to Islam. The group of 112 also included only three people who were refugees, with two arriving from Bosnia back in 1999 and the third, an Iraqi, arriving in 2012.

What to make of this? The study demonstrates that the profile of a terrorist in the US now is more complex than the popular picture and, at its simplest, the face of IS in America is actually more American than not. In relation to the executive order, it also tells us that suspending travel on its own cannot remove or substantially reduce the risk of attack.

But there is another side to the threat story.

We know IS is actively seeking to undertake attacks against US targets and will use whatever means available, both homegrown and foreigners travelling to the United States. Terrorist attacks in Europe undertaken by IS foreign fighters demonstrate this. We also know that countries around the world are managing the problematic issue of returning foreign fighters, who are leaving the Middle East as IS’s fortunes wane.

Managing borders

The third issue is border security, one of the fundamental responsibilities of nations. It is appropriate for the US to manage migration in a manner that reflects its national interests. The executive order only suspends travel for a period, it doesn’t ban travel or refugees. In coming months we can expect revised guidelines and criteria for travel to the US, as well as revisions to refugee intake. This is normal for governments to do; what is unusual about Trump’s executive order is the dramatic nature of the action and international response to it.

While some European and Middle Eastern countries also closed their borders to refugees and others over the past year—particularly those from Syria—these made less headlines than the actions of the Trump administration. Macedonia and Hungary closing their borders made the news in Western countries; Lebanon closing its borders to Syrians did not. British public opposition to unregulated migration was a major factor in the Brexit decision but this also appears to have been forgotten over recent months.

America first for refugees

Fourth is the complex and sometimes misunderstood matter of refugees. The US has for years led the world in the numbers of refugees resettled, along with Canada and Australia, and this is unlikely to change.

Refugee resettlement is different from temporary hosting of refugees, which typically occurs in countries adjacent to the affected area, as seen in Turkey. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees confirms that the preferred outcome for refugees is to return to their homes—and this is what occurs in most instances—but where this can’t be done and permanent resettlement elsewhere is the preferred outcome, refugee resettling countries are approached to work in concert with the UN. This is where countries like the US come in. So a suspension of refugee movement is a pause in the larger program, and in most instances is not affecting people fleeing to a first port of safety.

The Trump administration has stated it will be capping the refugee program for the year at 50,000. Based on figures for 2015 this would still make it the single largest resettlement country, more than double Canada at number two. With Europe still working through its refugee crisis, it’s unclear what this will mean for overall resettlement numbers, but recent events suggest there’s unlikely to be any appetite in Europe for a permanent resettlement program, as there is in the US and Australia.

While the Trump administration is already creating waves internationally, it is more important than ever for strategic policymakers, analysts and commentators to think clearly through and beyond the drama and politics. In a world of ‘fake news’, ‘alternative facts’ and policy in a 140-word tweet, this is more important than ever.

Jacinta Carroll has been the head of ASPI’s Counter Terrorism Policy Centre since August 2015. She joined ASPI after time with the Department of Defence and the Attorney-General’s Department.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.