Trumping Foreign Policy

While foreign publics don’t get to vote, their opinions matter to the United States. Even as the world’s sole superpower, the US requires the cooperation of other states to achieve many of its foreign policy objectives.

The United States suffers from an image problem. While the election of Donald Trump has ushered in a more polarised and uncertain period in American politics, it has also brought a sharp negative turn in perceptions of the US among publics abroad.

Such dynamics are, of course, not without precedent. During the so-called Global War on Terror initiated by former President George W. Bush, public opinion and international relations scholars noted the rise in anti-Americanism among publics abroad and sought to diagnose its causes.

What is more, these dynamics in global public opinion have real economic and political consequences. Heightened levels of anti-American sentiment, understood as negative affective feelings toward the US, are linked to decreased inbound tourism to the US, fewer international students electing to study in the US, reduced willingness to cooperate with the US in international fora, and reduced support for US-led conflicts.

In short, global public opinion matters to American interests. Public opinion also matters to bilateral relations between the US and its key allies, since their respective approaches to engagement with the US are shaped and constrained (in part) by domestic public opinion toward the US.

How do attitudes toward Trump among the publics of key US allies shape attitudes toward cooperation with the US in specific domains? Does invoking Trump produce a kind of reverse Midas touch among publics outside the US, in particular, the publics of its allies?

This article takes up these questions. It uses data from original survey-based experiments conducted in two middle-power states: Canada and Australia.

Public opinion among middle power publics

Canada and Australia are long-standing allies of the US with important economic and security ties. Admittedly, their respective bilateral trade relationships differ in importance. Still, there is no question that each bilateral relationship is important to each state; relations with the US is a politically salient issue in both countries, both at the level of policy and mass public opinion.

Further, each relationship has shown public signs of strain during the Trump presidency – whether the widely-publicised and abrupt telephone call hang-up (when the topic of refugee resettlement was raised between Trump and Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull), Trump’s attacks on the Canadian system of supply management in the agricultural sector, or the imposition of tariffs on steel and aluminium exports.

Aggregate public opinion in both countries would appear to bear the imprint of these recent events. For example, data from the Pew Global Attitudes Project show that 28 percent of the Canadian public in 2007 and 23 percent of the Australian public in 2008 expressed confidence in President George W. Bush to do the right thing in inter-national affairs. By contrast, in 2016 and late in the presidency of Barack Obama, 83 percent of Canadians and 84 percent of Australians expressed confidence. The following year in 2017, 22 percent of Canadians and 29 percent of Australians expressed confidence in Trump, returning to the low levels not seen since the G.W. Bush presidency.

Though these aggregate-level dynamics might plausibly be attributed to Trump, such causal attributions remain tenuous given existing survey-based evidence. How, then, does Trump’s persona shape the foreign policy attitudes of the Canadian and Australian publics?

To answer this question, I used surveys to clarify the effect of presenting a policy goal as endorsed (or not endorsed) by Trump on attitudes toward current policy issues in the Canada–US and Australia–US relationships.

Framing, public diplomacy and American foreign policy

Frames are a form of cue-taking. Elite cues transmit both information and the identity of the cue-giver. As such, messenger likeability and trustworthiness form part of the evaluation of elite cues.

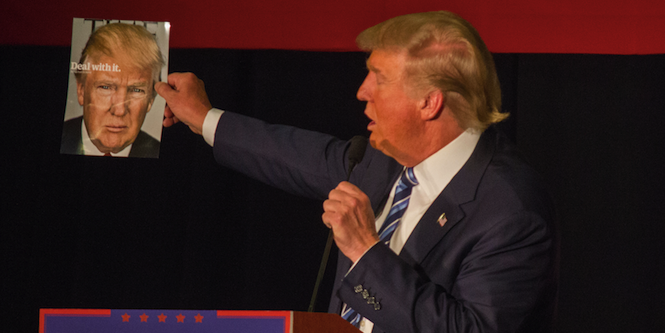

The images of US Presidents serve as an important element of a frame in American public diplomacy, with the President acting as ‘Diplomat in Chief’ in such efforts to persuade. The available evidence further indicates that efforts to persuade may succeed or backfire depending on the credibility and popularity of the President. Former President Barack Obama enjoyed high popular approval among publics abroad. Conversely, presidential framing involving an unpopular President may produce negative effects. In the second term of George W. Bush’s presidency, at the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, state visits by Bush decreased popular support for American policies.

In light of the available evidence, what about Trump? Trump is a historically unpopular President, with levels of confidence among the publics of advanced democracies comparable to George W. Bush in the latter part of his presidency, and well below the levels of confidence enjoyed by Barack Obama. The reasons for such lack of confidence are sufficiently clear: Trump’s public image is associated with national chauvinism, protectionism, and unilateralism, among other negative personal characteristics. It follows, then, that framing a particular goal of American foreign policy as endorsed by Trump (thereby making Trump a more salient consideration) ought to cause an erosion of support for that goal among publics abroad.

The results of the two studies presented here point to a negative ‘Trump effect’ in trade policy: among the Canadian and Australian publics, framing the renegotiation of NAFTA and the AUSFTA as endorsed by Trump serves to significantly decrease public support for revisiting both trade pacts. At the same time, Trump’s reverse Midas touch did not carry over to the other policy areas investigated (energy policy in Canada, and refugee policy in Australia). It may be the case that long-standing partisan debates on oil pipelines in Canada and refugees in Australia mean that both publics are thoroughly ‘pretreated,’ with attitudes already hardened, eliminating any potential for framing effects. Trump’s effect on US public diplomacy is therefore context specific: it ranges inconsequential at best to malign at worst, and is certainly never positive.

Previous research has demonstrated that Canadian and Australian foreign policy attitudes (particularly attitudes toward relations with the US) are shaped by political factors such as party identification and left–right ideology, with those on the political right tending to express more pro-American attitudes, and those on the political left expressing less positive attitudes. A Trump endorsement may thus exert different effects among different segments of Canadian and Australian voters.

Dr Timothy B. Gravelle is a Lecturer in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

This piece is an extract from Timothy’s article in Volume 72, Issue 5 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled ‘Trumping foreign policy: public diplomacy, framing, and public opinion among middle power publics‘. It is republished with permission.