Trampling the Grass: China-US Leadership Competition

As the APEC Summit showed, China-US competition will progressively revise the international system. Middle powers and smaller states alike will be continually called upon to make choices one way or the other.

For the Trump Administration, the zeitgeist is competition and the big competitor is China. The US National Security Strategy declares that the international system today is simply “an arena of continuous competition” where China is contesting the United States’ geopolitical advantages and trying to change the international order in its favor. The US National Defence Strategy notes the central challenge as “long-term, strategic competition” where China wants to gain “veto authority over other nations’ economic, diplomatic, and security decisions.”

C-words are now important. Competition is being adopted because the Trump Administration thinks the last two decades’ cooperation failed. Competition does not necessarily mean conflict. Cooperation is where two states work together for the common good; a win-win process. Conflict involves a serious disagreement between two states and implies a clash between opposing forces. Competition is different to both. Competition is not between two alone, but instead a contest between two states over a third party or object. A sporting analogy may help: athletes compete in an arena to win some prize. They don’t fight each other directly as during conflict, but instead seek to gain an external object while denying it to another.

The prize the United States seeks is clear: international leadership. The US frets about China because it is challenging contemporary American geopolitical advantages, because China wants to shift the international order away from a US-centered one to a Chinese-centred one and because if China gains a veto power over others the US will lose its veto power. It is arguably not wrong.

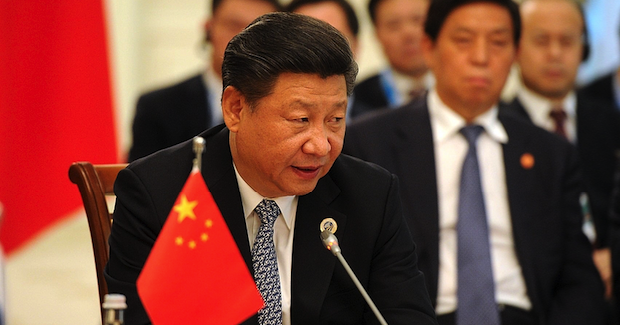

China wishes, at the least, to lead the East Asian region, to be respected – code for being obeyed – and to be able to decide other states’ policy choices. Offering advice on being obedient, Liu Qing of the China Institute of International Studies, a think tank under China’s foreign ministry, observes: “If Australia takes sides with the US, this would hurt the China-Australia relationship” including “trade investment, tourism and personnel exchanges.”

China’s strategy for leadership involves some positive aspects, including strategic partnerships, win-win economic proposals, important trading access and comprehensive engagement across political, economic, diplomatic, cultural and societal domains. There are also negative aspects, including helping authoritarian leaders like Syria’s Assad repress their citizens, large-scale infrastructure projects that create Chinese enclaves and loans that can potentially entrap and enfeeble poorer nations. While China may intend to do good in assisting lesser states, its methods can be criticised as predatory.

Similarly, the US strategy for leadership has pluses and minuses and, just like China’s, sometimes the rhetoric and the actions are at odds. The US has a durable alliance network that makes it a global power able to act globally. It has worked with others to create large multilateral institutions that give smaller states both a say at the table and a stake in an extensive rules-based international order. The US has generally also been able to harness soft power; its failures have generally been presented as failures of good intent rather than sinister machinations. The Trump Administration, though, seems dismissive of its alliance network, is actively dismantling global multilateral institutions, fights with democratic states while praising authoritarian leaders and unceasingly damages its soft power.

There are some implications.

First, Trump’s America is focusing on winning at geoeconomics, suggesting conflict, not competition. The Trump Administration sees the economic relationship in zero-sum terms: an American win means China loses and vice versa. China, however, will eventually end up the world’s largest economy. So the US is playing to China’s strengths. To succeed the US will need other’s help to tip the economic balance.

Second, the US is talking of decoupling from China. This process will cause considerable turbulence in the global economic and financial system. It will also combine with America’s efforts to dismantle the global trading system and abandon multilateralism for big power politics. All this won’t make people richer; instead we will all be poorer, including the US and China. The US apparently believes this price is worth paying; the rest of us haven’t been asked.

Lastly, China and the US paradoxically will need to cooperate to sustain their competition. They will need to maintain the international system in a form that their competition can be carried on within. China and the US both see international trade as central to their prosperity, albeit they want it on their own terms. In this, there is a danger of all states embracing autarkic policies as in the 1920-30s, sharply constraining international trade. More broadly, climate change is advancing; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sets out timelines when significant political impacts will start to be felt. China-US competition will be hard to sustain if or when mass movements of people from the warming tropics begin.

China-US competition will progressively revise the international system. Middle powers and smaller states alike will be objects of the two nation’s strategies, continually called upon to make choices one way or the other. Such choices are unlikely to be easy or beneficial. As the African proverb says: when elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.

Dr Peter Layton is a Visiting Fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, and author of Grand Strategy.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.