Tough Choices for Australia and Japan

No two countries have more at stake in the management of the US-China relationship than Australia and Japan. China is both Australia’s and Japan’s largest trading partner and both countries are crucial allies of the United States in managing Asia-Pacific security.

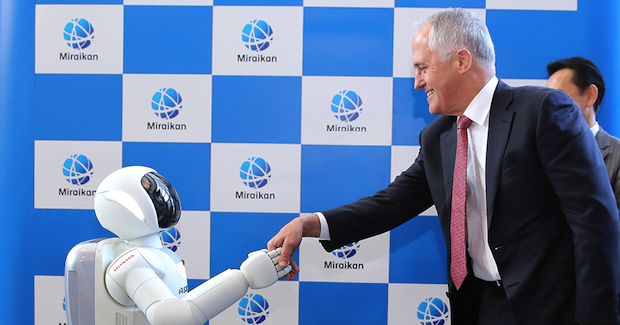

So the accelerated visit of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to Sydney today, and the rapport between the two, presents a more than welcome opportunity for Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to begin to work with his Japanese counterpart on shaping the strategies that will be needed to protect both countries’ interests in a dramatically changed international political and security environment.

The election of Donald Trump and the emerging character of his administration vastly complicates economic and security affairs for both countries. There are those in Tokyo and Canberra who pretend otherwise.

Wiser heads now have to face the realities.The old certainties that brought prosperity and a significant measure of stability to world affairs for over three-quarters of a century after World War II are under threat. The US anchor of the Western security system on which order in Asia and the Pacific has relied may be being weighed. Who knows where President-elect Donald Trump is heading?

Some may see US Secretary of State designate Rex Tillerson’s confirmation testimony before the US Senate yesterday as a clear signal of continuity and assertiveness of US predominance over the rising power of China in the South China Sea. On the contrary there has been no consideration by the new US administration of how the containment of China that Tillerson promised would affect the strategic position of the US or its allies in Asia or the vital economic relationship between the United States, Japan and Australia with China.

More disturbingly, the institutional edifice on which the economic certainty and political confidence in the US-led global order has been built—the postwar institutional framework that guaranteed economic openness and the prospect of economic and political security—is threatened with being dismantled. There are few in security circles around our region that appreciate what this will do to the global security outlook. There are also few who will readily cope with the Tillerson declaration. There is no preparation for it.

As Shiro Armstrong wrote yesterday “more than at any time in recent memory Australia and Japan need to be at the core of a coalition for openness in the global economy”.

The speed of developments is overtaking sound judgment and sound strategic positioning now is needed for half-good policy outcomes. If there is to be effective pushback against the threats to the order that has provided prosperity and stability in Asia and the Pacific, articulation of alternative strategy is urgent.

This is a time for assertive caution, not a time for meaningless assertion that nothing has changed in the world.

What leverage does Australia or Japan have in asserting alternative strategies that protect against the downsides of a Trump administration?

Both Japan and Australia are the location of strategic assets critical to the management of the United States’ global security system. As Turnbull and Abe properly assert Australia’s and Japan’s enduring interest in an open global economic system and the management of the relationship with China with nuance and certainty, they should remind our friends in Washington, privately but forcefully, of this critical US dependence on its allies, Japan and Australia, in projecting American power, not least through the ‘joint facilities’ in Australia so central to our partnership together.

Peter Drysdale AO FAIIA is emeritus professor, head of the East Asian Bureau of Economic Research and co-editor of the East Asia Forum in the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University.

This article was originally published on the East Asia Forum website on 14 January 2017. It is republished with permission.