Threat or Paranoia: Australia-Japan Relations in a Changing Asia

Deepening ties between Australia and Japan do not operate in a vacuum. They instead influence relationships in the region particularly with China.

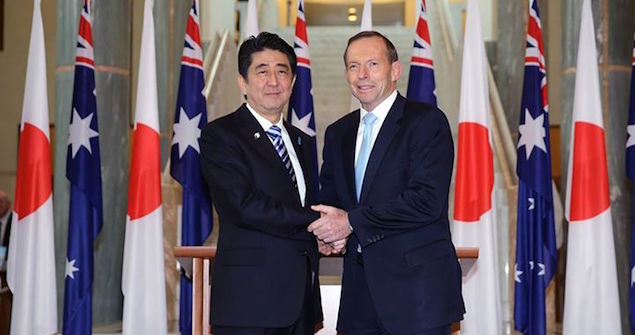

Australia-Japan relations are at a high. The personal engagement of Tony Abbott and Shinzo Abe is trickling down into increased defence and security co-operation between these two nations. Both countries viewed 2014 as a productive year and 2015 is set to continue in the same vein. Submarine deals, F-35 joint training, cyber-defence, anti-piracy and continuing close engagement on joint humanitarian relief exercises should all strengthen this relationship. Active dialogue on common interests and challenges will further improve relations.

In the past, commentators have questioned the wisdom and necessity of deepening ties between Japan and Australia. There is concern that such swift action could be perceived as a threat by China and as a step towards balancing or containment. Others contend that both countries are merely pursuing their own national interests and should not be concerned by Chinese paranoia. Each argument has its merits.

Bilateral defence co-operation does not happen in a vacuum. It operates in the context of an increasingly belligerent China that is pushing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour. It also functions alongside Australia and Japan’s bilateral ties with the US – a country concerned about its own future in the Asia-Pacific.

When we speak today of a rules-based order, we speak of the international regimes constructed by the West. China’s challenge to this rules-based order is not made in pursuit of anarchy, but is instead motivated by the desire to see a new order designed by China prevailing in the region.

Chinese aggression in the South China Sea therefore represents a testing of the waters. China is pushing the limits of the status quo, seeing how far it can extend its reach without ramifications. It has been said that Beijing is employing a form of guerilla tactics on an international scale; striking fast and then withdrawing, but extending a little further each time.

We must also remember that China’s interpretation of international law is different to that in the West. The Chinese approach appears to rely more on creative interpretation rather than attention to detail. This behaviour is certainly concerning, and it is therefore unsurprising that states like Japan and Australia should seek security in strong alliances.

China is unlikely to challenge the US outright in the Asia-Pacific in the near future. We cannot forget that the US retains significant military advantage; its defence spending is more than double that of China. The US has the support of Japan, South Korea and Australia in the region, among several others. Regardless of China’s posturing, the current alliance-building and balancing actions are unlikely to provoke a violent response for the time being.

That said, the day may come when China oversteps the mark, eliciting a forceful response. To avoid this situation, communication and openness are crucial.

Japan and Australia must engage with China as their relationship grows. They must clarify the benefits of their relationship to China, allaying Beijing’s concerns about the threats posed by strengthened Japan-Australia-US co-operation. Above all China must be involved in dialogue, not isolated from the international community. If the Chinese position is to be fully understood, its government must be invited into discussion and debate rather than discounted as a brazen rule-breaker. As the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) argues in its recent special report, China must be brought into the rules-based order in the Asia-Pacific. The success of such a pursuit is uncertain. Nevertheless, efforts toward this goal require active dialogue and collaboration, representing a far better path towards the maintenance of peace than isolation and second-guessing.

This is a situation in which Canberra should not step back and simply watch events unfold. Australia has a valuable role to play as a middle power; acting as a broker, a negotiator and an advocate for discussion between interested parties. By championing a rules-based order, Australia can strive to maintain peace in its region.

Sebastian McLellan studies a Master of International Relations at the University of Melbourne, and he is currently a research intern at the AIIA National Office. He can be reached at sebastian.mclellan62@gmail.com. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.