The US-Russian Space Station Mission is a Study in Cooperation

As space becomes increasingly militarised, it will become crucial for states to coordinate extra-terrestrial activities.

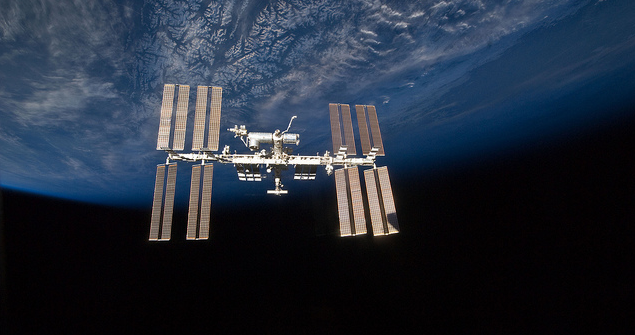

The unfortunate loss of the Russian Progress M-27M cargo vessel destined for the International Space Station (ISS) has highlighted the interdependence of the US and Russia in the project.

Despite such setbacks, this co-operation is to be welcomed by the international community. The ISS is probably the most complex and costly international infrastructure project ever undertaken. The 15 partners in the program have recently agreed to extend its operating life until 2024. It had earlier been slated for an end-of-life date of 2020.

Recent reports also suggest that the US and Russia are discussing the construction and operation of a new space station. This, presumably, would continue and extend the scientific and research activities of the current ISS.

The politics on Earth

These developments stand in marked contrast to the current state of relations between the two countries on more Earthly matters.

The events in Ukraine over the past 18 months have exacerbated an already tense co-existence between Moscow and Washington.

Russia wishes to (re)assert itself in a context of what it sees as a US-led NATO strategy to extend its activities and support, even to the borders of Russia itself.

For its part, the US views Russia as increasingly non-democratic and aggressive, yearning for its previous broad sphere of influence.

There is no doubt that the optimism of the early 1990s regarding the relationship between these Cold War protagonists has dissipated. What’s more, it is by no means clear as to how exactly this trend can be reversed or even halted.

Peace in space

This is where the impact of their outer space co-operation may help. The US and Russia (and previously the USSR) have always been the major space superpowers. Others (particularly China) are now joining their ranks.

The launch of Sputnik 1 by the USSR in October 1957, the first human-made object to orbit the Earth, heralded the dawn of the space age. It also led to the development of important principles for the legal regulation of the use and exploration of outer space.

International laws, developed largely through a United Nations-sponsored process, provided the framework by which the standard of living for all humanity has significantly improved. This is through services such as satellite telecommunications, global positioning systems, remote sensing technology for weather forecasting and disaster management and satellite television broadcast.

The prospects for future outer space activities offer tremendous opportunities for humankind, and a continued and enhanced co-operative ISS program will play an important role in this regard.

A crucial element underpinning the legal regulatory framework was the avoidance of armed conflict in outer space. The space race emerged at the height of the Cold War, when both the US and the USSR were flexing their respective technological muscles.

Military and strategic considerations were the driving force for the development of space-related technology. This was a period of considerable tension, with the possibility of large-scale and potentially highly destructive military conflict always lurking in the background.

Within this context, it was vital that international efforts were made to promote the peaceful uses of outer space.

A United Nations General Assembly Resolution, passed barely two months after the launch of Sputnik, emphasised:

[…] the common interest of mankind in outer space and recognizing that it is the common aim that outer space should be used for peaceful purposes only.

The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was established in 1958 and now describes itself as “one of the largest Committees in the United Nations”.

Space wars

Undoubtedly, space technology is being used for military purposes. The first Gulf War demonstrated the military value of space assets, such as satellites, and is often referred to as the first space war.

Space technology now forms part of the integrated battle platform for many countries. Space is often described as “congested, contested and competitive”, and military commanders consider that a hypothetical “day without space” – where a nation’s space assets would be disabled or jammed – would represent a national security catastrophe.

Nonetheless, the legal regime has thus far been remarkably successful in avoiding an actual war in space.

The UN Treaty rules confirm that outer space is not subject to ownership or territorial rights by prohibiting sovereign (or private) property claims.

This is a principle that not only reflects the practice of all countries from the beginning of the space age, but also represents an important proactive step designed to protect space from the possibility of conflict driven by territorial or colonising ambitions.

Undoubtedly, the ongoing development of technology and shifting nature of geo-political balances on Earth puts pressure on this extra-terrestrial status quo.

In January 2001, a commission headed by former US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, (in)famously warned of the possibility of a “Space Pearl Harbor” – a surprise attack on the space assets of the US during a crisis or conflict.

Such perceptions have driven a space arms race involving all of the major space powers. This is a worrying trend that must somehow be arrested.

Such issues fall outside of the self-imposed mandate of COPUOS, and have largely been left to the Conference of Disarmament. But this is an organisation that, in recent years, has had difficulty in even agreeing its agenda for discussion, let alone matters of substance.

Recognition of the fundamental sentiments of humanity that underpin international space law is therefore crucial in order to avoid the possibility of scenarios that do not bear contemplation.

Back to the ISS

The ISS project has brought together two of the world’s major powers in a co-operative venture that, despite some technical and financial problems, has provided a sense of hope about what the future holds for humankind.

The US and Russia are currently jointly engaged in the so-called “one-year mission”. An American astronaut and Russian cosmonaut will spend a period of one year aboard the ISS as part of a medical research project designed to provide further insights into the capacities of the human body to withstand the pressures of long-term space travel.

Despite the rhetoric and diplomatic manoeuvring on Earth, scientific co-operation between these two countries will, hopefully, continue in outer space. Of course, even these are, from time to time, affected by the machinations of terrestrial realpolitik.

But over the long term, both countries will hopefully come to the realisation that many of the very ambitious and potentially rewarding space activities that we currently can only dream of undertaking will require joint expertise, resources and co-operation.

And, along the way, one can only hope that maybe, just maybe, such extra-terrestrial co-operation can contribute to a greater sense of oneness on Earth.

Steven Freeland is a Professor of International Law at the University of Western Sydney. This article was originally published in The Conversation on 1 May 2015. It is republished with permission.