The UN Security Council as a Climate Governance Institution

On 17 May the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade concluded that climate change is exacerbating threats and risks to Australia’s national security. As Australia promotes its bid for a UN Security Council seat, what can the Security Council do to lessen climate insecurity?

Both Australia and the US are taking climate security seriously. The Australian Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee recently handed down its report on the implications of climate change for Australia’s national security and, despite the posturing of the Trump Administration, the US Department of Defense sees one of its most urgent issues as the implications for military installations and operations: Norfolk, Virginia, home to the North Atlantic fleet, is facing both rising sea levels and sinking ground. The 2016 Australian Defence White Paper recognised the implications of sea level rise for Australia’s Navy bases and that more extreme weather events would more frequently put military facilities at risk of damage.

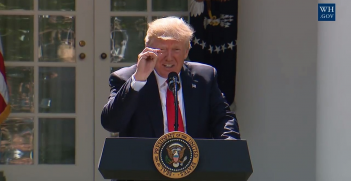

The evolution of global climate change governance has been a story of never-ending hope in the face of continuous disappointment. In such a context it might have seemed churlish to express disappointment at the provisions of the Paris Agreement. President Trump may be unimpressed by the Agreement, but the reaction to its creation was one of virtually unanimous relief if not approval. Only a few doubters pointed out that the combined promised mitigation reductions would not be of the order necessary to prevent the serious consequences of climate change and variability. The hope is that states will ratchet up their ambition over time. This may happen but, given increasing population size and the history of efforts to date, we must also consider the possibility that the nett impact of national efforts will still be inadequate and too late.

As the gap between the needed and realised mitigation widens and adaptation shortfalls manifest, so will the world experience increased climate insecurity. Climate insecurity may stem most immediately from an increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, bushfires and floods, or else it may be more indirect, deriving from economic shocks caused by an inability to insure homes, to rebuild communities fast enough after disasters or to grow food in newly desertified areas. In some situations a complex mixture of social, economic, environmental and political factors may well lead to human conflict and insecurity of a more traditional nature. Militaries are likely to have an expanded role in disaster relief missions.

The Security Council’s role

The UN Security Council is at the apex of the global security institutional architecture. And yet despite growing recognition of the security implications of climate change at a national level in a majority of countries and, indeed, by other international security institutions, the Council has to date played a notably minimalist role in the collective response to climate change.

The Council first debated climate security and energy in 2007 and in 2011 issued a presidential statement expressing concern at the possible adverse security effects of climate change. There has been a series of informal Arria-Formula meetings on issues related to climate change and the Council has responded to crises, including in Darfur and in relation to Ebola, that are widely understood to have been exacerbated by climate change. But momentum may be building: in 2017 the Council recognised in a substantive provision the adverse effects on regional security in the Lake Chad Basin of climate change and ecological changes.

The Council has thus so far taken incremental steps into this issue arena. Early champions of Council consideration of climate security included the UK and Germany, while the 2009 resolution of the Assembly resulted from an initiative of the Small Island Developing States. The contentious question as to whether the Council was inappropriately crossing into the purview of the General Assembly was in 2009 settled by the Assembly itself when it called on ‘the relevant organs of the United Nations… to intensify their efforts in considering and addressing climate change, including its possible security implications’.

It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that absent adequate mitigation and adaptation, the burden of proof will at some point shift from promoters justifying why climate change is an appropriate concern of the Council to opponents needing to justify just how the Council could legitimately avoid taking serious action to address climate insecurity. In 2011, the US Representative to the United Nations asserted that the Council would be derelict in its duties if it failed to respond. There may come a point at which compounding impacts of climate change together with other environmental shocks increases the appetite for bottom-up governance approaches to be supplemented by top-down approaches of which Council-led initiatives would be one of the more extreme forms.

Although the ‘elephant in the room’ in any consideration of Council action on climate change is the concern that climate change could in the extreme be used to justify intervention in the internal affairs of states, the Council has a whole range of policy tools at its disposal well short of intervention and its history is one of innovation in the development of policy tools. The Council could, for example, consider the use of ‘legislative resolutions’, incorporation of climate considerations into peace mission mandates, or the establishment of a climate change tribunal. It may also have an important role to play in responding to massive humanitarian disasters and economic, social or political disruption.

An important future debate will likely be analogous to that regarding the Responsibility to Protect; in the case of climate security, it may be a Responsibility to Prepare, as proposed by Caitlin Werrell of the Washington-based Center for Climate and Security, or a responsibility to respond in the event of large scale natural disasters.

For while at first glance involvement of the UN Security Council represents an extreme form of top-down governance, key to its playing any constructive role will be finding effective ways to work with multiple domestic and international agencies and multiple levels of governing authority. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is already working across the disaster relief spectrum to assist countries in need, but the operational capabilities of this agency may need to be complemented by strategic guidance, of which the Council is the ultimate source within the UN system.

Shirley Scott is a Professor of International Relations in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, UNSW Australia. Professor Scott’s research and teaching focuses on international law as a dimension of global governance, demonstrating the complex interplay between power politics and international law. She is Immediate Past Research Chair of the AIIA.

Charlotte Ku is Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Global Programs at the Texas A&M University School of Law. Previously, Professor Ku served as co-director at the Center on Law and Globalization and Acting Director of the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law at the University of Cambridge.

Their latest book, Climate Change and the UN Security Council, was published by Edward Elgar in March 2018.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.