The UK in the Indo-Pacific: Security Policy Lost in Translation?

Boris Johnson’s recent publication of Global Britain in a Competitive Age has resurrected questions about Britain’s position in the new geopolitical order. Britain’s tilt to the Indo-Pacific has prompted many to question the disconnect between reality and rhetoric in British policy.

For Australia’s policy wonks and strategists, understanding the meaning of Boris Johnson’s favourite term, “Global Britain,” can be an intellectual challenge. Thoughtfully, after several rewrites, the British prime minister has provided us with a new brochure, entitled Global Britain in a Competitive Age, reminiscent of Julia Gillard’s Australia in the Asian Century.

There are just over 100 pages, but no photographs, apart from that of a watery English sunset and a portrait of a prime minister in sore need of a haircut. These stand alongside a wordy foreword which reminds us that security threats and tests of national resilience can take many forms.

In 2021, BBC listeners and readers of publications such as the Daily Express could be excused for thinking the next war might be imminent and on familiar territory, the English Channel. This could be attributed to the frequency of insults being traded with the European Union over vaccine supplies and border delays caused by Brexit. The latter have led to a 40 percent fall in exports from Britain to the European Union since it left the bloc on January 1.

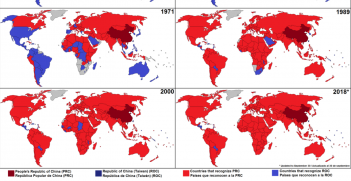

Despite this, the Integrated Review of Security Defence Development and Foreign Policy concluded that China poses the “biggest state-based threat” to economic security and presents a “systemic challenge” to national security, prosperity, and values. It concludes that Britain should “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific, a move enthusiastically endorsed by Johnson.

Johnson headlines his vision for the UK in 2030 with characteristic hubris: “We will be a beacon of democratic sovereignty and one of the most influential countries of the world… deeply committed to the Indo Pacific as the European partner… in support of mutually beneficial trade, shared security, and values.” Just how this greatness will be achieved by a country that has just chosen to leave the most successful trade bloc in the world is not explained, because it defies explanation. But as with Australia in the Asian Century, there is plenty of aspiration.

Controversially, Britain intends to enhance its status as a nuclear power, increasing its stockpile of Trident nuclear warheads by 80 to 260. This will reverse the decision of the Cameron government to reduce them. Then there is Johnson’s claim that Britain will have the “most effective border in the world” by 2025. Other innovations include a new counterterrorism operations centre, a national situation centre, and a national cyber force. Potentially the costliest proposal is Britain’s aspiration to be an international science and tech superpower by 2030.

Johnson is also hoping to splash the cash, with an extra A$10.8 billion for defence, on top of $21 billion for international climate change, and $540 billion already spent on domestic support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government document is not, of course, a capital raising prospectus. If it was, it would not pass muster. There are far too many unanswered questions, mostly about implementation.

The document sits well with many in the Tory shires who yearn for the days when Britain ruled the waves. They like the idea of a “Global Britain.” They are heartened to read in the chapter on the Indo-Pacific tilt that the region is “mission critical” for the UK. At least 1.7 million Brits live within the Indo-Pacific, a region projected to become the crucible for some of the most pressing global challenges in the next years. The meeting between Antony Blinken, United States Secretary of State, and his Chinese counterpart in Anchorage would indicate it is already a region of crucial importance.

The problem of the review comes from the proposed actions. They are often too vague, too general, or unrealistic. What, for instance, does the UK tilt to the Indo-Pacific mean? How would that help Britain deal with China’s aggression in the South China Sea, its failure to respect the “one country two systems” agreement on Hong Kong, or its well-reported violation of human rights?

Johnson has portrayed the Royal Navy’s plan to lead a task force through the Straits of Malacca and the main China Sea, led by its newest aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, as demonstrating “cutting edge military power.” This is a statement mocked by some defence commentators on the basis that Britain’s deployment of nuclear weapons against a state threatens a devastating cyber or biological attack on its population. After all, significant cyberattacks by Chinese and Russian state actors are now a weekly event.

Almost as perplexing to geopolitical analysts is that, despite its branding of China as an economic threat, the strategic review states the UK need to pursue a positive economic relationship with China, including “deeper trade links and more Chinese investment.” In fact, Johnson told Parliament that those calling for a new Cold War “to sequester our economy entirely from China” were mistaken. Jeremy Hunt, former foreign secretary, said he was worried that China is being designated simply as a systemic challenge “given the terrible events in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.” Sir Alex Younger, a former MI6 chief, told the BBC that China represented a “generational threat,” adding “[t]he idea that China would become more like us as it got richer and its economy matured is clearly for the birds.”

However, Australian politicians, facing an ongoing difficult relationship with Beijing, may well identify with Johnson’s strategy of confront where necessary and trade and cooperate where possible. One area where this is essential is climate change, an issue at the top of the agenda for Johnson’s hosting of the G7 summit in June, and the United Nations Climate Change summit in November. Interestingly, although the UK is no longer in the EU, Johnson has embraced the bloc’s long-standing view of China as simultaneously a partner, an economic competitor, and a “systemic rival.” Blinken is likely to accept this when he has his first meeting with EU leaders at the end of this week, reassuring them that despite his sparring with Yang Jiechi last weekend, the Biden administration will still seek agreements with Beijing.

The document was riddled with contradictions between words written and actions taken. One of the most significant discrepancies was Johnson’s boast that he has embarked on the biggest expansion in defence spending since the Cold War, “underpinned by a shift to a more robust position on security and deterrence.” Much of this was overdue, where Johnson replaced age-old tanks and aircraft with drones, robots, and other new technologies.

However, only this week a 10,000-person cut in Army numbers was announced. This has taken army numbers to the lowest level in 200 years. An enraged former defence chief told Times Radio this meant Britain could no longer engage in conflicts equivalent to either of the two recent Gulf wars, let alone recapture the Falklands or mount an operation in Rwanda.

The document talks of the United Kingdom as a union of countries with shared values, with the union being its “greatest source of strength” and national identity. However, right now, the union is at risk of being torn apart by government failures in the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement, which reintroduces a customs border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. More immediately, the Scottish general election in May will almost certainly lead to renewed demands for a second referendum on independence. Should that happen, the Polaris fleet may be forced out of Holy Loch and Australia may be asked to find some secure berths for part of the nuclear fleet. Thus, this may be a review of what a Global Britain might wish for, but it would not be wise to assume that this is what it will be.

Colin Chapman is a writer, broadcaster, and public speaker, who specialises in geopolitics, international economics, and global media issues. He is a former president of AIIA NSW and was appointed a fellow of the AIIA in 2017.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.