The TPP is an Inevitable Catch-22 for Australian Industry

The TPP and increasing global free trade are inevitable, however the effects are unknown, where one industry will flourish from the deal, another may wither away under the competition.

With the apparent imminent conclusion of the long negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership at hand, Australian business is clear eyed about the potential impacts – hugely positive for some and deeply concerning for others – of Australia’s growing freer trade agenda.

It is Australian industry which will implement the advantages of freer trade through the Agreement, how and when it is concluded. But Australian industry will also bear the brunt of rapid erosion of domestic markets. And it is industry which has the expertise to advise on the effect – both short and long term – of the proposed measures as they wash through our economy.

There is no doubt big parts of the Australian economy where we have or are seeking a competitive advantage in the production and delivery of key goods and services can benefit from a well negotiated, implemented and enforced freer trade agenda.

Think of the sectors where the government is rightly directing its focus to build innovation, collaboration and growth – advanced manufacturing, medical technology, oil and gas, resources and food and agribusiness. All these sectors, if the agreement is well crafted, can over time benefit from increased market access, especially in the high growth markets of the Asia-Pacific, as well as potentially greater access to investment and capital flows.

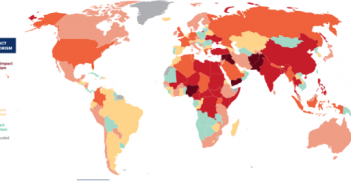

But at a time of significant economic restructuring and volatility, patchy consumer and business confidence, generally flat conditions, concern about global economic prospects, increasing fears about national and international security and wariness – as well as excitement – about the unknown consequences of technological and economic disrupters, the push to freer trade also causes unease for many in business. Questioners are not inevitable opponents. Even those who will be the most likely winners will be uncertain about the impact of the details until well after a TPP deal is signed.

It is, for many at the coal face of Australia’s relentless economic structural change, purely another risk factor. It will be added to conversations at board rooms around Australia on issues such as high costs, sluggish productivity growth, labour inflexibility, rising energy costs, tight energy markets and local procurement.

Ask some of our automotive manufacturers and suppliers, an industry already under significant cost and competitive pressures, who found the signing and implementation of trade agreements with Thailand, Korea and Japan to be the final blow to their domestic operations. Ask those operating in the rail and defence sectors under pressure regarding decisions on local procurement. Ask some who operate in the utilities space about their concerns for their sector about the impact of competition and investment from state owned enterprises. Ask those in the pharmaceuticals sector concerned about the potential impact on their intellectual property rights.

There is concern about the domestic impact across parts of all of the 12 economies at the TPP negotiating table. The list of areas of concern is a long one. The Japan-US imbroglio over agriculture and motor vehicles access into their respective markets, which has been at the heart of the last minute negotiations, is an example. Canada’s reluctance to open up its dairy sector is another. American sneaker manufacturers are concerned about a loss of jobs, production and research and development. Australian food and pharmaceutical manufacturers are concerned about a loss of intellectual property rights. There is concern across the board about the impact an agreement will have on the copyright and e-commerce laws of each signatory.

Australia already has free trade agreements with eight of the 11 other TPP participants – analysis shows the other three make up less than three per cent of our total exports. The first test of the agreement will be to assess if there has been harm done, compared with the existing agreements in terms of Australian market access or domestic competitiveness. The second test will be to assess what carve outs Australian negotiators have achieved. The third test will be to judge where the gains have been made. Then there will be the balancing of winners and losers.

Freer trade is happening. It is inevitable. After the TPP is concluded, Australian attention will turn to India and the Gulf States. The Australia-China FTA is set to be signed by the end of the month, with implementation from 1 January 2016 – another massive opportunity and challenge for Australian business. The Australian economy will adjust. Many tremendous opportunities will arise as Australian businesses hook into global supply chains. In many ways, we have no option but to be on the freer trade playing field.

But many local businesses, lacking investment, advanced product or access to our areas of natural competitive advantage, will struggle or fall by the wayside. For better or worse, the inevitable opening up of the global economy will lead to more dramatic shifts in our domestic business landscape. And there will be winners and losers.

Innes Willox is the CEO of Australian Industry Group (AiGroup). This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.