The Timor Sea Disputes: Resolved or Ongoing?

This week Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop and Timor-Leste’s Minister Agio Pereira signed a historic maritime treaty at the United Nations in New York. The agreement, which came out of UN Compulsory Conciliation (UNCC) proceedings initiated by Timor-Leste, has been construed by a number of media reports as resolving the dispute over the lucrative Greater Sunrise gas field. Unfortunately, the dispute over Greater Sunrise is far from being resolved.

Partly this reflects the misunderstood nature of the dispute around maritime boundaries and marine gas resources in the Timor Sea. As my 2017 article in the Australian Journal of International Affairs details, the Timor Sea dispute is actually a multifaceted set of interlocked contests. The different elements have been conflated in the public commentary.

There are three key sites of contestation: first, the creation of permanent maritime boundaries (and the attendant question of where these boundaries should be drawn); second, the appropriate split of upstream revenue from the contested Greater Sunrise field; and finally, the question of how the field should be developed. The latter issue has been the most intractable and was the crucial factor driving Timor-Leste’s abandonment of the previous Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) treaty.

Timor-Leste’s leaders—led by former guerrilla leader Xanana Gusmao—have argued that the gas should be piped to the south coast of Timor-Leste for processing. Successive Timorese governments have placed the Tasi Mane processing plant at the heart of economic development plans. However, the licensee consortium of gas companies led by Woodside has argued that this option is not viable. Alternatives including a LNG floating platform or backfilling the existing Darwin facilities have been proposed as preferred options.

This vital element of the dispute appears no closer to being resolved. If anything, it seems to be starting to escalate. Just before the signing in New York, Gusmao ratcheted up the rhetoric through a leaked letter to the UNCC panel, which blasted the independent experts who confirmed the unviability of Timor-Leste’s pipeline plan, as well as Australia for colluding with the gas companies.

Permanent maritime boundaries

The most important aspect of the treaty signed by Timor-Leste and Australian representatives this week is the delimitation of permanent maritime boundaries. This reflects an important step in the bilateral relationship between the neighbouring states. Since the signing of the CMATS in 2006, which placed a moratorium on boundary delimitation, Australia has been reluctant to engage with Timor-Leste on this issue. The demise of the CMATS treaty in 2017 reinvigorated Australia’s legal obligation to participate in boundary negotiations with Timor-Leste.

There is significant symbolic value in these new boundaries for Timor-Leste. Leaders and civil society organisations have long linked boundaries to the completion of full sovereignty, with Australia cast as an occupier of Timorese sea territory. Given Australia’s previous reluctance to engage, this can be interpreted as a moral victory for Timor-Leste.

Yet it also reflects clever statecraft from Australia. Giving Timor-Leste its sought-after boundaries allows Timor-Leste to claim its moral victory, while also allowing Australia to recast itself as a good international citizen, such as in a Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade fact sheet that argues that “Australia was committed to finding an outcome that would best support Timor-Leste’s future”. Furthermore, it allows Australia to head off claims of hypocrisy made when the foreign minister criticised China for undermining the rules-based order by ignoring the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling in its South China Sea dispute with the Philippines.

It is important to dig beneath the emotive discourses around sovereignty and Timor-Leste’s future. For one, if maritime boundaries are essential to completing Timor-Leste’s sovereignty then its sovereignty remains incomplete because it still needs to delimit maritime boundaries with Indonesia. Yet there is no groundswell of civil society activism in regards to this, which suggests that the issue all along has really been about oil and gas in the Timor Sea.

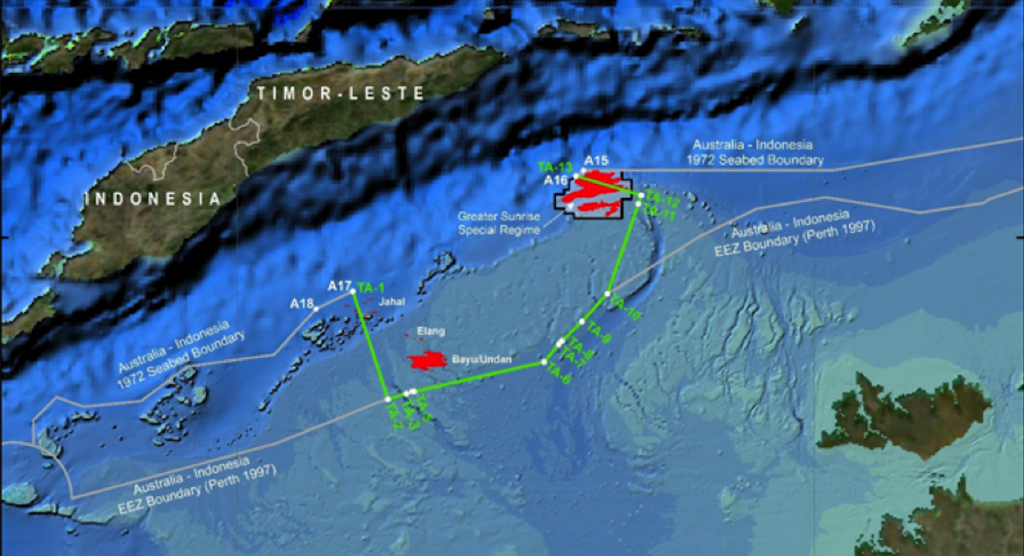

If this is the case, then permanent maritime boundaries have done little to bolster Timor-Leste’s access to oil and gas. As the map below demonstrates, the maritime boundaries have given Timor-Leste almost all the the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) encompassing the Bayu Undan field that has provided around 90 per cent of Timor-Leste’s national budget. But this is almost entirely depleted.

On the most important site, Greater Sunrise, the eastern lateral boundary that now runs through it suggests that Timor-Leste has been awarded 70 per cent, a significant improvement from the 2003 unitisation agreement that gave Australia 80 per cent and the CMATS which split the revenues 50:50.

But the boundary is deceiving when it comes to ownership because Greater Sunrise remains subject to joint development. Timor-Leste does not have full sovereignty of its share of Greater Sunrise because that field remains a shared sovereignty zone until the field is depleted.

The shared revenue concept and the pipeline

Materially, the boundaries are largely irrelevant because an agreement on developing Greater Sunrise is yet to be found. On the second aspect of the dispute, the treaty outlines a concept for the revenue split. Essentially, if Timor-Leste win the pipeline argument, it will get 70 per cent of the upstream revenues. If it does not get its pipeline, it will get an 80 per cent share.

The negotiators have only managed to get halfway on the problem of revenue share. Essentially, this clause is redundant unless Timor-Leste and the consortium agrees upon a development concept. The UNCC report is due mid-April, and it appears from the leaked Gusmao letter that the independent advice to the commission is that the pipeline is not viable. This is where the dispute seems likely to get ugly. By agreeing to maritime boundaries, Australia has deferred discussions about the pipeline to the consortium and Timor-Leste. Ultimately it has slipped out of taking responsibility for the most problematic aspect of the dispute.

Australia describes itself as neutral on the issue of the pipeline. Timor-Leste’s leaders have described the pipeline as non-negotiable. Yet independent oil industry experts have repeatedly described the pipeline as unviable, unprofitable and even dangerous.

Oil industry journalist Damon Evans wrote a piece excoriating the ‘arrogance’ of Xanana Gusmao and his ‘cronies’ in their refusal to back down from the pipeline. It is an honest and unflinching appraisal of the actions of some of Timor-Leste’s leaders, and well worth a read for those concerned with social justice for the Timorese. The reality is, if Greater Sunrise is not developed soon, the economic viability of the state will be undermined. This would have potentially wide-ranging and disastrous implications for the security and livelihoods of ordinary Timorese citizens as well as the hard-fought sovereignty and independence of the state.

Dr Rebecca Strating is a lecturer in Politics at La Trobe University. Her article “Timor-Leste’s foreign policy approach to the Timor Sea disputes: pipeline or pipe dream?” was recently announced as the winner of the Boyer Prize for best article published in the Australian Journal of International Affairs in 2017.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.