The International Criminal Court: New Legal Precedents

As we celebrate International Museum Day on 18 May, it is timely to consider the destructive impact of war on important cultural sites. Can the new legal precedents of the International Criminal Court prevent such atrocities?

Recent trials at the International Criminal Court (ICC) have led to the conviction and indictment of significant political figures for breaches of international humanitarian law (IHL). The world’s understanding of such law has since evolved to view rape as a weapon of war as a crime, along with the destruction of cultural monuments. These developments are significant, demonstrating the ICC’s pivotal role in pushing the frontier of international humanitarian law.

Rape as a tool of war

Between 2002 and 2003, former Vice President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Pierre Bemba was charged with two counts of crimes against humanity (murder and rape) and three counts of war crimes (murder, rape and pillaging). These all related to attacks carried out by the Congolese Liberation Movement (MLC) in the Central African Republic between 2002 and 2003. In March this year, Bemba was found guilty on all charges in a unanimous decision. Bemba’s case is significant because it represented the first conviction for the crime of rape at the ICC.

While the 1949 Geneva Conventions explicitly prohibits wartime rape, its use as a weapon of war has remained widespread. Furthermore, the failure to prosecute offenders tacitly legitimated its practice as an inevitability of war. This establishes an important legal precedent: rape as a tool of war can no longer be committed with impunity. It is also important to consider that this was the first time that the ICC has convicted with respect to command responsibility for the actions of their troops. For Amnesty International, the conviction makes it “clear that military commanders and political superiors must take all necessary steps to prevent their subordinates from committing such heinous acts and will be held accountable if they fail to do so”. Again, this ruling sets an important precedent for what is not acceptable during combat.

Destruction of cultural monuments

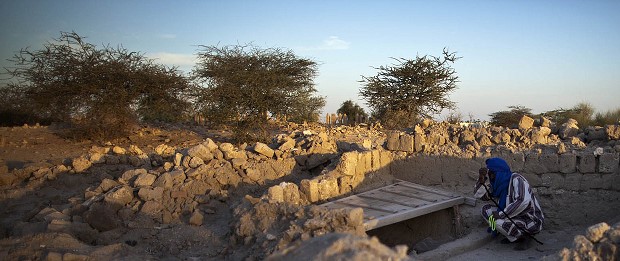

Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi faced the ICC for his role in directing attacks against and demolishing ancient mausoleums in Timbuktu, Mali. As with the number of the significant “firsts” identified above, this is the Court’s first war crimes trial for destruction of cultural monuments. The significance of this trial lies not only in the precedence that it establishes, but also the controversial decision by the Chief Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, to pursue these particular charges.

When announcing in 2013 that the ICC was opening an investigation into crimes allegedly committed in Mali, Bensouda determined that there was a “reasonable basis to believe that the following crimes were committed: (i) murder; (ii) mutilation, cruel treatment and torture; (iii) intentionally directing attacks against protected objects; (iv) the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgement pronounced by a regularly constituted court; (v) pillaging, and (vi) rape”. The fact that there is video evidence of Faqi’s crimes is obviously important; it strengthens the prosecution’s case at a time when, in light of the failed Kenyatta and Ruto prosecutions, the ICC needs a win. However, as with the Bemba case, the real significance lies in the extension, through judicial interpretation, of what is not acceptable during combat.

Of course, this is not the first time culturally significant buildings and artefacts have been targeted and destroyed during war. Nor is it the first time individuals have been held responsible for such destruction. But while the ICTY found individuals responsible for the attacks on Dubrovnik and the destruction of the Mostar Bridge, more recently those responsible for the destruction of Afghanistan’s sixth-century Bamiyan Buddhas, the looting of Cambodia’s Hindu temples and the destruction of Assyrian statues from Nineveh have gone unpunished. In pursuing Faqi for the alleged destruction of 10 protected and culturally significant buildings in Timbuktu, the Court is demonstrating not that more high profile atrocities are of lesser importance, but rather that deliberate attacks on a people’s culture and their beliefs should no longer go unpunished.

A ridiculous role?

It cannot be argued that the Court represents a panacea for determining what is not acceptable during conflict. There is still a number of notable shortcomings. For a variety of reasons, the Court is unable to investigate the numerous crimes and atrocities committed during the conflict in Syria. Nor is it able to open an investigation into suspected war crimes that characterised the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka. Thus, the claim made in the Statute’s preamble “affirming that the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole must not go unpunished” can at times seem merely aspirational.

Likewise, the ICC is often the subject of ridicule. In a number of African states, most notably Kenya, it is viewed as a Western tool of imperialism, a mechanism for “hunting Africans”. In other quarters, so long as three of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (the United States, China and Russia) remain non-signatories to the Rome Statute, the Court is nothing but an expensive white elephant. Finally, as part of a broader rejection of the legitimacy of international law, opponents of the Court argue that its reliance on the cooperation of often uncooperative states to ensure the arrest and extradition of indictees (best reflected through the continuing non-arrest of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir) means that the justice that it might be able to administer is at best selective and at worst arbitrary.

The ICC is the most recent development in the long evolved attempt to articulate the need for limits during conflict. The Court provides a hitherto non-existent means of prosecuting the worst violations of international humanitarian law, simultaneously expanding understandings and expectations of what is not permissible during war. Furthermore, it provides a counter to legitimating the use of force through appeals to raison d’état by extending legal and moral constraints to the realm of international affairs.

Dr Matt Killingsworth is the head of the Politics and International Relations of the School of Social Sciences at the University of Tasmania. He is the author of Civil Society in Communist Eastern Europe and co-editor of Violence and the State. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.