The Future of Turkish Politics After the Elections

Late last month, Turkey went to the ballot box for elections that ended Erdoğan’s need for state of emergency rule and formally legitimising his extended executive powers. What does this mean for the future of Turkish politics?

On 24 June, Turkey went to both parliamentary and presidential elections. Since March 2014, Turkish voters have gone to the ballot box five times: two parliamentary elections, one local, one presidential election and one constitutional referendum. If we count the failed coup attempt on 15 July 2016, there is no doubt Turkish people have been experiencing exceptionally turbulent politics in the last five years.

What was at stake in the elections?

The main reason for turbulence was President Erdoğan’s push for more power, and the consequential elimination of most checks and balances in the Turkish political system. The coup attempt allowed Erdoğan to have de facto executive presidential rule, due to the declaration of a state of emergency on 20 July 2016 just four days after the attempt. Since then, the state of emergency has been extended seven times and Erdoğan issued 31 decrees, all sweeping, to even include non-systemic arrangements such as those related to the use of snow tyres or the status of subcontractor workers.

In April 2017, while under the emergency rule, voters approved amendments to the Turkish Constitution. This was done by a national referendum that passed by a slim 51 to 49 per cent margin. It transformed Turkey’s parliamentary system into a presidential one with executive powers in the hands of the president. The referendum ushered in a transition period. The full executive powers would be effective after the first parliamentary and presidential elections.

Finally, the elections of last week signalled the end of transition to the powerful executive rule. Despite Erdoğan using the state of emergency to rule the country since the coup attempt, his excessive power only became institutionally settled and constitutionally legitimate with the results of the elections.

The election results

In the presidential elections incumbent president Erdoğan obtained 52.5% of the vote against candidate of main opposition centre-left Kemalist İnce’s 30.5%, pro-Kurdish Demirtaş’ 8.5% and nationalist Akşener’s 7%.

In the parliamentary elections, of the People’s Alliance parties, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) received 42.5% of the vote and the Turkish nationalist far-right party MHP received 11%. On the other hand, out of the rival Nation’s Alliance parties, the secular centre-left party CHP secured 22.5%, Akşener’s nationalist İyi Party 10% and Saadet, a minor conservative party received 1.3% of the vote. Lastly, pro-Kurdish HDP scored 11.7%, which acquired 67 seats for the party.

In parliament, AKP now has 295 seats out of 600. With the support of the far-right party MHP, Erdoğan will be able to dominate the Parliament too.

Political blocs and voting behaviour of the Turkish electorate

The results in both elections were a repetition of the previous ones with regard to voting patterns, and the winning and losing blocs. Furthermore, the results once more confirmed the dominance of nationalist-conservative base among the Turkish electorate; a large base which continued to be consolidated by Erdoğan. However, there seems to be a shift towards Turkish nationalism inside the dominant bloc. While İyi Party, a splinter group from MHP, could obtain nearly the same share of MHP’s vote in the November 2015 elections, MHP was able to compensate the loss from within its alliance. Erdoğan’s AKP lost votes in 71 of 81 provinces mostly to their alliance partner MHP.

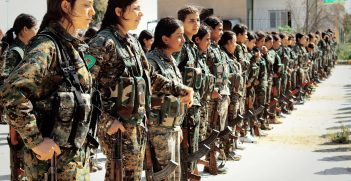

The performance of HDP, the party of the Kurdish movement in Turkey, was striking as it lost votes in their stronghold Kurdish majority provinces of the southeast, together with an increasing share in western metropolitan areas of Turkey. It is difficult to deduct how much of the loss in southeast Turkey was a result of ever-increasing presence of mostly pro-MHP and pro-AKP security personnel. It is significant that one third of HDP vote came from three metropolitan cities of Turkey: Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. Noting that most HDP candidates in western Turkish metropoles were of a socialist background, the party may incorporate in the future a broader agenda through an alliance of different Turkish socialist groups with the Kurdish movement.

Erdoğan’s election winning strategy in the last 15 years has been to consolidate the large right-wing vote, which has a wide range from conservative voters and far-right nationalists to right-wing liberal groups. Identity politics has dominated the political field over policy issues, rule of law, democracy and the economy. The tactic of fusing polarised groups rendered voter shifts among different alliances negligible. Even the 20% depreciation of the Turkish lira and a hike of the rates as high as 17.5% in the five months preceding the elections did not change many voter decisions.

Changes to the political system

Turkey has constitutionally become a one-man state after the June 24 elections. The President will have the constitutional right to issue presidential decrees in any policy matter. The elections are the end of transition period from de facto sultanism to de jure sultanism. Now Erdoğan has the jurisdiction to rule with firmans, or presidential edicts, just as the Ottoman sultans did.

The cabinet structure of the parliamentary system will be removed and the office of the prime minister and the old ministries responsible to the parliament will be abolished. On 4 July this week, President Erdoğan issued the first decree to introduce a new ministerial system. He will be able to appoint anybody as minister and the appointee will be responsible only to the President.

In the new system, 12 judges out of 15 in the Constitutional Court are appointed directly by the President, and the remaining three by the Parliament. What is even more detrimental to judicial independence, is that out of 13 members in the Board of Justices and Prosecutors, four are appointed by President and seven by the Parliament.

All crucial institutions such as the National Intelligence Organisation, Chief of the Army, National Security Council, and Department of Defence Industry are now under the umbrella of the Presidential office.

Not only the rule of law but observance of law has been declining for some time in Turkey. With the extreme concentration of power in the President’s office, there is an increased risk of arbitrary rule.

Impact on Turkish foreign policy

Turkey has many security threats in her region. However, the existing discourse about Turkey’s foreign policy will continue to be dominated by a blend of populism, Islamism and Turkish nationalism. As a fishing tactic for the conservative and nationalist voters, this discourse makes large use of anti-Western themes in discussion of Europe as well as anti-Kurdish rhetoric in relation to Syria.

Both the direction of foreign policy discourse and foreign policy decisions are controlled by the one man. Erdoğan’s preoccupation with domestic issues may drive loner behaviour in Turkey’s foreign policy. However, in relation to Syria and Turkey’s partners the US and the EU, Erdoğan will need to satisfy his Turkish nationalist allies, which are even more powerful now. On the other hand, harsher economic conditions in Turkey will force Erdoğan towards a reconciliatory policy for the EU, Turkey’s largest trade partner and the US, its most important military partner.

Looking towards the local elections in March next year, Erdoğan will find it harder to reconcile policy measures to cope with worsening economic prospects and the need to cater to populism.

Dr M. Murat Yurtbilir is an Associate Lecturer for the Centre for Arab & Islamic Studies at the Australian National University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.