The Future of the Republican Party: Can Trump’s Grip Continue?

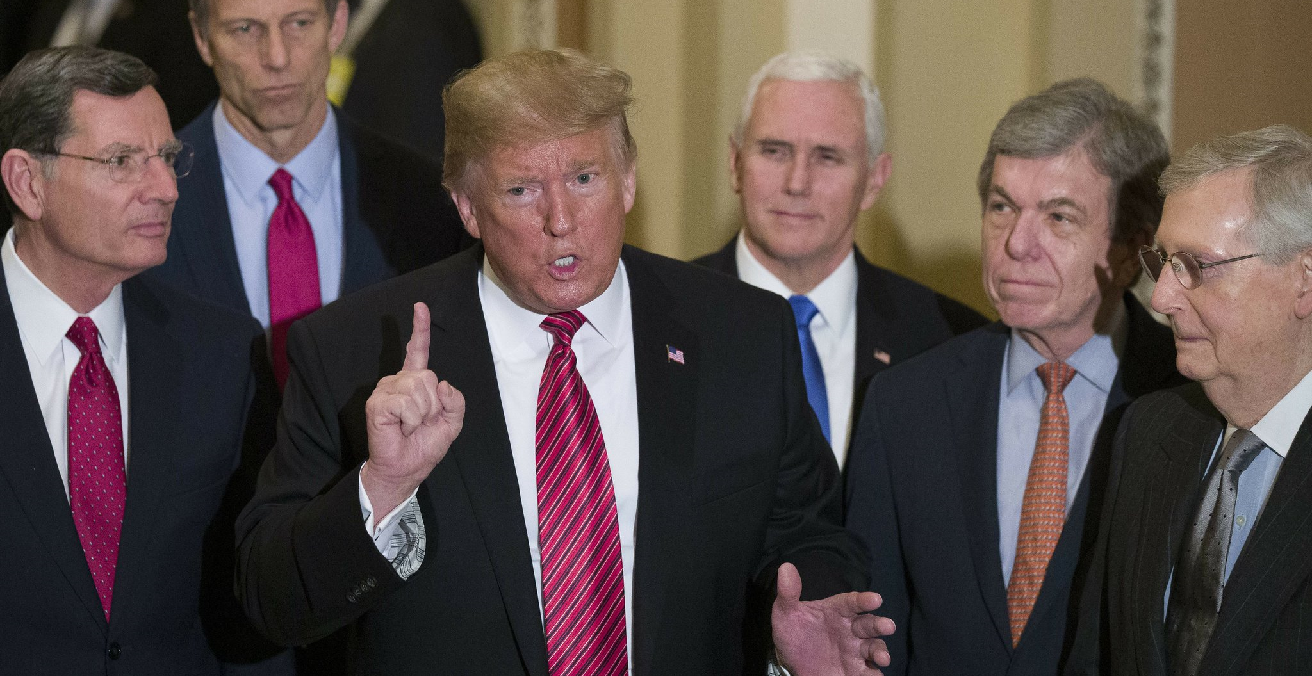

The vote for Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial and subsequent acquittal in the Senate fell largely along partisan lines. It was yet more incontrovertible proof of a five-year long process of “hostile takeover” of the Republican Party.

Despite the seven Republican senators that voted to convict him, the Grand Old Party (GOP) has become Trump’s party, and party dissenters assume this role at their own peril, mainly by diminishing their prospects at the ballot box. Yet, there is a broader dynamic at play here concerning party politics in the United States, which in turn paints a slightly more complicated picture. Primarily, the 2020 elections have confirmed the tripartite nature of American political parties. The first part is the so-called party-in-government, which is made up of officeholders. The second is the party machine, which supports the candidates at all levels of government in all phases of the electoral cycle. The final part relates to the party in the electorate, which reflects the preferences of registered members and supporters.

Seen through this lens, it would be most accurate to describe the GOP electorate as the most Trump-friendly part of the party. The party machine and leadership tend to be more divided regarding the extent to which they are willing to allow the former president to influence the party’s fortunes, which clearly puts them at odds with Trump’s base. We have seen this in a number of examples – from the Georgia GOP leadership not willing to kowtow to then-President Trump’s insistence to compromise the integrity of vote count, to the now Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s condemnation of President Trump’s role in the January 6 insurrection.

Granted, there have also been state officials who have censured their representatives for voting to impeach the former president. Equally, McConnell ultimately voted to acquit him. However, these decisions, much like the deference to Trump’s agenda during his time in the White House, were mostly a product of calculated politicking. This is certainly not something that makes these moves any more excusable. If anything, it shows that political survival trumps principles even when it has proven to be deeply corrosive to American democracy. It it is also a testament of hyper-partisanship and polarisation under which even those who are perceived as Trump’s most vocal Republican critics ended up voting with him. Furthermore, it has also revealed the GOP’s recognition that structural factors tend to favour the Democratic Party’s hold on power, which made conservatives undermine democratic institutions and break long-held norms.

Trump-era scholarship is replete with high quality analyses of how the 45th president represents a long-established ethnonationalist and populist strain within the Republican Party, as well as in American politics more broadly. In that sense, we can talk about Trumpism as a feature of GOP politics before Trump put his signature trademark on it. Rush Limbaugh’s recent passing was a good reminder of how conspiratorial, nativist, racist, and misogynist views became a mighty force in Republican politics at the end of last century.

Its latest incarnation became appealing in 2016 due to a combination of cultural and material factors. Namely, as a candidate, Trump galvanised voters around the oft-repeated American conservatives’ grievances that religious white communities have been under threat from progressive immigration and social policies that were enacted during the Obama era. He combined these messages with a potent evocation of deindustrialisation and offshoring of jobs, primarily in the Midwest, which he pinned on the Democratic Party, the era of hyperglobalisation, and free trade agreements. In that sense, Trump’s legacy is one of turning the party firmly towards the white working class.

While all of us America-watchers are still recovering from the 2020 election campaign, we are just twenty months away from the 2022 midterm elections, which will tell us more about the strength of Trump’s grip on GOP. One of the most helpful insights, as well as one of the underreported stories of the past election cycle, is the fact that Republicans managed to defend and solidify their control of state legislatures, which is going to be extremely important for redistricting this year, given that 2020 was the Census year. Given that Joe Biden’s election failed to help Democrats in the House of Representatives, where their majority lead narrowed following last November’s election, Republicans might be able to pick up extra seats in 2022 aided by the opportunity to gerrymander congressional districts.

With that in mind, there are two scenarios one can envisage. One is informed by the Tea Party “revolution” of 2010, which was, on the surface, seen as an outburst of populist rage, even when it was generously bankrolled by GOP megadonors. Such a scenario would see the election of more Trump-like candidates, who will probably be campaigning on a tested and contradictory mix of grievance-based messages on the one hand, and appealing to the working class minority voters on the other.

A different scenario, which would be an early sign of Trump’s repudiation, would entail selecting candidates who could court moderate Republicans in the suburbs. Their decision to swing support behind more centrist Democratic candidates in 2018 midterms was the key factor that resulted in a divided Congress between 2019 and 2021. The ability to attract these voters will in no small part depend on the success of Biden’s relief efforts and legislative track record. Republicans in the Congress are already poising themselves for obstruction. Failing that, they will aim to portray the incumbent as too extreme and subservient to the left wing of the Democratic Party.

Until then, the months ahead will deliver plenty of imagery that will aim to make the former president appear important, as he is featured in conservative media and at prominent Republican Party events. His appearances will be pored over and analysed to determine his ability to set agenda on legislative matters and consequently have a tangible impact. At the same time, we can expect a slew of legal battles to accelerate now that he is no longer shielded by presidential immunity. Despite his unique ability to evade the consequences of the rule of law, these court proceedings will undoubtedly make him a more diminished figure in national politics.

Dr Gorana Grgic is a jointly appointed lecturer at the United States Studies Centre and the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.