The Diplomacy of the Kitchen Table

Over the past 15 years, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has grown from a grassroots movement to a major international coalition. The success of ICAN in turning the Nuclear Ban Treaty into a reality shows the power of non-state diplomacy.

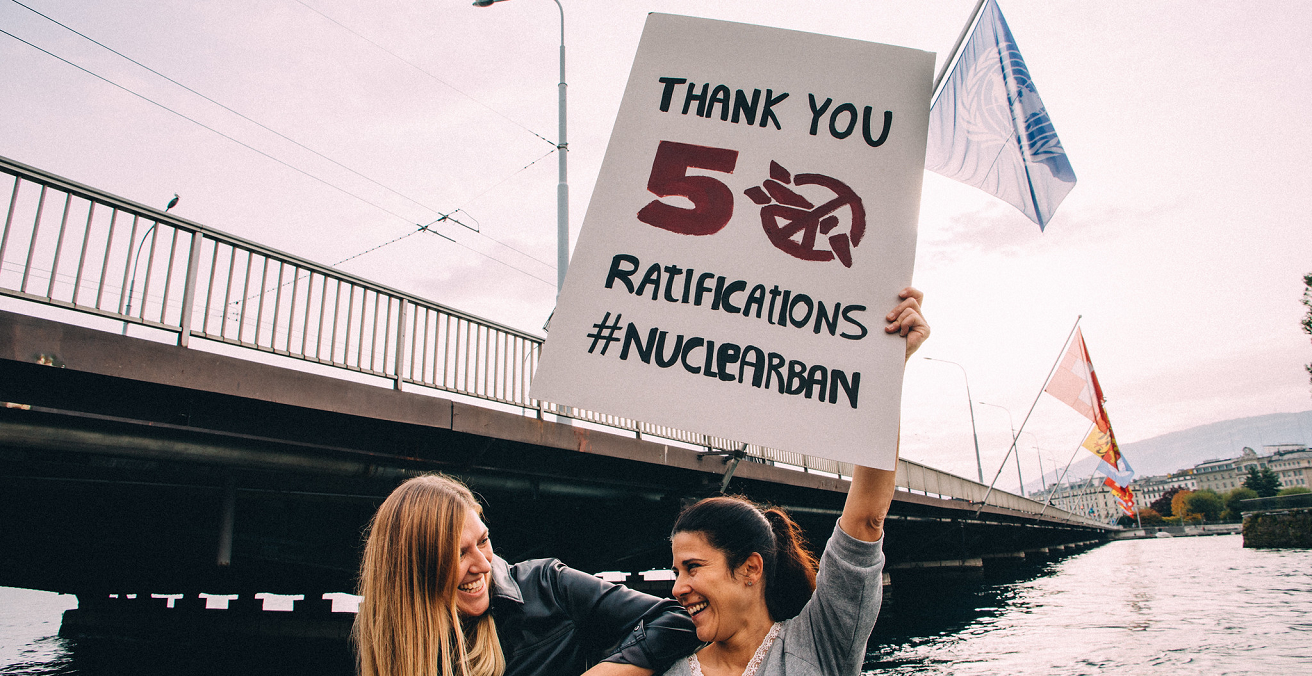

On 22 January, the Nuclear Ban Treaty entered into force. For its ground-breaking work promoting the treaty, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) received the Nobel Peace Prize. Looking at ICAN’s growth from a small group in Melbourne to an influential voice in global nuclear debate demonstrates the potential power of non-state actors in international diplomacy.

The makings of an international diplomatic campaign

ICAN was formed by a small group of long-term nuclear disarmament campaigners beginning in 2005, with a formal launch in 2007. Drawing on their decades of experience in non-proliferation, one of ICAN’s first initiatives was to try to build a campaign emulating the earlier International Campaign to Ban Landmines that led to the Mine Ban Treaty.

ICAN’s simple strategy was to call on all the countries in the UN to pass a law that would outlaw nuclear weapons. It rapidly spread globally and became a worldwide network of non-government organisations, all united in the belief that disarmament is the only way to eliminate the threat of nuclear weapons, including errors and accidental use.

Some of the founders have shared insights in public forums about ICAN’s strategies, including how they secured philanthropic support for the initial campaign and how they attracted volunteers. ICAN has always been explicitly intergenerational, drawing on experienced activists while ensuring prominent involvement by young people.

A vital element was getting buy-in from existing anti-nuclear organisations, such as the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW) and the Medical Association for Prevention of War (MAPW). ICAN’s early founders used their existing networks, such as through the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, to ensure that the campaign was both global in scope and collaborative in approach.

One of ICAN’s founding principles was building a broad and inclusive coalition that showed respect for and added value to “the many organisations who have campaigned long and hard for nuclear disarmament.” This positioned it as a force multiplier rather than as a competitor, and enabled it to draw on previous work, such as by the International Committee of the Red Cross.

ICAN consciously employs psychological insights in its strategies to engage and motivate, including through sharing the testimony of nuclear weapons survivors. One of its principles is to “utilise and balance horror, humour and hope” to help overcome the “denial and psychic numbing associated with the enormity of the nuclear threat” and to motivate action. ICAN is now a coalition consisting of several hundred NGOs, from local peace groups to global federations representing millions of people.

New diplomatic actors

According to one of its founders, Dimity Hawkins, ICAN always aimed to mobilise grassroots support: “We wanted to take these conversations out of the hallways of the UN and to bring them back to the kitchen tables, to the classrooms, to the streets and to the lecture theatres.” This suggests an awareness of the gap between citizens’ perception of the serious threat of nuclear weapons compared to their governments.

ICAN is a good illustration of the power of non-state actors and the way that diplomacy now includes much more than just official diplomats. In recent years I’ve been researching the role of new diplomatic actors including sister cities, think tanks, sports diplomacy, international education, student mobility, and corporate diplomacy. What’s clear is that, as Parag Khanna memorably described it, diplomacy is no longer the “stiff waltz” of states but a “jazzy dance” of the masses. He uses the term mega-diplomacy to describe the coalitions of “ministries, companies, churches, foundations, universities, activists, and other willful, enterprising individuals who cooperate to achieve specific goals.”

Judging ICAN’s success

ICAN was awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize “for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons.” While this was a thrilling moment, I suspect that its founders will be more excited by seeing the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) become a reality. In July 2017, 122 nations voted to adopt the treaty at the United Nations in New York. With the 50th ratification, it will now enter into force.

With none of the nuclear powers signing on, the TPNW is basically declaratory. It doesn’t cover issues like verification that would be needed in a genuine nuclear disarmament treaty. What it aims to do is to stigmatise nuclear weapons, conveying the normative view of the international community that these are immoral weapons that should be banned. This has already had some impact, for example on investments by sovereign wealth funds and financial institutions. The longer-term hope is that it puts pressure on nuclear weapons states to re-engage with disarmament and on allies and partners that depend on these nuclear weapons.

The Australian government doesn’t support the TPNW as it perceives it to be inconsistent with the US nuclear umbrella. Then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull did not offer any congratulations to the first Australian organisation to win the Nobel Peace Prize, in a move that co-founder Tilman Ruff has described as “small-minded and mean-spirited.” ICAN continues to lobby the Australian government to adopt the treaty.

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons is a case study that shows how much can be achieved by non-state actors. On other issues – from climate change to antimicrobial resistance to lethal autonomous weapons – citizens don’t have to wait for government to engage internationally. As former director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute Geir Lundestad reminds us, Nobel Prize winners are “often just more or less ordinary people who have tried to do something useful for peace.”

Melissa Conley Tyler is Research Fellow in the Asia Institute of The University of Melbourne after transferring from her role as Director of Diplomacy at Asialink. She served as National Executive Director of the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) for 13 years and was honoured as a Fellow of the AIIA in 2019.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.