The Chutzpah of the Iraq War Neocons and Fellow Travellers

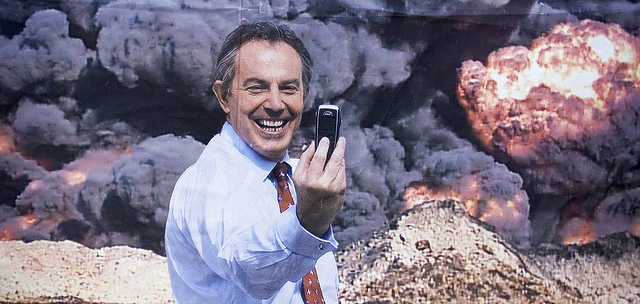

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair has recently denied that the lightning advance of ISIS could be blamed on the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but was instead attributable to the failure to intervene in Syria last year. Are we to admire Blair for his chutzpah or condemn him for his shamelessness?

Two years ago, Nobel Peace Laureate Desmond Tutu condemned the ‘immorality’ of the Iraq invasion: ‘in a consistent world, those responsible for this suffering and loss of life should be treading the same path as some of their African peers who have been made to answer for their actions in the Hague’. Like the indestructible Terminator, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair popped up recently to deny that the lightning advance of the bloodthirsty and ruthlessly efficient ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, covering the Levant across Iraq and Syria) could be blamed on the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Rather, in his parallel universe, the fault lies in not intervening in Syria last year to topple President Bashar al-Assad.

A War of Choice

Are we to admire Blair for his chutzpah or condemn him for his shamelessness? He calls to mind Philip II of Spain of whom was said: ‘No experience of the failure of his policy could shake his belief in its essential excellence’. Blair was widely ridiculed for his jaw-dropping claim, especially as Western intervention would effectively have been in support of the extremists. Syria’s military has been battling them with more fight and success than shown by Iraq’s army despite more than a decade of the best training that Coalition forces could provide.

George W. Bush, Tony Blair and John Howard took their countries to a war of choice to terminate Saddam Hussein, against the massive weight of popular, elite and global opinion. They insisted their judgment was superior and they would answer to history. It seems that history is giving its verdict and their nemesis is ISIS which has fought, tortured and killed its way through large swathes of Iraqi territory and captured many key towns. Against its ferocious onslaught the Iraqi military melted away faster than ice cream in the desert heat.

How do we impress on US neoconservatives and their fellow travellers the enormous disparity between the vision dreamed, the goals pursued, the means used and the results obtained? Eleven years later, conventional wisdom holds the war was one of the gravest foreign policy blunders of modern times. What remains inexplicable is why so many of the hawkish commentators who called it so disastrously wrong in 2003 continue to be darlings of the US media as expert commentators on the Middle East.

The Conflict’s Costs

Between 200,000 and one million Iraqis have died as a result of the war, including ‘excess deaths’ caused by degraded health facilities, the flight of doctors and reduced access to nutrition. The economic costs include almost two trillion dollars in federal government spending and double the amount when future health and disability payments for veterans are added. The war accelerated the military, financial and moral decline of America. The big strategic victor was Iran; in effect President Bush helped Iran to win its 1980–88 war with Iraq after a two-decade pause. The Middle East democracy project has suffered reverses; democracy cannot be imposed by bombers, helicopter gunships and tanks.

Saddam Hussein’s regime was the most secular in the whole region. His strongman rule was brutal but effective in imposing stability. His removal set off a train of pernicious consequences. It reduced the political space for secularists and promoted a hardening of zero-sum religious identity, which in turn sparked increasingly ruthless sectarian fighting that in a vicious cycle reinforced sectarian hatred. The poison of the hatred and killings seeped deep into Iraq’s body politic, as Nouri al-Maliki foolishly marginalised Sunnis from state structures and institutions, and then spread rapidly outwards to surrounding countries. By now it has engulfed the entire region with a deepening Sunni–Shia schism that sees Iran as the champion of the Shias and Saudi Arabia and Turkey as the two Sunni nodes. ISIS has been bankrolled by Saudi Wahhabi fundamentalists and other conservative Gulf States. They too must now fear blowback from the jihadist monster on the loose.

Future Prospects

President Barack Obama is right to be extremely circumspect about returning to the discredited and destabilising military option for resolving an internal Middle East crisis. Clearly US diplomats and soldiers will be protected. Beyond that, options range from doing nothing (on the reasoning that Washington no longer has a dog in the fight) to another full-fledged military intervention.

The first at least will have some support in US policy and commentariat circles; the last will have no support beyond the few who are yet to see a war they don’t like, learn nothing and forget everything. A Reuters-IPSOS public opinion poll published on 19 June showed a solid 55-20 majority against US intervention of any kind.

Options in between include drone strikes; military strikes by US planes and missiles stationed in the region; intelligence and logistical support for Iraqi government forces; cooperation with Iran against a common enemy; and acceptance of a tripartite split of Iraq into Shia, Sunni and Kurdish components rather than the nightmare of a united ‘Sunnistan’.

Meanwhile the crisis confirms the urgent need for parliamentary consent to be converted from an optional add-on to a legally binding requirement before a democracy goes to war. It should not be possible for a headstrong prime minister to wage war – the most solemn foreign policy decision of all – based on whims or personal convictions.

Ramesh Thakur is professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy.