The Buck Stops Where? Probing Duterte’s South China Sea Strategy in a New Light

The South China Sea dispute has been at the forefront of East Asian geopolitics. Unlike regional neighbours, the Philippines has employed a unique buck-passing strategy for managing the conflict.

This protracted conflict has stretched for several decades and altered the region’s security architecture significantly. Notably, the asymmetric distribution of power among the claimant states has substantially tilted the balance of power towards China. In response to such development, East Asian governments have mainly pursued either balancing or bandwagon tactics. While many observers and analysts have expansively discussed both schemes, a third approach is worth exploring: the Duterte administration’s buck-passing strategy in its dealings with China, and specifically those relating to the South China Sea dispute.

Underlying Strategies of Structural Realism and its Underlying Strategies

To understand the dynamics of international relations against the backdrop of power distribution, the theory of structural realism can best be applied. Structural realism assumes that the international system is anarchic due to the absence of a “world government.” Each state is hence expected to rely on its own to avoid the consequences of being conquered, coerced, or endangered. As such, they are forced to devise certain strategies to effectively ensure survival when clashes occur. In particular, states apply three different strategies, namely, balancing, bandwagoning, and buck-passing.

First, balancing occurs when a less powerful state aligns against a more powerful state. It involves actions taken by a particular state or a group of states to level the odds against a rival state. For instance, Vietnam has forged closer strategic relations with India by elevating their bilateral relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2016. Further, it granted Indian oil firm ONGC Videsh a two-year extension to explore oil block 128, which is a disputed area in the South China Sea. Indonesia has similarly bolstered its naval capabilities to effectively balance against China’s growing assertion in the disputed area. As of January 2020, it has deployed a total of eight warships in the Natuna area to enhance its patrolling capacity vis-a-vis Chinese boats.

Next, bandwagoning takes place when a less powerful state aligns with the more powerful State to guarantee its survival. Cambodia is an example as it has essentially gravitated toward China’s sphere of influence due to economic dependency. The 2012 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit ended without a joint statement for the first time because of Cambodia’s efforts to block any mention of the South China Sea dispute. Four years later, Cambodia remained adamant with its demand to make no reference to the international court ruling against China’s expansive claims. Brunei seems to have also jumped on the Chinese bandwagon, as it has ignored calls for a unified ASEAN response on the South China Sea situation. Brunei, too, is economically dependent on China.

Lastly, buck-passing refers to attributing a state’s responsibility to another state to deter or possibly confront an aggressive or more powerful state. Its role therefore becomes an active observer from the sidelines. John J. Mearsheimer noted that whenever a powerful or assertive state comes on the scene, one or more states will end up checking it. A state that uses the buck-passing strategy will initially get others to do the checking. Hence, this tactic “is essentially about who does the balancing, not whether it gets done.” More importantly, the process of buck-passing occurs where there is a multipolar system which entails that there are other capable powers that could balance against another powerful state. Accordingly, the Duterte administration’s position concerning the South China Sea dispute may be described as resembling such behaviour.

Buck-passing Personified: Exploring Duterte’s South China Sea Strategy towards China

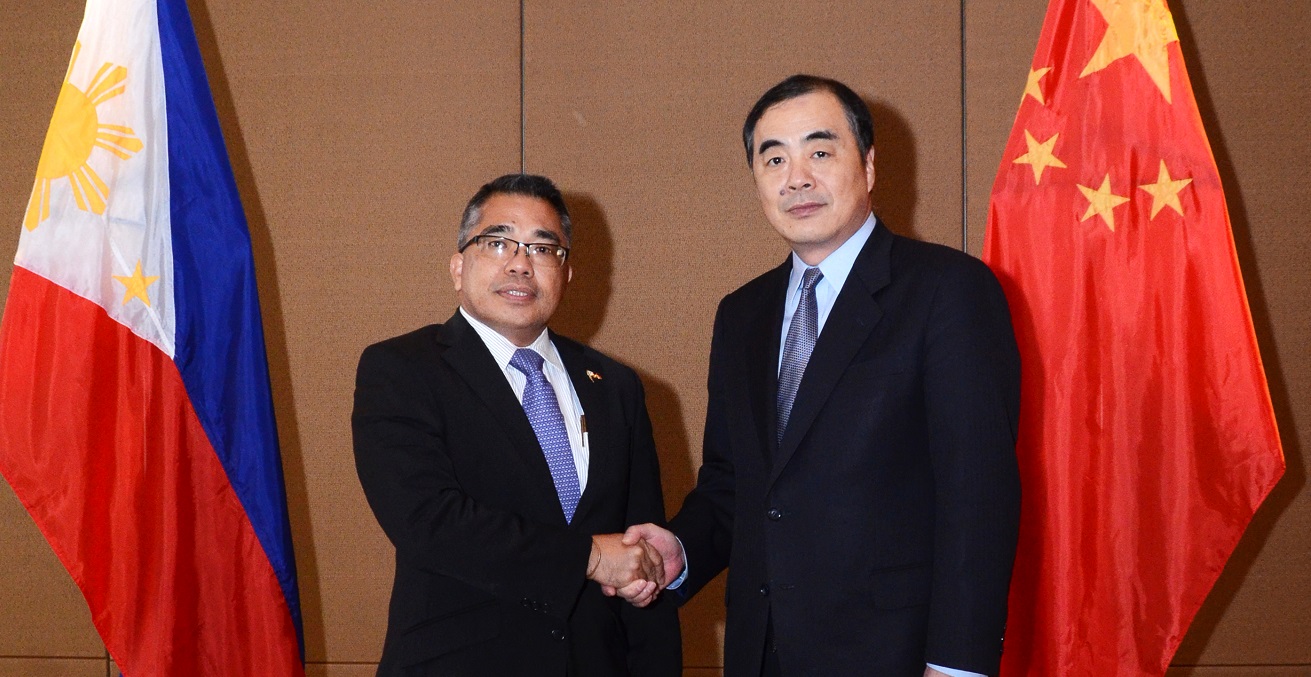

Since 2016, bilateral ties between the Philippines and China have been trending in a positive direction. Both states have agreed that a “sound” bilateral relationship contributes to “the fundamental interests of the two peoples.” For the Philippines, this move to cultivate a more diversified group of bilateral partners falls under the ambit of an independent foreign policy, which is pursued by the Duterte administration. Nevertheless, many sceptics question this pronouncement and speculate that the Philippine government is instead employing a bandwagon strategy. Several statements by President Duterte may be construed as confirming such perception but a handful of practical evidence prove otherwise.

First, the Philippine government has yet to officially sever its alliance with the US. This is despite President Duterte’s order in February 2020 to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement between both countries. During his visit to Manila in 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo explicitly clarified that any armed attack by China on Philippine military personnel or public vessels in the disputed South China Sea would automatically trigger Article 4 of the Mutual Defense Treaty. This signifies that the Philippines-U.S. relations may be better characterised as on the rocks, rather than dead in the water.

Second, symbolism matters. During a multilateral naval exercise in May 2019 in the contested waters of the South China Sea, the Philippines was represented by a patrol vessel which projects benign intentions towards China amid their South China Sea spat. Conversely, the US, Japan, and India utilised lethal and formidable naval vessels to demonstrate their commitment and willingness to preserving uninterrupted global trade More recently, the Philippines has expressed support and solidarity with Vietnam after the ramming and sinking of a Vietnamese fishing boat by a Chinese coast guard ship in the South China Sea. In response, the Philippine government lodged two diplomatic protests in April 2020 against China’s assertive actions.

Lastly, the Duterte administration is indeed applying a neutral rather than an independent foreign policy. For instance, the Philippine government has not reacted negatively against statements by the Quad and Vietnam regarding China’s assertive position in the South China Sea. This may be interpreted as a calculated move by the Duterte administration to maintain its strategic distance and to engage in the context of neutrality. Although the rhetoric does not match the practice, the Philippine government is likely well aware that China is a major challenger to its sovereignty and national interest.

Status Quo or Different Direction? The COVID-19 Pandemic as an Intervening Variable

With the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the security architecture of the South China Sea can be significantly altered. This scenario may bear positive results for the strategic calculations of the Duterte administration. China has proven to be an irresponsible actor by downplaying the threat posed by COVID-19 and suppressing information regarding the outbreak in its early stages. This has angered the international community as China’s actions have caused the loss of countless lives. This is a possible avenue for major states such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, and the US to engage more vigorously with China as an act of retribution.

In April 2020, the U.S. and Australia sent warships to the disputed territory to send a powerful message to China regarding the latter’s growing assertion in the South China Sea. This may be the start of a new trend in the disputed region and may be the answer to the question of where the buck would stop. China’s steady uncontested rise, coupled with the devastating effects of the pandemic, may be enough to create a more formidable balancing coalition against it. If successful, the balancing coalition would significantly deter China’s growing assertion specifically in the South China Sea and would reap positive results for the Duterte administration’s strategy of buck-passing. However, if no significant balancing effort is made, the Philippines must reconsider its strategic options to serve its interests in the South China Sea.

Don McLain Gill is currently pursuing his master’s degree in International Studies in the University of the Philippines Diliman. He has written on regional geopolitics and traditional security issues in the Indo-Pacific.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.