The ANZACs in the Pacific - Myths in Empire

The centenary of the Gallipoli landings prompted national introspection about the “myth” of the strong, brave and irreverent Aussie soldier. But closer to home, in the Pacific, the myth unravelled.

Though the dominant focus of the Great War for Australia and New Zealand has been Gallipoli and the Western Front, for both nations World War One began in September 1914 far closer to home. For New Zealand, it began in Samoa. For Australia it began in New Guinea (Australian forces would later secure the lucrative phosphate island of Nauru for the Empire). The British dominions occupied German colonies, knocking out communications systems for German forces in the Asia Pacific and then stripping the belligerent nation of its colonies. During the war Samoa and New Guinea were under New Zealand and Australia military occupation. These occupations left deep scars and damaged national reputations. New Zealand was held accountable for the disastrous influenza epidemic that struck the islands in November 1918, killing over 20% of the population in a matter of weeks. Australia’s military occupation was dogged by accusations of endemic brutality towards New Guineans that even Australian authorities, inured to frontier violence in Australia, acknowledged and pledged to improve.

When the guns of World War One fell silent on 11 November 1918, the reckoning and aftermath of the war began. For Australia and New Zealand, the new white nations in the Pacific, the staggering losses of the Great War wrenched these British dominions into new shapes. The myriad of war experiences for both countries was refracted through the newly forged myth of ANZAC. The myth grew exponentially after the war’s end and came to encompass far more than the eight-month experience in the Gallipoli campaign. Returned soldiers were gilded by this myth. They assumed a superhuman status; exemplars of white manhood.

Once the war was over, the international community gathered in Paris to reconstruct the world order, which entailed determining the future of the former German colonies. In these discussions the League of Nations was born, as was one of its components, the Permanent Mandates Commission (PMC). The PMC would oversee the governance of these former German colonies. Australia and New Zealand’s military occupations became League of Nations ‘mandates’ on 1 January 1921 and supposedly a new era of civilian rule commenced. They also shared the administration of the Mandate of Nauru with Britain.

The end of the Great War in Europe meant a colonial surge in the Pacific as men – many of them ANZACs – highly trained, equipped with the latest military hardware and deeply scarred by the hyper-violence of the Great War took over these colonies. Not only was this war experience a critical factor in what happened in the Pacific mandates. These ANZACs, who were now colonial personnel from the top of the administrations down, also brought the deeper and troubled history of relations between Indigenous Australians and Māori, with them to the Pacific Mandates.

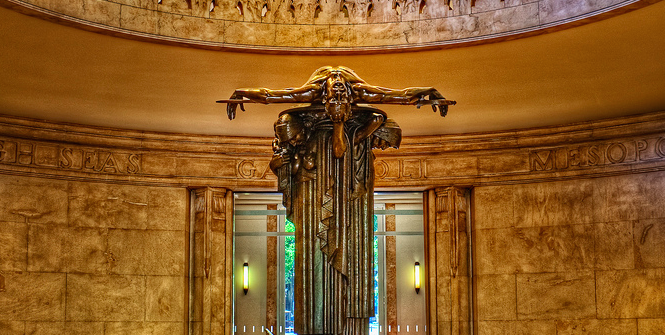

The ANZAC myth stresses heroism, sacrifice and mateship. The myth was exemplified artistically by Rayner Hoff’s 1928 sculpture ‘Sacrifice’, the centrepiece for Sydney’s War Memorial. Here was manhood in its most perfect and purest form, the beautiful dead, the flower of Australia’s and New Zealand’s youth. A plethora of other representations of the myth have spanned the century since 1915, at every war memorial dotted around both countries and in so many other ways. But what happens to the ANZAC myth, this iconic image of gilded masculinity, when we consider the part played by ANZACs in the postwar colonial surge in the Pacific?

Both nations saw their roles in New Guinea and Samoa as doing their ‘white man’s burden’, their imperial duty. The League of Nations covenant described the role of the mandatory powers as ‘a sacred trust’ towards the people under their care. This gloss however had new complications that undercut the colonial mission entirely. This was thanks to Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, particularly ‘point five’. This point pledged that the interests of populations living under ‘colonial claims’ would be given ‘equal weight’ to those of colonial powers. This was a statement that electrified people living in colonies. They interpreted this as Wilson’s desire to see self-government for colonised people across the globe, though the real intention was light years away from this. Wilson, the League and colonial powers envisaged quite different outcomes. Colonial powers still saw the colonial system as perpetual, so strongly did they adhere to notions of racial hierarchies that underpinned the colonial system.

This great clash of expectations thrust Australia and New Zealand into the midst of the global crisis of empire that erupted after the end of the Great War. The prestige of the white race was under siege, and colonial populations became increasingly difficult to govern.

Samoa was unified by a common culture, and language and literacy levels were high. In this environment ideas quickly spread about self-government conflicting with a rapidly imposed paternalistic regime from 1921, when the mandate era came into force. As a result the protest movement, the Mau, bedevilled New Zealand’s administration of Samoa and its postwar international reputation. Though the Mau against New Zealand existed from 1921, it was solidified in late 1926 when protests and the administration’s draconian responses to them entered a new level of intensity.

New Guinea was a vastly different colonial entity to Samoa. It drew together enormously disparate peoples – linguistically and geographically – into one governing unit. Some areas of New Guinea by the 1920s, had not even encountered Europeans. Australia’s governance of its mandated territory improved little from the disgraceful wartime occupation once the mandate era commenced. Matters deteriorated from late 1926 when gold was discovered, bringing legions of white men, many of whom were ex-soldiers, to prospect and hopefully become enriched on New Guinea diggings. Cycles of violence that had marred previous Australian frontiers erupted. Violations of local women and misunderstandings about custom and law were followed by reprisal attacks by local people on white men that, in turn, were pursued by colonial punitive expeditions meting out collective punishment on local communities. The men carrying out these punitive expeditions, as they did in the Nakanai area of New Britain, in late 1926, were ex-soldiers. They used a machine gun, grenades and World War One experience against men armed with spears. When news of this reached the papers, the Australian government tried to deny anything of this nature had taken place. Once overwhelming evidence was presented that contradicted their assertions, the government, with the sympathetic press, emphasised the punitive expedition was avenging the lives of four ANZACs, and so it was somehow justified.

Three years later, on the streets of Apia, New Zealand ex-WWI machine gunners and sharp shooters opened fire on a peaceful protest of Mau supporters in what became known as the ‘Black Saturday Massacre’. Like Australia in 1926, the New Zealand government tried to hose down the ensuing controversy once news got out. They cited provocation by the Samoans as a way to explain this seemingly gross breach of their ‘sacred trust’ towards the people they governed under the mandate system. Again, evoking the ANZAC myth and war experience was used to detract from the killings of nine Samoans.

In New Guinea and Samoa, ANZAC mythology acquired a new and overlooked dimension. Here it was a tool applied in fraught colonial situations, to justify subjugating Pacific peoples. The ANZAC myth operated in many other ways in New Zealand and Australia’s Pacific mandates. Perhaps, now that the centenary of Gallipoli has passed, it may be time to look at the wider implications of ANZAC mythology and the actions of ANZACs in the Pacific. Though deeply uncomfortable, we need to acknowledge the connection between the Great War and the colonial surge in the Pacific that, like Gallipoli, resonates into the present day.

Patricia O’Brien is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow, School of History, RSSS, CASS, Australian National University. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.