Fifty Years Since the Tet Offensive

Fifty years ago this week, a series of attacks by North Vietnamese forces on the eve of New Year celebrations marked a turning point in the Vietnam War. The offensive transformed America’s previously optimistic perceptions.

The Tet Offensive of 30 January 1968 erupted throughout the Republic of Vietnam when more than 80,000 enemy troops assaulted 36 of the Republic’s 44 provincial capitals and 64 of its 242 district capitals. Five of the country’s six autonomous cities were attacked. Major military and air bases such as Tan Son Nhut and Bien Hoa were attacked while others were hit by rocket and mortar fire. In Hue the enemy forces waged a determined resistance, finally being driven out of the old imperial capital after a month of bitter fighting.

The Central Military Party Committee of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam began planning a strategic offensive in April 1967. It was believed that a decisive military victory could be achieved by launching simultaneous surprise attacks on Saigon, Hue and Da Nang plus attacks on most of South Vietnam’s province capitals, autonomous cities and some military bases and major regional villages. It was expected that the surprise attack combined with a general uprising of the people would bring victory. Throughout 1967, training, organisational and logistics preparations intensified in North Vietnam, along the Ho Chi Minh trail and clandestinely within the target cities and villages.

In October 1967, the Politburo decided that the general offensive would be launched during the traditional Tet holiday period in January-February 1968. Tet was a sacred holiday in the Vietnamese calendar. People travelled the country to be with their families for the festivities. A ceasefire was negotiated in recognition of the significance of the holiday and soldiers from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) took leave from their units to be with family. The movement of people and preparations for the festivities masked the movement of the Viet Cong and People’s Army assault forces into their attack positions.

Enemy preparations did not go entirely unnoticed by the US military and its South Vietnamese allies. Although specific targets and timings were unknown, by mid-January 1968 various indicators suggested that the Viet Cong would launch a major offensive against objectives in heavily populated areas. Adapting to this threat, the US command in Vietnam bolstered its forces near the centres of civilian population. The Tet holiday ceasefire was cancelled on 30 January, but due to poor communications within the South Vietnamese army many of their units remained at about 50 per cent strength when the offensive struck the following day.

Militarily, the offensive was a failure. The Viet Cong and People’s Army suffered massive losses. The general uprising had failed to materialise. The trashing of the sacred Tet holiday and the breach of the ceasefire incensed many of the Republic’s citizens. There was a surge in volunteers for military service in the South’s armed forces and the South Vietnamese army had performed much better than expected. The strategic and psychological effects of the offensive were more significant than the enemy’s temporary military achievements. An attack on the US embassy in Saigon, though all 19 of the enemy troops were killed or captured before they could get into the building, seemed to shock Americans. A wave of pessimism swept through the American public and political support for the campaign waned.

In the Australian area of operations in Phuoc Tuy Province, southeast of Saigon, the enemy assault fell on the province capital, Baria, at 5am on 1 February. Baria was a substantial town of more than 18,000 people. The enemy’s D445 battalion and Chau Duc District Company swept into the town from the north and west. They met solid resistance from local South Vietnamese security forces and, at 8.30am, an Australian rifle company mounted in armoured personnel carriers counterattacked, breaking the Viet Cong hold on the key positions and, with ARVN support, ejected the enemy from the town by nightfall that day. The fight then shifted to Long Dien village.

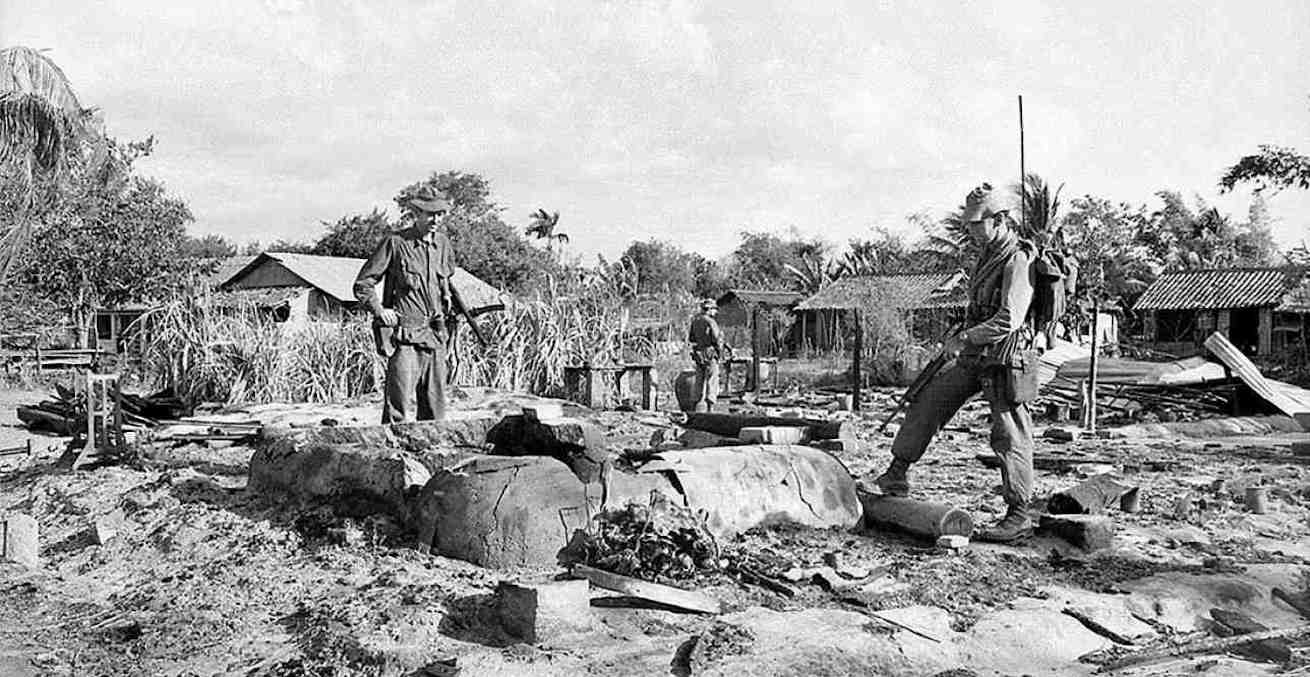

Long Dien, five kilometres east of the capital, was a substantial village with a population of over 15,000. It rivalled Baria as the commercial hub of the province. The fighting in Long Dien lasted four days and there was evidence that civilians supported the Viet Cong by pointing out the residences of village officials and hiding the Viet Cong soldiers from the searching Australian and South Vietnamese forces.

Civilian casualties in Phuoc Tuy Province during the Tet Offensive were 67 killed and 106 wounded. In Baria, about 60 buildings were totally destroyed, with more than 100 seriously damaged. The struggle in Long Dien resulted in 28 buildings destroyed and nearly 100 damaged.

Following the Tet Offensive battles, 1 Australian Civil Affairs Unit (1ACAU) initiated a program to re-house those families made homeless. Nearly 140 houses were built in Long Dien district with the program ending in early August 1968. A further 26 houses were built in Baria. The commander of the Australian forces in Vietnam conceded that there was “almost certainly some psychological advantage to the VC because of the battles in Baria and Long Dien”. But in the longer term this psychological advantage may have been moderated by the efforts of the Australian Civil Affairs Unit. A report of the re-housing program noted:

This military Civic Action Project has attracted both written and verbal statements of appreciation from the local officials and villagers. More importantly, it has enhanced the Australian Army image in what was previously a hostile community at Long Dien. As such it may be considered a successful exercise although any long-term effort is difficult to assess in view of the continuing marginal situation which exists in and around Long Dien.

Following the battles of Tet 1968 some of the province’s citizens continued to provide political and financial support, intelligence and supplies to the Viet Cong. Enemy units continued to make night-time penetrations into the villages on a regular basis and support for the Viet Cong did not vary significantly as a result of these urban operations. While local support for the Australian forces might have improved, it did not do so decisively.

To learn more about the Tet Offensive in Phuoc Tuy Province, visit the Australia’s Vietnam War website.

Dr Bob Hall is a lecturer at the UNSW Canberra in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.

The image shows Australian troops examining the ashes and rubble in Long Dien in February 1968. (Source: Department of Veterans’ Affairs)