Strategic Competition and the Evolving Role of Indo-Pacific Paradiplomacy

Many of the drivers of paradiplomacy, such as the search for foreign direct investment, remain the same. New factors, in the form of strategic competition, are emerging and influencing the ways in which subnational actors interact with each other and with other countries.

In October 2018 the Australian state of Victoria signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Beijing, joining the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A year later, a new agreement was penned, further deepening Victoria’s engagement with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The agreements promoted Chinese investment and participation in Victorian infrastructure projects. Victoria’s Labor premier, Daniel Andrews, proclaimed the agreement as good for Victorian workers and expressed his hope that “every state and territory, and indeed the Commonwealth, would have a strong partnership and friendship with China.”

On 24 May 2020, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seemingly threatened the Australian-American alliance over Victoria’s actions. He said that while he was unfamiliar with the details of Victoria’s agreement, should the Victoria-PRC arrangement threaten the security of defence and intelligence telecommunications networks, the US “will simply disconnect.” Pompeo has not been the only voice criticising Victoria’s signing on to the BRI. In 2019, Australia’s Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton, called the deal a “rushed decision.” Michael Shoebridge, a national security analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, went further, labelling the Victoria BRI initiative a “zombie project” that needs to be “halted and comprehensively reassessed.” He called into question the role of states in pursuing international agreements, especially with regard to China.

Though subnational entities in the international environment are a given, experts wondered how Australia could better orchestrate state and commonwealth interests. For example, a state like Queensland should have its own foreign policy, albeit not at the expense of a national foreign policy. On August 26, 2020, the Australian federal government announced plans to review all international agreements proposed by the states.

The Victorian example highlights one of the dynamics of change in the strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific and the evolving character of subnational relations, or paradiplomacy, in the region. While new drivers of regional paradiplomacy are emerging, they build upon already existing forms of subnational activity.

Strategic competition

In 2017 the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) labelled China as a revisionist state and a strategic competitor. China, the NSS declared, seeks to “challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity.” Then in 2019, the then Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan in his introduction to the US Indo-Pacific Strategy Report claimed that China “seeks to reorder the region to its advantage by leveraging military modernization, influence operations, and predatory economics to coerce other nations.”

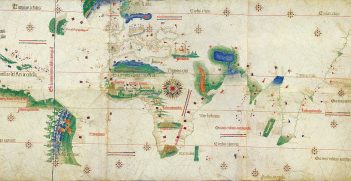

One element in China’s search for revision is the BRI. A stated goal of the BRI is to recreate the Silk Road, through the development of infrastructure (e.g. road, bridges, and ports), funded by loans and grants from the PRC. While the initial impulse for the BRI might well have been to manage China’s excess manufacturing capacity, it has over time become more than that. For example, some argue that the BRI will draw surrounding countries into China’s orbit of influence and extend Beijing’s strategic, political, and economic interests. Therefore, for some observers, the BRI is an essential part of Beijing’s revisionist goals.

One aspect of the BRI of particular interest is the role played by subnational entities in advancing Beijing’s interests. The Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) began in 2015 a series of lectures to explore the ways in which people-to-people diplomacy could promote the BRI. The CPAFFC is one of several Chinese agencies responsible for foreign influence operations and handles sister city relationships. In these arrangements, subnational governments become important players in Beijing’s quest for establishing and growing the BRI, and by extension China’s revisionist strategic goals.

Paradiplomacy

Paradiplomacy concerns the international activities of subnational actors, such as states, provinces, regions, local governments, and cities. Interest in subnational actors in the international system found early favour in light of Quebec’s independence campaign and Richard Nixon’s new federalism. The term paradiplomacy, first coined in 1961 by Rohan Butler, refers to the international activities of subnational actors that operate in parallel with the nation-state. Not all paradiplomacy concerns subnational actor-to-subnational actor relations. In many instances, subnational actors may interact with nation-states, or nation-states may seek out a subnational entity.

Paradiplomacy has long played an important role in pursuit of foreign direct investment and markets, and since at least the mid-1950s, subnational actors have canvased the globe in a competitive search dollars and customers. One way in which subnational actors seek to institutionalise relationships is through sister-state or sister-city relationships. These sister relationships can help stabilise communication and investment networks. Australian states, for example, have at least 30 sister-state relationships, most of which are in the Indo-Pacific. Australia also has hundreds of robust sister-city relationships, including 90 with China with 90. The process by which such relationships are formed reflect the governmental environment in which they take place.

The future course of paradiplomacy and strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific

The future course of paradiplomacy and strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific will be influenced by four factors: the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, adaptations and revisions to the BRI, responding to less friendly national governments in the region, and leaders of subnational governments using paradiplomacy to further their own interests.

The economic fallout of the COVID pandemic will drive the search for FDI and markets. The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects outlines the potential consequences of the COVID pandemic for the globe. A 5.2 percent contraction of global GDP is forecast, and “likely to leave lasting scars through multiple channels, including lower investment; erosion of the human capital of the unemployed; and a retreat from global trade and supply linkages.” The economic forecasts are dire for the Indo-Pacific region. These forecasts underscore the necessity of finding FDI and accessing export markets, and paradiplomacy will continue to play a role here.

A second factor concerns adaptations in the BRI. The BRI has been variously described as predatory economics, loan-to-own finance, debt-trap-diplomacy, and the use of economic tools resulting in geostrategic gains. In reply to such criticisms, Beijing has undertaken a number of steps suggestive of enhanced paradiplomacy. In August 2018 Beijing hosted a workshop the focus of which largely concerned BRI adaptations. Xi urged that the BRI “align more systematically with the needs of local countries” and emphasised that projects must encourage “local popular support for the BRI.” The emphasis on the local reinforces the centrality of paradiplomacy to the BRI’s planned success.

The third factor to play out concerns the ways in which the PRC can marshal subnational US state governments as a hedge against an unfriendly federal government in Washington. The Chinese government spends a lot of time trying to influence state and local politics through people-to-people connections.

Finally, paradiplomacy will continue to be used by subnational leaders a way of countering national government policies. In Australia, Victorian premier Daniel Andrews signalled that signing on to the BRI was not only good for Victoria but might also foster a closer relationship between Canberra and Beijing. Australia’s proposed changes to the way state governments operate in the international environment may, however, be constrain subnational governments when it comes to strategic competition. Of course, in Australia more scope exists for the federal government to limit the activities of the states, whereas US constitutional protections make such limitations less likely. Practically speaking, such constraints on the paradiplomacy of local entities seeking FDI and trade opportunities may run counter to the economic drivers emerging as a result of the impacts of COVID-19.

Paradiplomacy and strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific bring the subnational and international together. China’s BRI necessitates close cooperation with subnational governments. Similarly, economic necessity also brings local, state and regional governments into the international environment in search of FDI and markets. Regulating and managing these relationships will test the legislative and constitutional powers of countries. Ironically, the story of strategic competition between great powers may play out, not in the competitive fields between nation states, but rather in the backwaters of local governments.

Alan Tidwell is Professor and Director of the Center for Australian, New Zealand and Pacific Studies at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

This is an extract of Tidwell’s article in the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled, “Strategic competition and the evolving role of Indo-Pacific paradiplomacy.” It is republished with permission.