Shaping Australia’s Nuclear Policies

With a change of government likely in May 2019, will Australia reclaim a leadership role in global arms control efforts? The Australian Labor Party’s National Conference will give some clues.

Australia’s current nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation policies were largely shaped by three issues: commercial interest in exporting uranium, opposition to French nuclear testing in the Pacific; and the nuclear umbrella implicit in Australia’s alliance with the United States.

Australia’s nuclear policies have mostly enjoyed support from both sides of the domestic political divide. However, there has been a different emphasis and a greater commitment to activism by the Australian Labor Party (ALP).

In 1973 the new ALP government put a decisive end to two decades of nuclear weapons hedging by ratifying the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It also initiated an enquiry into proposals to start exploiting the recently-discovered vast uranium resources in Northern Australia.

Out of government from 1975 till 1983, the ALP was deeply divided over uranium mining, with tensions aggravated by continued French nuclear testing. A compromise was finally reached at the 1984 ALP National Conference: uranium mining would be permitted at a limited number of mines under strict environmental conditions and the export of uranium would be subject to strengthened safeguards. Furthermore, the government committed to greater international activism, including negotiation of a South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone.

Successive ALP governments have upheld Australia’s leadership in multilateral arms control negotiations, playing a leading role in the successful conclusion of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention, and in strengthening the non-proliferation regime, creating the Australia Group to ensure exports do not contribute to the development of chemical or biological weapons. They commissioned authoritative reports to guide global arms control efforts: the 1996 report of the Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons and the 2009 Report of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND), a joint project of Australia and Japan.

Considering this background and subsequent policy statements of the ALP while in opposition, it can be expected that with the likely change of government in May 2019, Australia will reclaim a leadership role in global arms control efforts.

However, the ALP’s nuclear policies have again become an issue within the party. In 2011, the ALP National Conference voted 206 to 185 to allow an exception for sales to India, despite it not being a party to the NPT. In the wake of the extravagant claims made by the proponents of the India deal, the absence of any commercial sales suggests that principle was abandoned for no apparent gain.

The upcoming ALP National Conference on 16-18 December will be faced with another contentious nuclear issue: whether Australia should join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (Nuclear Ban Treaty).

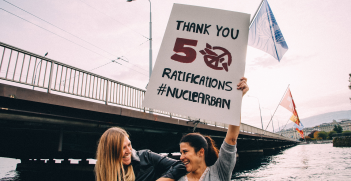

Negotiated in 2017, the Nuclear Ban Treaty is the culmination of several years of agitation by governments angered by the absence of progress in nuclear disarmament. The initiative had strong support from non-governmental organisations such as the Australia-founded, Nobel Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). The treaty has been ratified by 19 countries but 50 are needed to bring it into force.

A majority of shadow cabinet has signed the ICAN Parliamentary Pledge to support joining the Nuclear Ban Treaty. However the draft ALP National Platform 2018 to be considered by the National Conference, while lauding ICAN and avoiding outright rejection of the Nuclear Ban Treaty, calls rather for “the development of a time-bound framework to negotiate practical, legally binding agreements” to achieve its aspirations.

Just as important, at the Australian Institute of International Affairs’ National Conference in October, the likely next foreign minister, Senator Penny Wong, addressed the issue at length. She argued that while she agreed with the objective of the treaty, it suffered three substantive shortcomings: lack of universality, shortcomings on verification and security.

The speech chides the government for not participating in the TPNW negotiation, and thereby securing a better outcome. However even if Australia had been joined by all the 30-plus US-allied nuclear umbrella states not participating in the negotiation, it would have resulted in an even more poisonous split between allied and non-allied supporters of the NPT: a hiding to nothing as the Netherlands learned as the only NATO ally that did participate.

Of the three shortcomings, two are compelling. First, the lack of participation, indeed hostility, of the states with nuclear weapons is a fatal flaw. It is only when the political-security conditions are right that it will be possible to reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons stockpiles.

Equally compelling is the consideration that the Nuclear Ban Treaty is incompatible with Australia’s reliance on the United States’ nuclear umbrella. Ultimately, ALP-led governments will acknowledge and protect that relationship, moderated by occasional assertions of differences. While a decision not to sign the Nuclear Ban Treaty will be welcome in Washington, the US will still be irritated by the expressions of sympathy for the normative objective of the treaty.

Senator Wong’s commitment to building the capacity of the international safeguards system is very welcome. However, it is a distraction to argue that the Nuclear Ban Treaty undermines international safeguards by not requiring parties to adopt best-practice Additional Protocol verification. Australia and others have been urging universal acceptance of the Additional Protocol since its adoption 20 years ago. But several states have resolutely resisted. Had the Nuclear Ban Treaty included such a requirement these hold out states would not have agreed to the treaty and its normative impact would have been further diminished.

The advocates of the Nuclear Ban Treaty argue the treaty closes a gap in the bans on weapons of mass destruction: chemical and biological weapons had been long proscribed and now nuclear weapons are banned. This is dangerously deceptive. Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, large quantities of chemical weapons have been destroyed. There is no prospect of even one nuclear weapon being dismantled in the name of the Nuclear Ban Treaty. Efforts being devoted to securing new members of the Nuclear Ban Treaty simply distract from the practical measures that could over time help create the conditions necessary for nuclear disarmament.

Unfortunately, the ALP’s policy agenda for practical measures is disappointing. Universal no first use declarations, stockpile reductions and a cut-off treaty are all very worthy objectives but have been under discussion for decades. The nuclear disarmament log-jam has to be overcome by directly tackling the nuclear deterrence dyads and triads. Deeper engagement on nuclear issues in the Indo-Pacific should be the starting point. Australia’s alliance with the United States should be invoked to secure urgent evidence of good intent on nuclear disarmament to bolster the NPT as it approaches its 50th anniversary. Australia should work with our regional partners on options for supporting a denuclearised Korean Peninsula. Leveraging Australia’s nuclear cooperation agreement with India, and the admission of India earlier this year to the Australia Group, Australia could work with others to strengthen nuclear security in South Asia.

The forthcoming ALP National Conference will reflect the party’s fitness for government. The leadership will therefore be keen to avoid a recurrence of the divisive debates of the past on nuclear issues. The course mapped out by Senator Wong, based on the ICNND report, is the sensible middle path. The requirement now is for a reinvigorated action agenda supported by high-level political leadership and expanded diplomatic activity. Labor governments have provided the necessary leadership and resources in the past and must do so again.

John Tilemann is a former career diplomat with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.