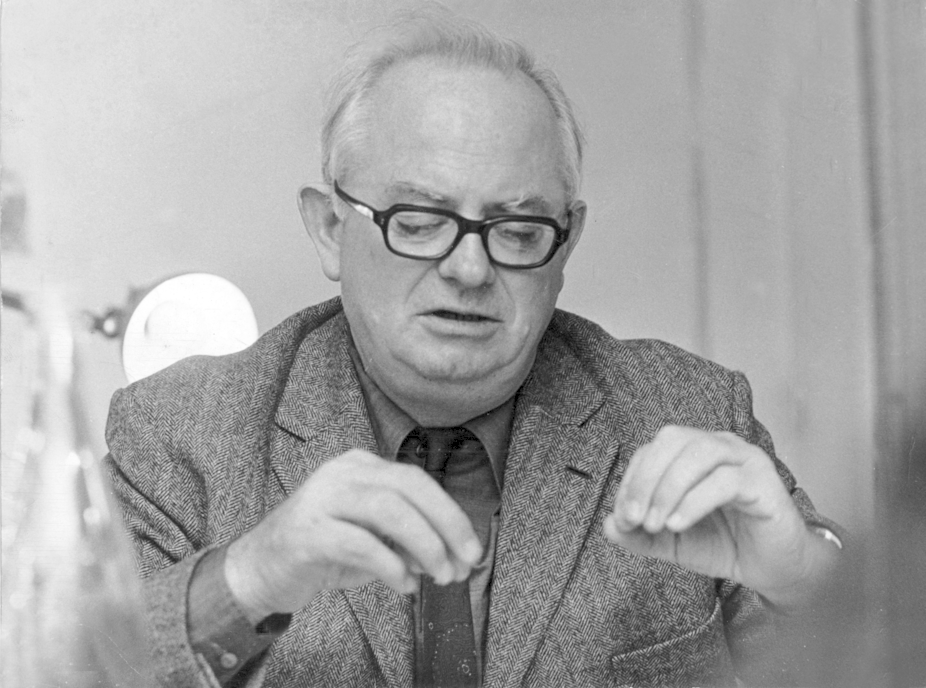

Seventy Years After Hiroshima, Who Was Australian War Correspondent Wilfred Burchett?

Seventy years ago, on September 5, 1945, Wilfred Burchett’s report on the aftermath of the Hiroshima atomic bombing was published in London’s Daily Express. Burchett was the first Western journalist to enter Hiroshima after the bombing and was shocked by the devastation.

Under the banner “I write this as a warning to the world”, Burchett described a city reduced to “reddish rubble” and people dying from an unknown “atomic plague”.

Burchett’s report has been dubbed the “scoop of the century”. At the time it was ignored by most Western newspapers and dismissed as pro-Japanese propaganda. The story is now considered his finest. In October 2014, it earned him a place in the Victorian Media Hall of Fame, but the decision was not universally applauded.

Groundbreaking reporting on Korea

Though Burchett cut his journalistic teeth with the Express, he built his reputation covering the Korean and Vietnam wars from behind the communist lines. For this, Burchett was dismissed as a communist propagandist and traitor, though few know the real story.

In Korea, Burchett accused the American-led United Nations’ forces of prison camp atrocities and waging bacteriological warfare. The latter was Burchett’s most controversial story and has since been supported by a 2010 al-Jazeera report. But it sullied Burchett’s reputation in the West and angered the US military establishment.

Burchett had seen remnants of germ warfare attacks. He had interviewed captured American fliers who had confessed to Chinese interrogators to conducting germ warfare raids. He had also assisted the World Peace Council’s International Scientific Commission’s investigation, which backed the North Korean and Chinese allegations.

Attempting to “kill” the story, the US military’s Far Eastern Command (FEC) asked the Menzies government in Australia for permission to “exfiltrate” Burchett from North Korea in September 1953. The government refused, fearing an electoral backlash if Burchett suddenly appeared on Australia’s doorstep. FEC persisted with a US$100,000 enticement, but Burchett was not for sale.

Meanwhile, the Australian government investigated the possibility of charging Burchett with treason. ASIO agents were despatched to Japan and Korea to collect evidence, but their investigations uncovered little. In early 1954, the government conceded there was no hope of prosecuting Burchett.

To deter him from returning to Australia, the government publicly kept open the prospect of prosecution while privately acknowledging it had little chance of success. It found a willing ally in FEC. Concerned about Burchett’s reports from Indochina, FEC asked the Menzies government for permission to discredit the journalist.

Consequently, Burchett was subjected to government-backed smear campaigns and barred from Australia. Repeated requests for the restoration of his Australian passport were refused. According to the then-immigration minister, Harold Holt, Burchett had “severed all connection with Australia” because of his “activities” abroad.

Changing views

The Vietnam War altered Western views of Burchett.

Burchett had access to the North Vietnamese leadership and the South’s National Liberation Front. On requests from the British and US, he attempted to persuade Hanoi to release captured American airmen. His 1967 interview with the North Vietnamese foreign minister, Nguyen Duy Trinh, was considered one of the “scoops” of the war. It was the first inkling that Hanoi was willing to entertain peace talks.

When talks commenced in Paris in mid-1968, Burchett was courted by the US delegation’s chief negotiator, Averell Harriman. For his assistance, he was granted entry to Britain and the US. He even breakfasted with the US national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, at the White House.

But Burchett was still unwelcome in Australia. Fearing he might return, the Liberal prime minister, John Gorton, warned ministers against criticising the journalist outside the parliament. Recognising the flimsy nature of the case against Burchett, the government wanted to avoid being sued for defamation.

Burchett finally returned in early 1970 on a privately chartered light plane. The Gorton government had threatened airlines with steep penalties for flying Burchett into the country.

With the Whitlam Labor government’s election in December 1972, Burchett’s passport was restored. As Whitlam explained, there was no evidence to justify its continued denial.

Defamed and exiled

Rumours persisted that Burchett was on numerous communist governments’ payrolls. The most damaging came from the Soviet defector, Yuri Krotkov. He and Burchett had met in Berlin after the war. They renewed acquaintances when Burchett moved to Moscow in 1957.

Krotkov defected to Britain in the early 1960s claiming to be a KGB agent. In reality, he was a minnow attached to a KGB prostitution ring, specialising in diplomatic honey-traps. MI5 dismissively off-loaded him to the Americans, and in 1967 he appeared before the McCarthy-ridden US Senate Sub-committee on Internal Security where he alleged Burchett was a KGB agent and on China’s payroll during the Korean War.

An account of Krotkov’s testimony was published in the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) pamphlet, Focus, in November 1971 and tabled in the Australian Senate. In February 1973 Burchett issued a writ for defamation against Focus’ publisher, DLP senator Jack Kane.

The case was heard in the NSW Supreme Court in October 1974. Though strapped for funds, Kane’s case was well supported. The chairman of the Herald & Weekly Times, Sir Philip Jones, lent his backing, as did Menzies. ASIO assisted with the names of Australian POWs whom Burchett had met in Korea, while Australia’s military chiefs-of-staff took the stand on Kane’s behalf.

Even Kissinger kept an eye on the case. He and the American ambassador to Australia, Marshall Green, feared the trial could re-ignite allegations that the US had deployed germ warfare in Korea.

For two weeks Burchett’s reputation was butchered in the box and mainstream press. Despite this, the court found he had been defamed. As the article had been tabled in the Senate, it was protected by parliamentary privilege. Burchett won the case but costs were awarded against him, forcing him into financial exile.

Debates over legacy persist

Though he died in 1983, Burchett remains a controversial figure. Rumours persist of Burchett’s alleged KGB recruitment. In 2013, academic Robert Manne claimed to have proof of Burchett’s KGB links. Drawing on a document uncovered by Russian dissident Vladimir Bukovsky, Manne asserted that Burchett was put on the KGB payroll in July 1957.

No evidence was produced to show Burchett pocketed KGB money. If he did, the KGB got short-changed. By the early 1960s Burchett had wearied of Soviet communism and sided with the Chinese during Sino-Soviet split. He even worried that Soviet authorities were tampering with his Moscow mail.

Rumours of Burchett’s alleged treacheries still persist. They are part of Australian Cold War folklore and seem to have influenced the Hall of Fame’s decision to support Burchett’s inclusion principally on his Hiroshima story.

Burchett wrote stories that the Australian and US governments preferred not to be told and paid the price. He covered wars in which Australians fought on the other side. He was not “a my country right or wrong” barracker, but reported the facts as he saw them, and for the most part got them right. His career should be judged on all his achievements and not reduced to a solitary story.

Lecturer at the National Centre for Australian Studies, Faculty of Arts at Monash University. This article was originally published in The Conversation on 4 September 2015. It is republished with permission.