The Scourge of Sexual Violence in Myanmar

Addressing sexual violence is not a negotiable condition for achieving peace. With more information on the location of crimes and the perpetrators, we can use data and knowledge on patterns of reporting to intervene.

“The international community, especially the UN Security Council, has failed us. This latest crisis should have been prevented if the warning signs since 2012 had not been ignored,” said Razia Sultana, a Rohingya rights lawyer and civil society representative.

What are the early warning signs of sexual violence in armed conflict (SVAC) in conflicts with different levels of intensity? There is a large volume of research on sexual violence in wars, particularly within Sub-Saharan Africa and increasingly the Middle East. But our knowledge is relatively limited when it comes to understanding incidence and reporting conditions in the protracted conflicts that often experience waves of ‘low-level’ violence over many years, coupled with short episodes of intense violence – such as Myanmar.

We have compiled the new PSVAP (Preventing Mass Sexual Violence in Asia-Pacific) dataset of all existing reports of types of sexual violence and gender-based violence by official, unofficial and media organisations to explore the patterns of reporting and of reported violence in three active conflict environments: the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

We wanted to see how far and in what ways this reported (not necessarily verified) violence matched our assumptions based on existing research studies about ‘where’ conflict-related sexual violence occurs, ‘who’ perpetrates it, and ‘when’ it is used as a weapon.

Conflict in these locations is protracted and can shift across the spectrum from high intensity to low intensity in the space of a year. Accordingly, we wanted to test the ideas that such violence rarely occurs in ‘low intensity’ conflict environments, and that the reports may be the mere ‘tip of the iceberg’ of conflict-related sexual violence.

To do this, we complemented our PSVAP dataset with our field research data from talking to key international, government, humanitarian, human rights and women’s rights organisations working in conflict situations.

Based on this, we could have predicted the sexual violence perpetrated against Myanmar’s Rohingya people in 2017: our 1998-2016 dataset reveals that sexual violence often occurs just before and during periods of heightened conflict intensity.

The rise in SVAC reports revealed in the dataset does not mean its incidence is also increasing. Rather, with Myanmar’s democratic transition we are seeing increased freedom to report and a greater presence of non-governmental and international actors on the ground. This statement is not controversial – but to leave it at that would be problematic.

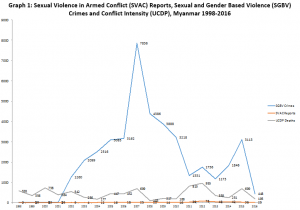

It is important to pay attention to what is being reported (how many incidents and in what location) to understand the context in which these SVAC events are taking place. The graph above shows that the incidence of SVAC rose to its highest point before the democratic transition in 2010. Over the same period, sexual violence tripled by 2007 to the highest recorded in Myanmar during the 18 years we collected counts of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), Myanmar’s conflict was at one of its deadliest points in 2007. But the dramatic shift was the increase in sexual violence, which precipitated by one year the peak in both SGBV counts and conflict deaths in 2007.

As the conflict intensity started to decline in 2008 and 2009, we see the counts of sexual violence incidence also begin to decline. In the first graph, we then see a rise in counts of sexual violence between 2011 and 2012, and again between 2015 and 2016. The rise in SVAC counts on both occasions occurs a year prior to the rise in conflict intensity.

Our dataset shows that in Myanmar the counts of sexual violence start to increase nearly a year before a spike in conflict. The increase in sexual crime (not reports) is a warning of the conflict escalating. Therefore, it is important to have counts of the numbers of women and men, girls and boys, being subjected to sexual violence in conflict-affected locations.

Building the PSVAP database has led us to further ask how we can use data and knowledge on patterns of reporting to intervene. With more information on the location of the crimes, the perpetrators, and the organisations reporting sexual violence in conflict, we can better report, respond to, and prevent situations of future violence.

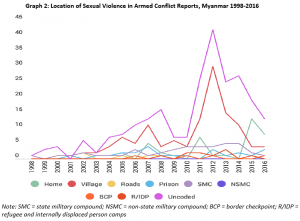

For instance, the graph below shows that the second highest reported location is camps for refugees and internationally displaced persons.

Sadly and unsurprisingly, of all the locations where sexual violence was reported, refugee and internally displaced camps are not safe spaces for Myanmar’s refugees. There is a need to dramatically improve cross-camp analysis of the risk of sexual violence in these locations.

Ideally, priority needs to be given to the improved IDP camp security to protect women and girls from sexual violence, including the creation of female security patrols within these camps. There should not be locations where soldiers can enter and there should be agreement between the Tatmadaw (Burmese military) and the Ethnic Armed Organizations on camps being ‘no-go’ zones.

This is crucial for thinking about early warning and prevention but also indicates the difficulty: these camps have become the sites of conflict in Myanmar. With their location often between the state-controlled and non-government controlled areas, populations are living within no-man’s land. This makes it all the more important, yet challenging, to ensure that camp populations have access to health services, justice mechanisms and protection that is neutral and independent from the conflict itself.

To prevent and protect, we need to know where human rights defenders and humanitarian workers can be best located to assist survivors and report on the crimes. They put their lives at risk documenting such violence, so when those being targeted tell their story – at the risk of more violence, retribution, shame and stigma – there must be an effort to mount a response that protects and prevents.

These experiences should be part of the peace process discussions, specifically those on ceasefire implementation at the 21st Century Panglong Peace Conference. Addressing sexual violence is not a negotiable condition for achieving peace.

The potential to predict where and when sexual violence in conflict will take place is possible through an analysis of the reports in the PSVAP dataset. The dataset also raises the question: if we can predict sexual violence in conflicts by looking at patterns and counts of reported violence, then don’t we also have the moral responsibility to prevent that violence in the first place?

Associate Professor Sara Davies is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Associate Professor, Centre for Governance and Public Policy, School of Government and International Relations, Griffith University. In 2018, she was appointed editor of the Australian Journal of International Affairs along with Professor Ian Hall.

Jacqui True is professor of politics and international relations and an Australian Research Council Future Fellow at Monash University, Australia. She is Director of the Monash Centre for Gender, Peace and Security.

This article was first published in Policy Forum on 29 May 2018 and is reprinted with permission.