Reversing the Surveillance State’s Gaze: “Sousveillance,” Drones and the Global War on Terror

The disruptive act of “Sousveillance” — the French “sous” (below) to designate the inverse of “sur” (above) — has become central to the contest between authoritarianism and free speech: that is, the subversive act of looking Big Brother squarely in the eye.

In 2016, the British Transport Police rolled out their “See it. Say it. Sorted.” security campaign for the National Rail. The campaign took its cues from “If you see something, say something,” a slogan invented by a U.S. advertisement executive the day after 9/11, trademarked by the New York Metro Transit Authority in 2002, and eventually adopted by Homeland Security and other agencies as what the Washington Post called the new national motto. The British version added a novel warning for daily commuters, however: beware of photographers.

One of the ubiquitous posters featured a shadowy figure holding up a smartphone to take a picture of a CCTV camera near the ceiling. A woman, who appears on a CCTV monitor nearby, takes note of the suspicious activity. The relation of cameras to bodies sets up the morality tale. While the good citizen submits to the state’s gaze and vigilantly extends it, the suspect citizen refuses to submit and even turns the gaze back on the state. The addition of the hand-held camera as an object of suspicion was perhaps a natural elaboration in a country that possessed some of the densest CCTV infrastructure in the world, yet it was only a matter of time before this yen for criminalising photography made the trip back to the United States. In 2018, under the banner of “if you see something, say something,” the Department of Homeland Security began to warn of photography in public places as a “sign of potential terrorism-related activity.” The move prompted the American Civil Liberties Union and others to sound the alarm that such messages ran counter to constitutional right of expression and presented a significant chilling effect.

This newfound concern about the terrorism of photography betrays a latent tendency in public discourse regarding surveillance since 11 September 2001: the will to regulate practices of seeing.

This goes beyond prevailing in public debates of “security versus privacy” and the general legitimacy of new surveillance infrastructures. As the “See It, Say It” campaign indicates, a powerful dimension of the discourse seeks to discipline the public performance of the gaze by both naturalising the everyday performance of the official gaze and criminalising counter-visual performances. From CCTV cameras in subterranean London to the drone camera’s aerial occupation of Waziristan, the figure of the camera has become a focal point in this public negotiation of the security state’s power.

The camera’s mode of public performance — who wields it, where is it pointed — is a powerful symbolic condensation of this particular public drama. The CCTV camera at the train station not only gazes down at the platform, it also stands as an emblem of surveillance writ large, including the non-visual, invisible, and abstract world of “dataveillance.” Likewise, any given counter-performance of vision not only looks back, it also stands as an emblem of state transparency and free expression. Normalising the state’s claim to surveillance often entails policing of counter-performances of vision, particularly those that summon the potent figure of the camera to challenge the state’s monodirectional gaze.

Ultimately, we argue that these performative forces are locked in a struggle between authoritarian and democratic politics.

Theatres of Surveillance

Following 11 September 2001, images of a new threat — a shape-shifting spectre who skirts national borders and sublimates into digital networks — underwrote sweeping changes to the architecture of the Western security state. Promoted with a promise to safeguard democratic life, the new regime of counter-terrorism instead shifted state power in a decidedly less transparent and undemocratic direction by mimicking the essential qualities of the perceived threat: invisibility and secrecy.

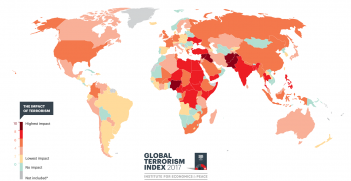

Such a shift has included a new reliance on black ops, black sites, extraordinary rendition, and absentee warfare using remote-controlled drones. Meanwhile, the security state massively stepped up its surveillance capacities. As the Edward Snowden revelations have shown, such capacities have far outpaced traditional surveillant practices such as the increased use of closed-circuit television cameras in public and commercial space. The National Security Agency, the Department of Homeland Security and the international surveillance alliance known as the “Five Eyes” — US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand — have gained the technical and political power to collect the entire haystack, to sweep up, archive, and data mine virtually every digital electronic transmission in what has been euphemised as “bulk collection.” The current reliance on the drone as weapon of choice, moreover, marks the centrality of surveillance as a theme, where entire geographies are subject to a new prototype occupation, one marked not by storm troopers kicking down doors on the ground but by persistent intensities of remotely operated vision in the sky.

Ample research empirically documents the chilling effect on freedom of speech and freedom of expression in the wake of the Snowden revelations in 2013 which exposed the level of surveillance undertaken by otherwise democratic governments. Numerous examples show that, on aggregate, demonstrate a significant chilling effect, one that has generated a climate in which both citizens and media are less willing to oversee and deliberate the actions of their own governments. Free speech and democratic debate have effectively been stifled by overly broad and exceptional counterterrorism laws that are purported by governments as necessary to prevent terrorism and to safeguard democratic life itself. The chilling effect has thereby reduced the capacity in democratic societies to question existing surveillance regimes, let alone whether these constitute too large an infringement on citizens’ rights and freedoms.

Sousveillance

In its simplest formulation, “sousveillance” can be described as the multitude of vernacular resistances that contest the normalisation of official surveillant operations. The history of this particular term extends back before its coinage to 1998 when MIT professor, engineer and video artist, Steve Mann, published something of a manifesto in the art journal, Leonardo, regarding ways that people might respond to the growing intrusion of surveillance cameras in everyday life.

For nearly two decades, Mann had been experimenting with a “WearCam” headset that recorded and transmitted video the user saw in an over-the-eye display. During this time, Mann became aware of a double standard. While CCTV cameras seemed to be everywhere, his own WearCam apparatus was treated with a certain amount of hostility and suspicion, especially by retail store managers. Mann responded by developing strategies for calling attention to this double standard and asserting a right to record.

Although Mann pays passing lip service to Foucault’s notion that power in the panoptic arrangement is imminent and diffuse, the goal of this quest seems to be finally rooting out Big Brother and looking him squarely in the eye.

Nowhere From Everywhere: Sousveilling the Drone

Although commonly called a weapon, the drone is first and foremost a way of seeing, of distributing the gaze of the state over vast territory, from the Mexican-American border to Peshawar Province. In such theatres, before the drone ever goes kinetic, it hangs in the sky often for days on end, filling servers with optical data and feeding the military bureaucracy known as the “kill chain.”

Outside the closed corridors of power, however, the drone has a second theatre of operations in public consciousness. This public face consists of viral drone strike footage, news stories, and filmic representations from The Bourne Legacy to Zero Dark Thirty. The mosaic of available drone imagery and its attendant discourse tells a consistent story about the technology, the enemy, and ourselves that justifies an unbounded War on Terror.

This “drone vision” does not just describe the narrow selection of objects the public sees through the drone camera. First and foremost, it describes a gaze, a habit of looking that structures relationship to the security state. The drone, as it has been normalised in public culture, cannot be separated from these practices of looking. In some ways, they render the machine hypervisible insofar as drone vision is always available and the drone always present. In other ways, the drone is absent and invisible to this public eye, rendered see-through by virtue of being seen through.

These habits of seeing become apparent when one challenges the structure of the gaze. Beginning in 2013, for example, anti-drone protesters began to get press for staging demonstrations in cities across the US as well as drone manufacturing sites like General Atomics in San Diego.

As we advance from the old system of targeted surveillance — where the suspect is first identified and then surveillance is acted upon the target — to the new system of “bulk collection” — where everyone’s data is collected first in order to then identify the target —, these threats have been magnified. Indeed, we can empirically demonstrate the significant “chilling effect” that the performative discourse of surveillance has had on free expression and the willingness to engage in democratic deliberation about controversial issues. The result has been a paradox: state surveillance has undermined the very democratic process that it was ostensibly designed to safeguard.

With traditional pathways for discussion, dissent, and free speech increasingly foreclosed, visual counter-performances that “look back” have become some of the very rare and therefore politically important sites of resistance in democratic societies. We theorised these counter-performances by extending Steve Mann’s notion of “sousveillance.” The struggle between surveillance and sousveillance, as we have conceptualised it here, goes beyond the practice of data gathering. Instead, it is a struggle to naturalise the prerogative of state surveillance on the one hand and, on the other, to disrupt and denaturalise this prerogative. In this way, the camera acts as a potent figure in an ongoing debate, rendered in a grammar of visual vectors, about the possibility of democratic participation. Theorising the push and pull of this performance has been the main objective of this article, but we also hoped to illustrate with sousveillant performances undertaken by a range of artists and activists.

Perhaps not surprisingly, these projects have gravitated to that ultimate emblem of the post-9/11 security state, the drone camera and its established “theatres of surveillance.” In one way or another, each project has rendered visible what has been kept from sight, visually contested the directionality of the surveillance camera, and generated important political spaces for alternative, resistant deliberations. It is perhaps also not surprising that these potent acts have triggered various attempts to police and criminalise the very act of looking back. From Apple’s rejection of Begley app to the New York Police Department’s arrest of Essam to the suggestion that photography is “sign of potential terrorist activity,” the surveillant state shows signs of pushing back.

Through the dust of these struggles over security state power in the War on Terror, one thing comes into stark focus: we have moved beyond the conventional “security versus privacy” dispute and now must entertain surveillance as a visual contest, with the figure of the camera at the centre, between free expression and authoritarianism.

Associate Professor Roger Stahl studies rhetoric, media, and culture at the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Georgia.

Dr Sebastian Kaempf is senior lecturer in Peace and Conflict Studies at the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland.

This article is an extract from Stahl and Kaempf’s article in Volume 73, Issue 3 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled “Sousveilling the Global War on Terror.” It is republished with permission.