Renegotiating the Indonesia-Australia Maritime Boundary Agreement?

This March, Timor Leste and Australia finally came to an agreement on a maritime boundary in the Timor Sea. How might the recent agreement affect the Indonesia-Australia relationship?

After a long process of negotiation, Timor Leste and Australia recently agreed on a permanent line dividing seabed (continental shelf) and water (exclusive economic zone, EEZ) between them in the Timor Sea. The maritime boundary agreement was signed on 6 March 2018.

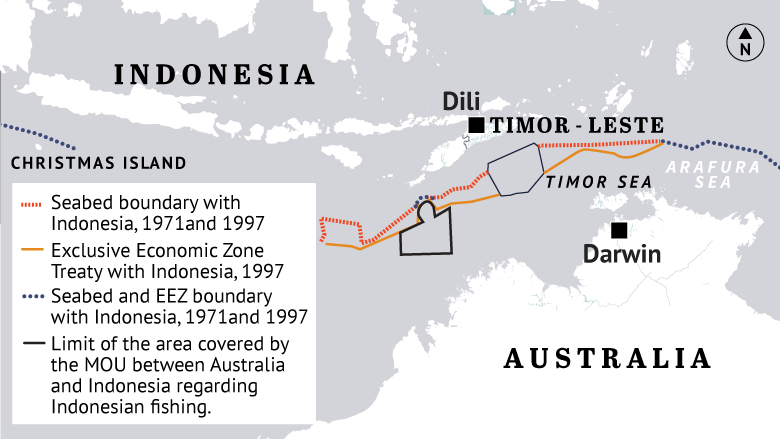

Both sides view that this historic agreement marks a new era of better relationships between the countries. In the area, this is the first permanent maritime boundary line ever drawn by two sovereign countries. The first attempt was done by Indonesia and Australia with an intention to involve Portuguese Timor. Unfortunately, Portuguese Timor refused to participate, so the lines were agreed between Indonesia and Australia. The 1972 agreement divides seabed only, not the water column, and leaves a gap that was coined the Timor Gap.

In 1997—when East Timor (formerly, Portuguese Timor) was part of Indonesia —an agreement was signed between Indonesia and Australia. Unlike the 1972 agreement, the 1997 one does not leave a gap and it divides water columns between the two countries. Interestingly, the location of the 1972 and 1997 are not coincident lines which means the division of water columns is different from the division of seabeds. Consequently, there is space in the Timor Sea where the seabed is for Australia while the water column above it falls within Indonesia’s jurisdiction.

Practically speaking, Indonesian fishermen are allowed to fish in the area but oil and gas extracted from the seabed are only for Australia. Interestingly, sedentary species like sea cucumber belongs to the seabed, hence, for Australia.

With the independence of Timor Leste in 2002, following the 1999 referendum, the 1997 agreement no longer reflects the geopolitics in the area. Timor Leste, independently, needed to settle its own boundary with Australia and it finally did on 6 March 2018.

It is not surprising that the line segments drawn in the Timor Leste-Australia agreement run closely with the 1997 Indonesia-Australia boundary lines. Some segments of the 2018 line even coincide with the 1997 ones. This confirms that certain segments of the 1997 line need to be revised, especially around area that is now dealt with by Australia and Timor Leste.

It is acceptable, therefore, that Indonesia proposed a revisit of the existing agreement between the Indonesia and Australia. It is a matter of logical consequence that the 1997 agreement needs to be revised, for it no longer, once again, reflects the geopolitical situation in the region. It is good to see how Australia responded to Indonesia’s proposal. In a meeting between Indonesia’s and Australia’s foreign ministers in Sydney on 15 March 2018, both sides shared a view that Indonesia and Australia need to revisit the 1997 agreement.

While revising the 1997 agreement is viewed as logic by many, many others might have different views. A renegotiation of a boundary agreement might not be seen as appropriate. This is understandable in relation to the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which states that boundary treaties are excluded from the rule that a party to a treaty may invoke “a fundamental change in circumstances” as a ground for terminating a treaty. In addition, the 1978 Vienna Convention on Succession of states in Respect of Treaties also provides that a change of states does not affect a boundary established by a treaty.

However, the 1997 agreement is yet to be ratified by the Indonesian side. Hence, the agreement is not a yet a full treaty so that its revisit is possible.

In my personal opinion, Indonesia and Australia will certainly need to be careful and gentle when they revisit the agreement. It has to be recognised that the revision of the 1997 agreement should be viewed as a logical consequence of the newly agreed boundary between Timor Leste and Australia. A revisit is required in order to make the agreement comply with the current law and reflect the current geopolitical setting in the region. Let us see how the two countries will deal with this issue.

I Made Andi Arsana is a lecturer and researcher at the Department of Geodetic Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. Andi was a member of the Indonesian Delegation at the 4th Indonesia-Australia Dialogue on 8-10 April 2018 organised by the Australian Institute of International Affairs with the support of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and PwC. This is his personal view.

This article is published under a Creative Commons licence and may be republished with attribution.