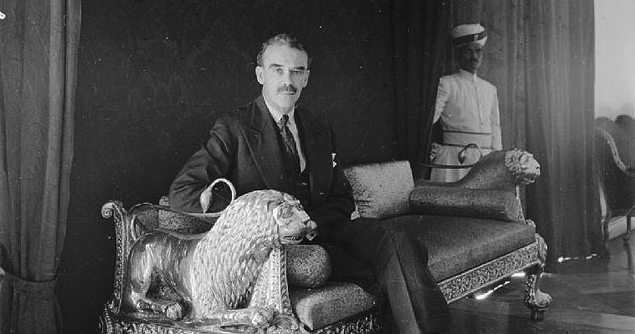

R.G.Casey: Minister for External Affairs 1951-60

In analysing foreign policy, the great forces of national power and politics can dominate explanations and expectations.

Personalities bob and weave through story. Yet you don’t have to subscribe to the ‘great man’ theory of history to think that individuals are a crucial ingredient in turning any tale. Anecdotes can have as much explanatory firepower as armies.

To bring anecdote and analysis together, the Australian Institute of International Affairs is publishing a series of books examining the role and influence of Australian foreign ministers. The first is on R.G.Casey, Minister for External Affairs from 1951-60. The second book, covering 1960 to 1972, will soon get its own review in the Reading Room.

On the evidence of the first two efforts, the AIIA has hit on a marvellous formula, mixing great yarns with high quality discussion of power and politics. In the meeting room at Government House in Yarralumla, gather a bunch of retired Australian diplomats for a day, ‘an excess of excellencies’, as one put it – to talk over ground set by some expert analysts. The meeting to discuss Casey ‘Fifty Years On’ took place in February, 2010.

The book is formed by a series of fine papers and the comments and memories they provoked. James Cotton writes on Casey’s understanding of Australia’s place in the world. This is classic Cotton, smart, sharp and illuminating. He uses the title of Casey’s book ‘Friends and Neighbours’ to illustrate the tensions and contrasts in Casey’s international mind map. On the friends side, Casey could write easily as an Australian Briton (‘we, the British’) and push hard over a long career to win every available Imperial honour.

Australia’s neighbours, though, presented a stark challenge to Casey as ‘the most unsettled region in the world.’ Casey’s engagement with Asia was energetic, but he reflected in his diary in 1952 – perhaps thinking of some of his Cabinet colleagues – ‘we, in Australia, are living in a fool’s paradise about the East.’

The Minister’s relations with his own department are discussed in two papers on Casey’s dealings with major figures of Australian diplomacy. Jeremy Hearder writes on Casey and James Plimsoll, noting how the curse/blessing of travel is ever upon the brow of Australia’s foreign minister. Casey was overseas for an average of three months a year, often for more than four weeks at a time. One of the yarns about Plimsoll is his notorious ‘bottom drawer’, a bureaucratic black hole where troublesome documents were quarantined for long periods of ‘masterly inactivity.’

Peter Edwards, author of a biography one of the great Canberra mandarins, Arthur Tange, writes about Casey’s fatherly approach to all of his diplomats as a substitute family: ‘Tange and his departmental colleagues admired and cared for Casey as a man largely because he so clearly admired and cared for them… He took a personal interest in the health and welfare of departmental officers, on occasion reaching into his own pocket to ensure, for example, that a necessary operation was undertaken.’ As Garry Woodard remarks, if External Affairs wanted to spend more than 50 pounds on anything in the 1950s, it had to be referred to Treasury.

Diane Langmore, author of a biography of Maie Casey, writes on the powerful husband-wife partnership, not least the view that Maie provided the push and much of the smarts. After a long talk with Casey, Harold Macmillan noted in his diary: ‘He is very pleasant – but not, I think, very clever. Mrs Casey is though.’ Robert Menzies saw Maie as the decisive ‘Lady Macbeth.’

The couple shared the intrigues of career, a love of travel and a passion for flying. They functioned like good allies, according to one of Casey’s private secretaries, Richard Gardner: ‘They respected each others’ territory and found that they could come into line on most major matters and agree to disagree on some minor ones. The only serious disagreements between the two would have been “who drives the Bentley” or “who has first use of the Cessna tomorrow”.’

The stories from the former Australian diplomats bring it to life. Start with Garry Woodard’s comment that Casey was a devoted member of the Melbourne establishment and ‘a Melbourne man.’ Woodard illustrates what this means by quoting the story of a diplomat’s wife, Elizabeth Searcy, telling her four daughters the story of Easter: ‘When she had finished one of the daughters said: “Mummy, Jesus was a very good man, wasn’t he?” When Elizabeth agreed, she asked: “Mummy, was he a Melbourne man?” R.G.Casey was indubitably a Melbourne man, though born in Queensland, and he was indubitably a good man.’ The phrase ‘good man’ was great praise from Casey, Gardner says, and ‘you felt as if you were a subaltern on the Western Front in 1915.’

The Minister may have been a good man but he was hopeless at winning in Cabinet. Part of this was the dominance of Menzies; equally it was Casey’s style. Edwards writes: ‘Casey’s ineffectiveness in Cabinet was all too well known. His inability to get increases in the foreign aid program, and his tendency to find himself in a minority of one or two on other issues, undermined his authority, as did his tendency to give rambling travelogues to his Cabinet colleagues.’

James Ingram thinks that Casey’s understanding of how diplomacy gets done reflected his own strengths and weaknesses: ‘Casey sees diplomacy as process, which of course it is. But even his ideas about process reflect his own style: his style of cultivating “top chaps” everywhere, of knowing all his top chaps.’

Alf Parsons views Casey as a follower not an innovator: ‘I think his capacity to listen and process was questionable. I remember once Jim McIntyre saying of Casey, “Yes, he’s a great player to work with; he’ll listen to anyone, particularly to the last one he spoke to”.’

Bill Pritchett has a gem of a yarn about his time as a young diplomat in Singapore, trying unsuccessfully to supply the shirts that Casey was ordering. And Pritchett thinks while the Minister may have had trouble convincing his Cabinet colleagues, Casey’s energy and message did reach out into Australia: ‘Casey was in the public eye by his own efforts and by his position as foreign minister for a very long time. He was speaking about Asia and I think that did something; I think that had some impact upon the Australian public’s perception, which was useful.’

This is a great start to what promises to be a wonderful series. R.G.Casey: Minister for External Affairs 1951-60, AIIA, 2012, is edited by Melissa Conley Tyler, John Robbins and Adrian March. You can order the Casey book ($15 plus postage) here

http://20.185.176.227/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Ministers-Series-Book-Order-Form.pdf

or download it for free here.

http://20.185.176.227/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/casey-book-final-revised.pdf

AIIA, R.G.Casey: Minister for External Affairs 1951-60, 2012, edited by Melissa Conley Tyler, John Robbins and Adrian March.

Reviewed by Graeme Dobell, Journalist Fellow, Australian Strategic Policy Institute.