Iran's Hijab Protests

Tehran’s ‘Girl on Enghelab Street’, silently waving her hijab above her unveiled head, has prompted a new round of protest against Iran’s modesty laws. Is there the momentum for change?

The end of 2017 and the start of 2018 saw a wave of anti-government protests in major cities and towns throughout Iran. Together, they became the largest protest in the country since the Green Movement during the disputed 2009 presidential elections.

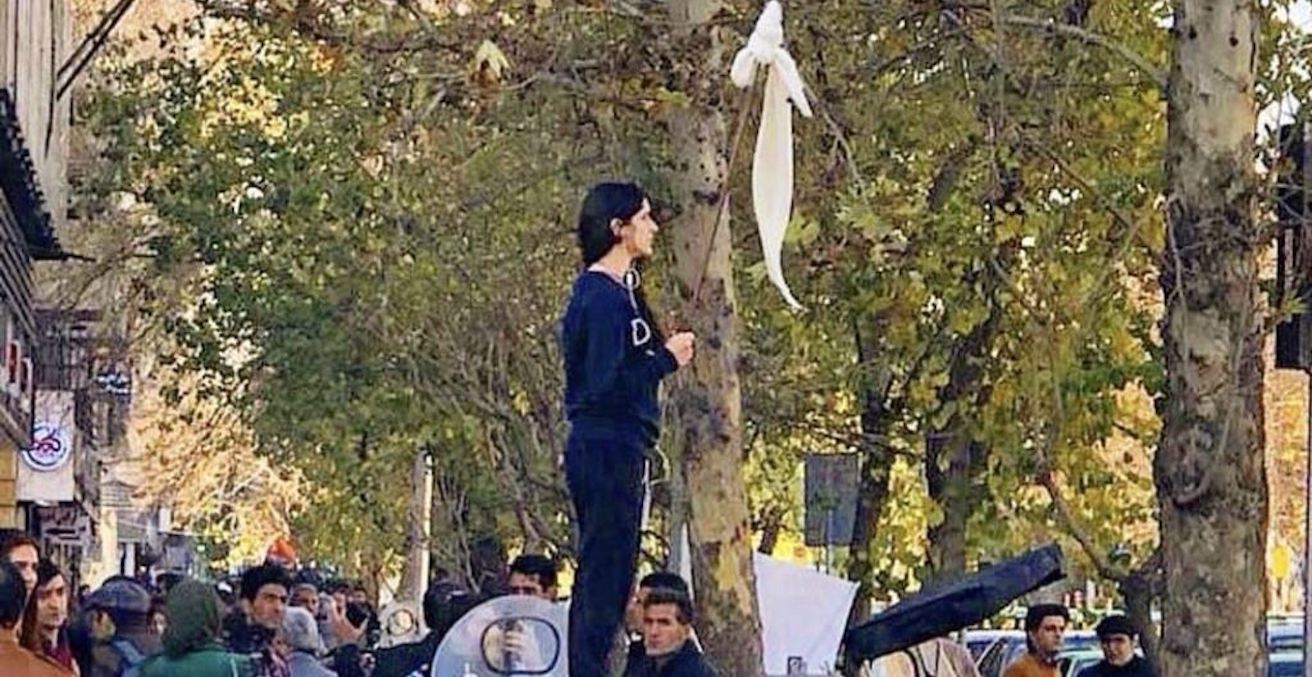

During that time, on 27 December 2017 an image of a young woman called Vida Movahed standing on a telecoms box in Tehran spread on social media. The importance of the image of the woman, later dubbed the ‘Girl on Enghelab Street’, was that she was unveiled and was waving her headscarf on a stick in the middle of the protesters, displaying her uncovered hair against the modesty laws of Iran. The simple gesture has reignited the debate in Iran over the compulsory hijab for women.

The hijab before 1979

In the decades before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the hijab was optional for Iranian women. Indeed, under the Shah, being veiled was often seen as a form of backwardness. As anti-Shah sentiment began to grow in the lead up to the revolution, many female students and middle-class women began to wear the hijab as a form of protest against the Shah and as a nationalist symbol against Western consumerism.

Following the revolution, the compulsory hijab was slowly introduced. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini decreed that women should wear Islamic attire if they wished to leave the house, resulting in 100,000 women taking to the streets in March 1979 to denounce such a measure. The protests would be to no avail.

The hijab was first made compulsory for women working in government and public office. In 1983, it was made compulsory for all women regardless of religion or nationality. During the early years Islamic attire was strictly enforced and the slightest glimpse of hair was met with harsh punishment by law enforcement.

For the new Iranian government, enforcing Islamic modesty on women was a tool for implementing strict Islamic ideology on its citizens. However, over time this changed. Today, many Iranian women flaunt their hair through fashionable headscarves and often push the boundaries of the government’s modesty laws.

My Stealthy Freedom

In 2014, exiled Iranian journalist Masih Alinejad established an online movement called ‘My Stealthy Freedom’. Starting on Facebook, this online movement shares photos of Iranian women, young and old, without headscarves in various locations around Iran.

Over the past few years, this movement has garnered over a million followers, praise from international human rights organisations and criticism from Iran’s clerical rulers. While promoting anti-compulsory hijab, Alinejad has also condemned foreign female dignitaries who have worn the headscarf on official visits to Iran. She has lambasted the former and current EU High Representatives of the Union of Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton and Federica Mogherini, for covering their hair during nuclear negotiations in Iran and has also criticised Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop, for wearing a loose black headscarf on her official visit to Iran in 2015.

My Stealthy Freedom has once again come to global media attention due to its coverage of the girl on Enghelab Street, who was inspired by Alinejad’s White Wednesday campaign, which calls for women in Iran to wear white headscarves on Wednesdays as a symbol against the compulsory hijab.

Movahed was arrested on the same day as her act of defiance, igniting a social media campaign with the hashtag #where_is_she? Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, who herself has been jailed for investigating abuses by the government, also sought to determine the fate of the girl on Enghelab Street, and was the first to discover her whereabouts and identity.

Soon, there were a number of identical instances of unveiled women standing on raised platforms in the streets of major cities holding headscarves on sticks. Additionally, a number of men and conservative veiled women have spoken out in support of the campaign against the compulsory hijab.

The authorities have been quick to respond to the defiance against Iran’s modesty laws and had arrested 29 women for not wearing headscarves at the time of writing. Deputy Speaker of Parliament, Ali Motahari, tried to downplay the anti-hijab protests by incorrectly claiming that women were free to wear whatever they chose; while Iranian judge and prosecutor, Gholam-Hossein Mohseni-Eje’i, said the unveiled female protesters were on drugs or were agents of foreign influence.

As news of the arrests and defiance against the compulsory hijab began to circulate, a number of international media and human rights organisations as well as foreign governments began to speak out. Heather Nauert, spokeswoman for the US Department of State condemned the arrests of anti-hijab protesters. Amnesty International called for the release of all detained women who had been arrested for defying Iran’s modesty laws. CNN, Al Jazeera and the BBC are among many international news outlets to report on the ongoing anti-hijab protests.

Unveiling as protest

While these anti-hijab acts of defiance may seem trivial, according to reformist lawmaker Soheila Jelodarzadeh, it’s part of a much broader protest against the government’s harsh policies towards women, stating that, “Once upon a time we imposed restriction on women and put them under unnecessary pressure and that provoked these protests with women taking off their headscarves in the streets.”

For the Iranian government, enforcing strict modesty laws on women is becoming increasingly hard as civil disobedience festers. Under Ahmadinejad’s presidency, morality police patrolled the streets, strictly enforcing modesty laws. However, this failed to stop young, progressive Iranian women from flouting such laws.

The reformist government of President Rouhani has eased the enforcement of Islamic attire for women, providing greater movement for women to protest compulsory hijab. The Centre for Strategic Studies, a think tank associated with the Iranian presidential office, released a study in February indicating decreasing public support for compulsory hijab and greater support for relaxing overall modesty laws for women. The study concluded, “In a society where at least 40 to 50 per cent believe hijab is a personal and optional matter, it is very difficult to demand enforcement.”

For many women in Iran, the removal of these modesty laws and the compulsory hijab is a small but vital step into progressing women’s rights. It is a step towards narrowing the gender gap in Iranian society, including in the workplace and in family life.

With growing public support for abolishing the compulsory hijab, the clerical authorities in Iran will face increasing anti-hijab protests and further defiance of Iran’s Islamic modesty laws. However, the clerical rule will not accept such progressive movements easily. Law enforcement will continue to clash with anti-hijab protesters in the near future as the regime cracks down on general civil disobedience.

Nevertheless, this is another way in which the clerical rulers bury their heads in the sand and ignore continuing anti-government sentiment. In a society where increasingly more women are attending university and becoming more educated, to deny them the same rights as men, even in the simple realm of clothing, is risking further alienating Iranian society, especially women, from the theocratic government and its ideologies.

You can follow Masih Alinejad and My Stealthy Freedom on Instagram at @masih.alinejad and on Facebook at My Stealthy Freedom

Will McEniry is a former intern with AIIA Victoria and AIIA National Office. He visited Iran in 2017 as part of AIIA VIC’s study tour.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.