Preempting Incel-Inspired Violent Extremism in Asia

The attacks inspired by the incel movement could be considered the first form of violent extremism to originate online. While deeply rooted in the North American context, incel discourse could find itself a welcome audience in Asia.

The term “incel,” short for “involuntary celibate,” was popularised by the woman who started Alana’s Involuntary Celibacy Project, a “forum for men and women to talk about being lonely, where they could wonder aloud about why they couldn’t meet anyone.” The community, which was mostly built and sustained by online interactions, underwent a schism in the mid-2000s and broke off into two forums: the inclusive Incel Support and the misogynistic Love Shy.

Incels from the latter part of the spectrum would subsequently comprise the broader anti-feminist “manosphere,” which is characterised with extreme misogyny and proclivity for personal attacks. Incels divide the world into several tiers: there are the sexually attractive men (“Chads”) and women (“Stacys”); average people (“normies”); and incels. This worldview is built upon flawed, pseudoscientific premises associated with increased likelihood of support for or engagement in violence.

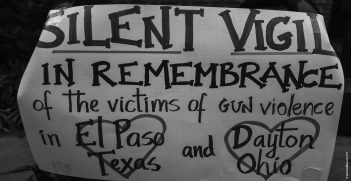

Incel discourse became linked to violent extremism in 2014, when 22 year-old Elliot Rodger killed six people in Isla Vista, California. In his final moments, Rodger posted online a video manifesto meant to justify his actions. Describing himself as a “supreme gentleman,” Rodger railed against his virginity, blaming women (“Stacys”) for choosing either mixed-race men, who he deemed inferior, or the superior “Chads.” Violent attacks attributed to the incel movement have caught the attention of security services in North America, with nearly 50 fatalities in the United States and Canada. The US Department of Homeland Security have since funded research on the incel movement.

In 2018, Canada set global precedent by indicting self-proclaimed incel Alek Minassian under existing terrorism legislation. Minassian killed ten people in Toronto, Canada in a vehicle attack. Prior to the incident, Minassian tweeted an explicit reference to Rodger saying, “The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!” Researchers consider incel as a “violent extremist ideology” that occupies a point on a spectrum of groups exhibiting militant misogyny, which includes groups such as neo-Nazis and the so-called Islamic State.

The incel movement’s traction in Asia

While incel-related violence appears rooted among white, male online subcultures found in industrialised countries in the West, it may find resonance in Asia. In some diaspora communities in North America, Asian men who deem themselves sexually disadvantaged have already latched onto incel identity. So-called ethnicels attribute their incel status to their ethnicity. South Asians dub themselves as “currycels,” while Southeast Asians identify as “ricecels.”

Anglophone online forums associated with incels such as Reddit or 4chan, which serve as vectors for incel discourse, have both reach and popularity in Asia. The transmission and possible reappropriation of memes emerging from the West into Asian political contexts have occurred. Pepe the Frog became the face of the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement. In the US, the smug cartoon frog has been classified as a hate symbol.

Misogyny manifests across both industrialised and developing societies. A 2019 United Nations study of three Asian countries (Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines) uncovered how misogyny, particularly violence against women, is predictive of support for violent extremist groups. The same study concludes that attacks on women’s rights and rights defenders are early warning signs for extremist violence. Across Asia, the worsening gender imbalance could lead to a range of problems, including more violence. An Asian incel movement could find a receptive audience, not only among the youth, but among older age groups raised under more patriarchal norms. It remains unclear whether the incel movement’s expansion into Asia would lead to activism or violent extremism. The socioeconomic milieu that nurtures incel discourse can be found in developed East Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea.

Preempting incel violence

Arguments have been made that pre-empting incel-motivated violence would require “securitising Incel.” Given the ongoing debate as to whether incel can be considered a cohesive political ideology, caution is advisable. The aforementioned Minassian indictment has been criticised as potentially the “world’s first incel show trial.” The incel online community, like any other Internet subculture, revels in shitposting “inane and contextless content.” Attempts to determine what are credible threats of violence versus satire have been recognised as a law enforcement challenge in the North American context. On the other hand, Asian countries beset by larger, deadlier violent extremist organisations may find the threat posed by incels a negligible risk.

Even for countries with established legal frameworks and security services to tackle various forms of hate speech and violent extremism, detecting incel-motivated violence before it occurs may not be feasible. The extreme misogyny expressed by violent incels should be viewed instead as a manifestation of deeper societal tensions, a variation of prevailing ”us-versus-them” discourse in both East and Western society. In countries where incel discourse has yet to result in physical attacks, statistics on online harassment can be considered as proxy measures to assess misogyny indirectly.

It may be more productive to tackle the broader issue of misogyny, whether it manifests as physical harm or mental distress. This include ensuring support for victims of violence against women and harsher penalties for online harassment. One example is revisions made to Singapore’s Protection from Harassment Act, which criminalises doxxing. Similar measures in other jurisdictions could build upon existing statutes and policies, reducing the need for extraordinary (and potentially politically controversial) steps such as labeling incels as terrorists.

Beyond governments, tech companies can take steps to deny the incel movement its online presence. To a certain extent, de-platforming incels has seen mixed success. Another approach is diversion, providing individuals on the path to incel-motivated violence with off ramps. This is similar to how individuals intent on seeking self-harm methods online are instead shown targeted ads leading to befriender or suicide prevention hotlines. Successful measures to preempt incel violence premised on fostering tolerance could result in across-the-board improvements and potentially prevent violent extremism emanating from other ideologies and movements.

Joseph Franco is a Research Fellow with the Centre of Excellence for National Security (CENS), a constituent unit of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He examines terrorist networks in Asia and documents global best practices in countering violent extremism. He regularly conducts field research in conflict-affected areas in Mindanao.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.