Slavery’s Ongoing Presence

Government and business representatives from 45 countries met in Perth this week to try and address slavery and human trafficking. It draws attention to a problem hidden on our supermarket shelves.

For many consumers in developed nations, slavery has been consigned to the annals of history; it seems a dusty relic that occupies the same semantic space as papyrus scrolls, aqueducts and imperial edicts. Unfortunately, this view is misguided.

The economic and social progress that allows people in the developed world to distance themselves from slavery has the potential to perpetuate its ills far into the future. Unless cooperative measures are adopted, the vast global economy that so many benefit from could continue to harbour modern slaves unable to refuse the contemptible circumstances thrust upon them.

Conceptualising the problem

Modern communication and technological progress has allowed businesses to source materials and labour from anywhere in the world, giving them both direct (contracted) and indirect (subcontracted) access to cheap, often unregulated, suppliers.

Access to such manufacturing processes has led to the affordable and readily available products consumers rely on today. This constant supply of cheap consumer goods is underwritten by a tangle of dense, multilayered, byzantine supply chains strewn across some of the world’s poorest populations.

While, prima facie, international companies strike legal, conscionable deals with overseas suppliers, those suppliers sit atop supply chains with dozens of layers and even more collateral elements. Somewhere in that quagmire, proper regulation and accountability are lost. Hidden within the deepest reaches of the manufacturing labyrinth are human beings forced to work under threat of psychological abuse, physical punishment and even death.

The most recent Global Slavery Index estimates that there are 45.8 million people enslaved today, many of whom are involved in the production process for goods that end up in countries like Australia.

While completely avoiding unnavigable supply chains may seem like the quickest and easiest solution, the truth is that companies and consumers are unlikely to wean themselves off overseas goods. Instead, government and civil society should work with businesses to modernise the process by improving regulation, increasing transparency and creating legislation that guarantees fair pay and eradicates bonded labour.

Models of cooperation

In the past, anti-slavery charities and other non-government organisations (NGO) would pounce at the opportunity to publicly ‘name and shame’ businesses for their association with felonious suppliers. This strategy results in lower rates of voluntary reporting and decreases the likelihood that businesses will uncover and eliminate slavery in their supply chains. Rather than adopting the combative approach of old, it makes sense to look to submissions to the recent Inquiry into establishing a Modern Slavery Act in Australia as an opportunity to reform Australian businesses’ relationships with their supply chains.

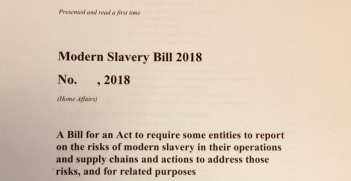

The inquiry gave special consideration to extant legislation in the United Kingdom’s (UK) Modern Slavery Act 2015 (MSA) and many of the submissions came from NGOs and companies with firsthand experience of its mechanics.

Transparency, routine reporting, and pre-competitive cooperation are the keystones of the MSA. It compels large companies operating in the UK—those with an annual turnover greater than £36 million (AUD$58.3 million)—to make their efforts to eliminate slavery from their supply chains public. The independent Office of Anti-Slavery Commissioner was also established, giving it the power to collaborate with law enforcement and border officers and promote best practice in supply chain transparency.

But an Australian iteration should go further; it should tackle the weaknesses of its British predecessor.

The British legislation’s lack of a central registry of modern slavery statements means that interested parties, particularly consumers, are unable to access the reporting history of the companies from which they purchase goods and services. A study by GT Nexus found that 52 per cent of American consumers would pay more for ‘ethically and sustainably’ sourced goods from overseas. Consumers should be able to use this information to vote with their purses, rewarding compliant and responsible businesses while avoiding those that choose merely to pay lip service to the initiative.

The UK MSA features no provisions that specify mandatory reporting content. So far, this has resulted in a wide range of reporting outcomes, from the diligent and detailed to the curt and cursory. Many Australian companies used the inquiry to call for regulation to standardise this process. Rio Tinto’s submission states that the company believes “the recommended reporting areas in section 54(5) of the MSA…should be mandatory” as they “support more effective comparison by a range of stakeholders”.

Similarly, Konica Minolta—a multimillion-dollar Japanese company operating in Australia—recommended that Australian legislators consider “mandated content” that includes “a description of organisational structure, risks, company policies and due diligence”.

These amendments, among others, would lead to an Australian Modern Slavery Act that provides a more reliable font of robust information; one that consumers, NGOs and even competing businesses can use to guide their behaviour in relation to modern slavery.

Perth forum

This week, Australia gets another opportunity to push for modern slavery legislation both domestically and regionally when the Bali Process Government and Business Forum brings business leaders, ministers and ambassadors from more than 45 nations to Perth. This renewed initiative, for the first time in its history, brings the private sector into the fold.

Civil society should be prepared to share resources and methodology with companies to help them accurately identify and quickly eliminate modern slavery in their supply chains. If businesses are expected to search for slavery in their supply chains, they will almost invariably find it; uncovering slavery is an indispensable step in helping those trapped in unfair conditions.

An Australian Modern Slavery Act with crucial additions would prompt companies to take the first step in saving millions from shrouded exploitation and could secure Australia’s position as a regional leader on the matter.