Payne Silent on Human Rights Following Visit to Myanmar

In stark contrast to much of the international community, Australia has failed to unreservedly condemn human rights violations following Payne’s visit to Myanmar.

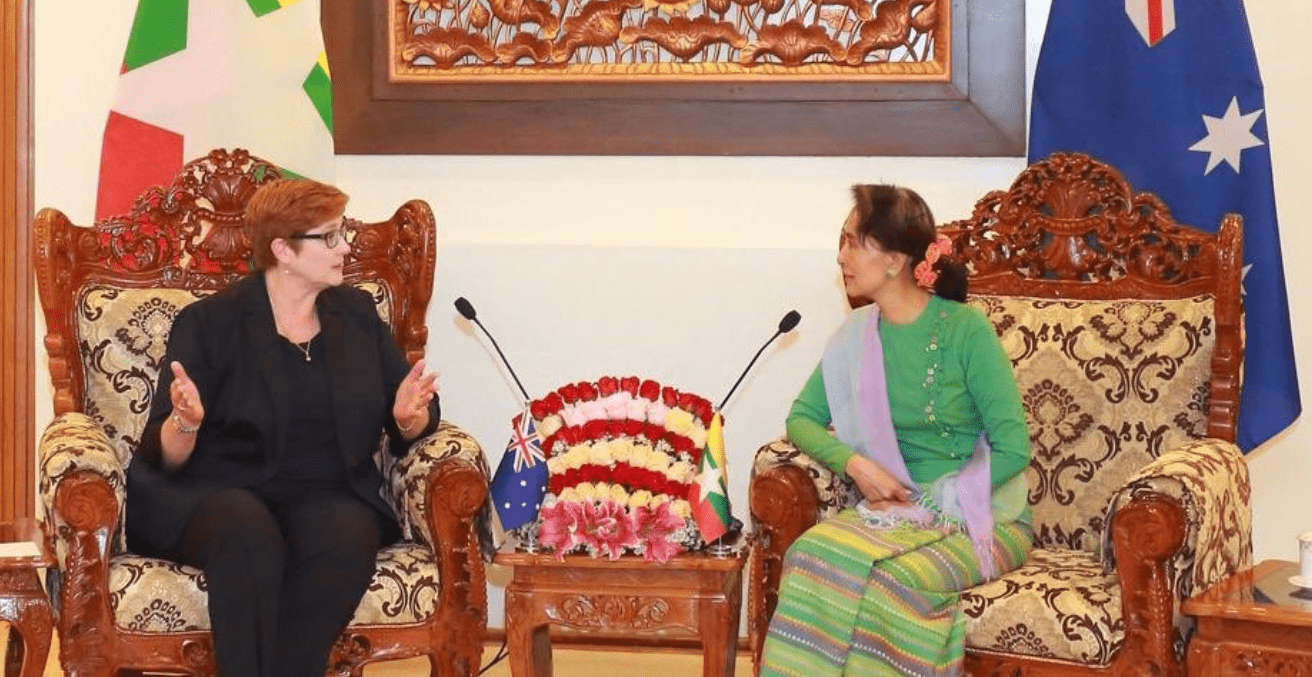

Last week, Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne visited Myanmar to “see at first hand the devastating humanitarian impact of the situation in Rakhine State.”

The visit came just over a year after a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign in Rakhine State, perpetrated by the Myanmar military, caused more than 600,000 Rohingya people to flee across the border into Bangladesh in just three months. As described in the report of the International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, the military killed thousands of civilians, committed sexual violence including mass rapes, burned hundreds of villages and “established a climate of impunity for its soldiers.” The report recommended that senior members of the Myanmar military be tried for genocide and called upon the UN Security Council to refer the situation to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

On return from Myanmar, Payne said she’d held meetings with senior government representatives, including State Councillor Aung San Suu Kyi, and that she’d “discussed Myanmar’s ongoing efforts to address the crisis.” She said she’d emphasised the importance of a “long-term, durable solution”, and that Australia would work with Myanmar to “encourage efforts towards peace and reconciliation.”

She didn’t say anything about the atrocities that gave rise to the humanitarian crisis that she’d visited Myanmar to see. She didn’t say anything about human rights violations, justice or accountability. She also didn’t say anything about discontinuing Australia’s support for the Myanmar military despite considerable public pressure to do so, and she certainly didn’t say anything about the ICC.

Let’s take a look at what other states have said.

In October, British Ambassador Karen Pierce told the UN Security Council that while the situation in Rakhine was “the most egregious example of the Burmese military’s conduct”, it wasn’t the only one, and that the military was also “conducting human rights violations across the country against other ethnic communities.” She stressed the importance of sending a signal to other countries “whose governments may be tempted to take a leaf out of the Burmese military’s horrific playbook and execute such crimes on their own people”, and said that all options should be considered including referral to the ICC or to an ad-hoc tribunal.

Sweden has highlighted the violations of international humanitarian and human rights law being perpetrated by the Myanmar military, and called for the UN Security Council to take meaningful action, including by considering a referral of the situation to the ICC.

The Netherlands has said “we need to refer the situation in Myanmar to the ICC and use all tools available to us to create meaningful change on the ground.”

France has called for the Security Council to “take up its responsibilities”, warning that “action or lack thereof is being looked at very carefully by those who might consider committing such crimes in the future.”

Australia has said things like this too, about other countries.

In 2013, Australia’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Gary Quinlan told the Security Council that where national authorities are unwilling or unable to investigate and prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law, “it is vital that the Council consider the referral of situations involving genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes to the ICC.” In 2014, referring to South Sudan, Quinlan said that “no party to the conflict should be under the illusion that there will be anything less than full accountability for … crimes against humanity and war crimes.” In October 2016, Permanent Representative Gillian Bird told the UN General Assembly that Australia was committed to “doing what we can to advance our common cause of ending impunity for those who commit the most serious international crimes that shock the conscience of humanity.”

Such statements reflect Australia’s foreign policy commitments to promoting accountability and the rule of law. Australia’s foreign policy commits to supporting international accountability mechanisms including the ICC, and its Humanitarian Strategy commits to promoting compliance with international humanitarian and human rights law. At the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016, Australia said we’d “systematically condemn serious violations of international humanitarian law and serious violations and abuses of international human rights law”, and “take concrete steps to ensure accountability of perpetrators when these acts amount to crimes under international law.”

Yet in this instance, instead of condemning the Myanmar military, Australia continues to support them, to the tune of around $400,000 a year. We’re one of the only countries that does so. The US, UK, Canada, EU, France and others have cut all ties with the Myanmar military.

Australia has justified its ongoing engagement on the basis that it’s “strictly limited to non-combat areas such as disaster relief and English-language training, and is designed to help promote positive change in Myanmar.”

This is simply not good enough. Would Australia have basis that engagement would influence its conduct? Would Australia have provided training to the Bosnian Serbs during the ethnic cleansing campaigns of the 1990s? No, and nor should Australia support the perpetrators of ethnic cleansing and possibly genocide in Myanmar. It cannot be justified.

Australia should follow the lead of the UK, France and others and cut ties with the Myanmar military. Australia should also act on its foreign policy commitments to condemn violations of international human rights and humanitarian law and take concrete steps to ensure that perpetrators are held to account, and should work within ASEAN to explore the possibility of a regional accountability mechanism as a possible alternative to the ICC.

Minister Payne assures us that Australia is working with Myanmar to “encourage efforts towards peace and reconciliation”, but this doesn’t send much of a message to future perpetrators of atrocities. In the words of Permanent Representative Gillian Bird, “history has demonstrated time and again just how difficult it is to prevent cycles of violence in the absence of justice. We must heed that lesson.”

Rebecca Barber is an Associate Lecturer in Humanitarian Studies at Deakin University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.