Obsession With Sykes-Picot Says More About What We Think of Arabs Than History

100 years ago today, the Sykes-Picot Agreement was signed, splitting the Middle East into the colonial powers’ rule. Does this secret accord hold any significance today?

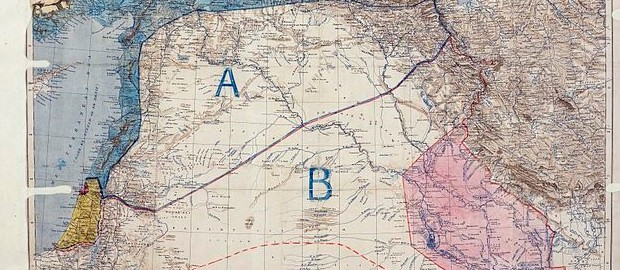

In 1915–16, Sir Mark Sykes, of the British War Office, and François Georges-Picot, French consul in Beirut, negotiated a secret agreement to divide the Asiatic provinces of the Ottoman Empire into zones of direct and indirect British and French control after the first world war.

The agreement also “internationalised” Jerusalem – a bone thrown to the Russian Empire, then a British and French ally. The Russians were worried that Orthodox Christians might be put at a disadvantage if the Catholic French had the final say about the future of the holy city.

Although Russia never officially signed the agreement, it acquiesced to it. In return, the allies pledged their commitment to Russian control over Istanbul and the Turkish Straits. They also agreed to direct Russian control over parts of eastern Anatolia (Asia Minor, or the modern-day Republic of Turkey) at the close of hostilities.

As straightforward as all this was, over the years the words Sykes-Picot have taken on two meanings – one significant, the other less so.

A dead letter

Let’s start with the less significant meaning, which alludes to the actual accord. Except for demarcating a line in the desert that anticipated the boundary between contemporary Syria and Iraq (drawn in 1922), the impact of the accord is zero.

It never went into effect. By the end of the first world war, it was already a dead letter. This was the case for a number of reasons.

In the first place, the British did not like the borders drawn between their zone and the French zone. In particular, the Sykes-Picot map placed northern Palestine and Mosul – two areas the British coveted – in the French zone.

Second, by the end of the war the British, not the French, occupied the inland Asiatic Arab territory that had belonged to the Ottoman Empire. Since they were playing a stronger hand than the French, they took it upon themselves to divide that territory into zones under the authority of the “Occupied Enemy Territory Administration”. And the boundaries of the various administrative zones conflicted with those established by the Sykes-Picot agreement.

In 1917, the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. Focused on consolidating power at home and not particularly concerned with access to holy places or inter-imperialist agreements, the new government renounced all secret agreements to which the tsarist government had been party.

Adding insult to injury, Russia published them, much to the embarrassment of former allies. Britain and France both viewed the changed circumstances as an opportunity to rethink their agreement.

Not really relevant

The irrelevance of the accord becomes apparent if one compares a map of the contemporary Middle East with the map proposed by the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Is any area of the region under direct British, French or Russian administration?

Is Jerusalem – and the adjoining region – under international control? Do France and Russia directly control parts of Anatolia? And does Britain directly control parts of Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula?

Whatever Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot agreed to, the current boundaries in the Levant (an area in the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing Syria, Palestine and Lebanon), Mesopotamia (the area around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq) and Anatolia actually resulted from two factors.

The first is the establishment of the mandates system by the precursor of the United Nations, the League of Nations. This system allotted Britain and France temporary control over territory in the region. The two powers took it upon themselves to combine or divide territories into proto-states in accordance with their imperial interests.

Britain created Iraq and Trans-Jordan after the war (Israel and Palestine would come later); France did the same for Lebanon and Syria.

Second, Anatolia remained undivided because Turkish nationalists fought a gruelling four-year war to drive foreigners out of the peninsula. The result was the contemporary Republic of Turkey.

Why, then, do commentators and others still focus on the Sykes-Picot Agreement 100 years after the fact? It wasn’t, after all, the first secret agreement that aspired to divide the Ottoman Empire among the allies; that would be the Constantinople Agreement of 1915.

A metaphor

The answer lies in the second meaning of the accord: its usefulness as a metaphor. During the last century, the expression Sykes-Picot has served three functions.

From the 1930s through the 1960s, Arab nationalists invoked the secret agreement as a symbol of Western treachery. The West, they claimed, thwarted the natural inclination of Arabs to unite in a single state. In addition, it supported the State of Israel — a “dagger stuck in the heart of the Arab world”, as then Egyptian president Gamal ‘Abd al-Nasser once put it – to achieve that goal.

From the 1980s to the present, Islamists, particularly those affiliated with al-Qaeda and now Islamic State (IS), have included references to the “Sykes-Picot boundaries” in their propaganda to connote a conspiracy the West (or, in the case of al-Qaeda, “Crusader-Zionists”) entered into to keep the Islamic world weak and divided.

Read about how Islamic State uses Sykes-Picot in its propaganda

For al-Qaeda, this conspiracy justifies its defensive jihad. For IS, it justifies an offensive jihad to re-establish a caliphate that, they anticipate, will eventually unite the entirety of the Islamic world.

Commentators in the West and elsewhere use the agreement to explain the contemporary turmoil in the Arab world. For them, it represents “blowback” — unintended and adverse effects of imperialist meddling in the region.

The American arming of the mujahideen in Afghanistan during the 1980s led directly to the rise of al-Qaeda and 9/11, for instance, and indirectly to the rise of IS. The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq unleashed a sectarian nightmare.

In a similar vein, commentators assert, imperialist meddling and the creation of “artificial” borders in the region at the end of the first world war prevented populations from consolidating nation-states based on their “natural” and “primordial” sectarian and ethnic identities (as, the argument would have it, had happened in the West).

All borders, not just those in the Middle East, are, of course, artificial. And if you choose to worry about the durability of states whose borders were drawn by far-off diplomats, worry not just about Syria and Iraq but about Belgium as well.

Most important, the fact that we tend to harp on “natural” and “primordial” ties of sect and ethnicity in this particular region feeds into the all-too-common tendency to view Arabs as primitives incapable of forming modern political identities. They most certainly are not.

For all the talk of artificial borders in this particular corner of the Arab world, it is easy to forget one essential fact: except for the decolonisation of the Gulf in 1971, and the unification of the two Yemens in 1990, the state system in the Arab world has been remarkably stable for almost three-quarters of a century. It has been more stable, in fact, than the European state system.

James L Gelvin is Professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of California, Los Angeles. He received his B.A. from Columbia University, his Master’s in International Affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University, and his PhD from Harvard University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation on 13 May. It is republished with permission.