Nuclear Security after NSS2016: Still Bridging the Gaps?

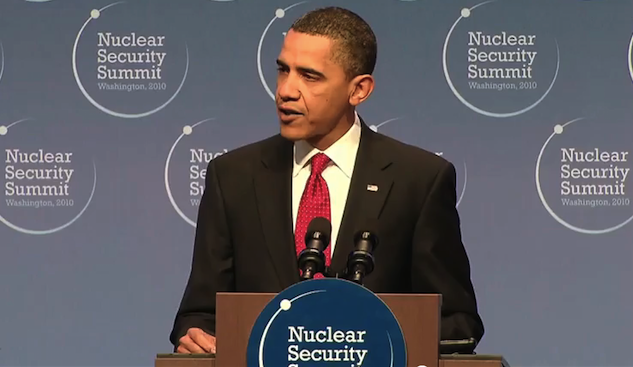

In his famous 2009 Prague Address, President Obama announced “a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years.” The result was a series of biennial Nuclear Security Summits that have brought world leaders together to cooperate on securing nuclear material from terrorism since 2010.

More than four years later and with the fourth and final Nuclear Security Summit having wrapped up in Washington DC this month, it is timely to review the extent of the progress made toward his aim and what challenges remain.

The summits have been incredibly successful at focusing attention and generating action to counter the threat posed by nuclear terrorism. This has been particularly evident in the voluntary commitments of ‘house gifts’, ‘gift baskets’ and Joint Statements that have been pledged at the summits and largely delivered upon. As a result of the more than 260 commitments made, there have been: upgrades at 32 buildings that house weapons-usable fissile materials; detectors installed at more than 320 international borders, airports and seaports; and the shutdown or conversion to Low Enriched Uranium (LEU) fuel of 24 research reactors and isotope production facilities. There have been new training centres and Centres of Excellence established, as well as joint commitments made on a number of issues including minimising Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU), cooperation on nuclear forensics, countering nuclear smuggling, cyber security, R&D and codes of practice.

A significant outcome of the summits, and the 2016 Summit in particular, has been the successful push to gain the last of the 102 ratifications required to see the 2005 Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM-A) enter into force. The original Convention was aimed at ensuring adequate physical protection of civilian nuclear material during international transport but was viewed as ‘incomplete’ due to its limited applicability. The 2005 Amendment strengthens the Convention by extending it to the physical protection of nuclear material in domestic ‘use, storage or transport’ and to cover the protection of nuclear material and nuclear facilities from sabotage. While it has taken more than 10 years to be achieved, the UN International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has now received the 102nd instrument and this legally binding commitment will finally enter into force on 8 May 2016.

The reduction in civilian stockpiles of weapons-usable HEU has been another notable success story from the summits, with more than 3.8t of HEU secured or removed from over 50 facilities in 30 countries. This has seen Taiwan and 14 countries declared free of HEU, including Ukraine and Libya just prior to recent conflict, entire regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean and large sections of Central Europe.

These are all fantastic outcomes but the rather harsh reality is that they don’t represent the full picture of all potentially vulnerable nuclear or radioactive materials. The success story with HEU reductions and commitment to eliminating stockpiles hasn’t occurred to the same extent with civilian stockpiles of separated plutonium; radioactive source security is still failing to garner the attention we see occurring with nuclear material. The Nuclear Threat Initiative’s 2015 report Bridging the Nuclear Materials Gap also highlighted that 83 per cent of the world’s roughly 2000-ton inventory of nuclear weapons-usable materials is categorised as “military” and sits outside the scope of international oversight mechanisms and standards. This doesn’t detract from the significant achievements achieved via the summits but a quick glance at the IAEA’s Incident and Trafficking Database suggests there’s still significant work to be done and that the progress achieved via the summits has been focused on a fraction of the material actually available.

The challenge of “bridging the gaps” isn’t restricted to categorisations, illustrated through two noticeably absent potential participants from the final summit: Russia and Iran (the former electing not to attend and the other not being invited). The summits overcame the exclusiveness of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty through the participation of India, Pakistan and Israel but the 53 countries invited to the summits equate to less than one-third of the UN IAEA member states being invited to participate. Given the global nature of the threat posed by nuclear terrorism, the concern is that limiting who is at the table arguably promotes a continuation of the patchwork quilt of arrangements (and gaps) that leaves facilities and material at risk.

Which brings us to what is arguably the biggest post-summit challenge: maintaining the momentum. At the 2014 Summit President Obama suggested the final summit would be transitional, seeing the change from a leaders’ summit towards a sustainable model that leverages global infrastructure and is maintained through meetings of government ministers, experts and international institutions. The final Action Plans support this, promoting the continuation of the summits’ work through the UN, the IAEA, INTERPOL, the Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction and the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism. While action can and will occur via this infrastructure, the CPPNM-A and the reductions in HEU underscore the role of the presence of heads of state in creating a clear sense of priority and ensuring action prior to the next summit. One can’t help but wonder if the attention and action the summits harnessed so well will be able to be maintained without the high-level political interest and collective accountability generated through recurring leaders summits.

The summits didn’t secure “all vulnerable nuclear material around the world” but significant progress has clearly been made. With the growing spectre of terrorism across the world, it’s critical we do all we can to maintain the momentum for depriving terrorists of nuclear material and radioactive sources with which they can do harm.

Jasmin Craufurd-Hill is an Executive and Board member of Women-in-Nuclear (Global), a worldwide association with over 25,000 members working professionally in applications of nuclear science and technology. The views expressed here are her own and do not reflect an official position of WiN Global. You can continue this discussion with Jasmin on twitter: @jasminchill

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.