No Far-right Electoral “Earthquake” to Shake the European Union

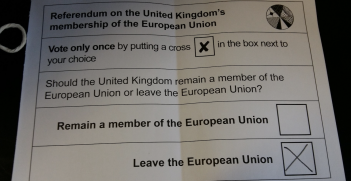

While some nationalist forces, including Nigel Farage’s brand-new Brexit Party, scored wins at a local level, overall there was little support for anti-EU parties in the recent European Parliament elections. Meanwhile, the future of Brexit remains as uncertain as ever.

Europe continues to fragment with some sharpening political divides, but the European Union remains intact as it starts the process to elect a new leadership team to take office on November 1. By coincidence, one day earlier Britain is scheduled to leave the EU. However, leaving remains as much in doubt as it was before Brexit ultras in the Conservative party forced Prime Minister Theresa May into a tearful resignation last week.

Detailed analysis of the results of the European Parliament’s elections on the weekend shows that the far right “earthquake” — that was predicted to shake the EU’s Berlaymont headquarters to its foundations — did not happen. Commission officials were able to emerge smiling on Monday morning.

But the stock markets told a different story. Investors hate uncertainty, and the erosion of support for the centre-right and centre-left parties that have governed Europe for decades is an obvious recipe for uncertainty. Boris Johnson’s cause may also be hampered by a long wait to stand trial on accusations of misconduct in public office, relating to lies he allegedly perpetrated throughout the 2016 referendum campaign.

The centre-right European People’s party and centre-left Socialists and Democrats lost their combined majority for the first time since the inception of the European Parliament, though they remain the two biggest parties.

Yet there was little support for anti-EU parties, except in England where the vexed Brexit issue dominated. Demands for speedier action on climate change brought a surge in support for the Greens right across the continent. The party’s number of MEPs rose by almost 40 percent, up to 69 percent, giving it a significant say on who runs both the EU and the European Central Bank. The Greens did particularly well in France, Britain and Germany. In the latter it came second only to Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, and top in key cities like Hamburg and the capital, Berlin.

Some British commentators made much of the fact that the French right-wing National Rally (NR) party led by Marie le Pen — who was soundly defeated by Emmanuel Macron for the French presidency two years ago — had inflicted a “humiliating defeat” on the president. The truth was that though NR narrowly won with 23.1 percent, just ahead of Macron’s Republique En Marche, it got fewer votes than in 2014, despite a 50 percent turnout. Macron, of course, now has a swathe of seats in the European Parliament, where previously he had none, and so will be able to wield more influence. The humiliated parties in France were the Republicans and the Socialists that, until Macron arrived, dominated French politics since the European Parliament was created.

In Germany, Europe’s powerhouse, it was the Socialists who were on the receiving end of voters’ discontent. Though Merkel’s Christian Democrats still top the country’s vote, nothing is certain or guaranteed as they will have to pay attention to the Greens, perhaps even considering a coalition if these trends persist in the 2021 general election.

Immigration — or rather wholesale opposition to it — seems to have subsided as a major issue across the EU, though it clearly influenced voters in some countries. Not surprising perhaps, in Italy the ruling populists grabbed 58 percent of the vote, relegating the two main centre parties to just 30 percent. The Five Star Movement fell further behind its right-wing junior coalition partner and could embolden the leader of the Northern League, Matteo Salvini, to head for a national poll later this year. Salvini, who campaigned on an anti-immigration platform, wants to form a coalition of like-minded MEPs, like Britain’s Nigel Farage, to force policy changes in the EU.

Poland may also join the anti-immigration lobby. The ruling conservative, anti-immigration Law and Justice Party topped the poll with 45.6 percent, well ahead of the pro-EU European Coalition at 38%. As expected, Hungary’s Viktor Orban saw his party take 52 percent of the vote as he railed against immigration. On the other hand, contrary to expectations, in the Netherlands this issue did not find much support. The centre-left Dutch Labor party actually won with 19 percent of the vote.

Britain, on the other hand, came out of the election as anything but a united kingdom. The country is split down the middle. Both ‘main’ parties, Conservative and Labour, are also split between those who want the country to leave the EU as soon as possible, and those who believe that would be a grave mistake, and were hammered in the poll. The ruling Tories finished fifth with only 8.7 percent of the vote, less than half that of their previous worst performance, and behind Labour that took an equally miserable 11.1 per cent of the vote.

The clear winner was Nigel Farage, former leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), who created the Brexit Party less than six months ago. Its single manifesto promise was to pull Britain out of the EU as soon as possible and by no later than October 31. He achieved 32 percent of the vote and 29 seats. While he won some of those seats by decimating the votes for the Tories and Labour, most of his party’s seats came from former UKIP supporters, which was wiped out in the election. While Brexit-supporting newspapers like the Sun, the Daily Telegraph, and the Express splashed headlines about Farage’s glorious victory for Brexiteers, the combined votes of those parties committed to remaining in the EU exceeded those voting for Brexit. Leading the “remainers” was the Liberal Democrat party, securing 20 percent of votes with their campaign slogan “Bollocks to Brexit”, as well as strong performances from the Greens and the Scottish Nationalists. The Brexit Party picked up votes in the traditional Labour heartlands of the North-East and Midlands, while the Liberal Democrats stole votes from the Conservatives. Lord Heseltine, a Tory grandee and former deputy prime minister in the Thatcher government, lost the party whip, which went to the Liberal Democrats. Alastair Campbell, a Labour stalwart and press secretary to former prime minister Tony Blair, was kicked out of the party.

In this milieu, Brexit seems as intractable as ever. Next week the Tories will start the process of selecting a new leader, with Mrs May’s successor almost certainly coming from the party’s ultra-right. At the last count, 12 MPs had put their names forward, and Conservatives will select two by a process of elimination over the next month. The 12 contenders will enter a ballot of 120,000 party members who, polls indicate, favour former Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson. This supposes that Johnson passes muster with Tory MPs, which is by no means certain since a “get Boris” campaign has sowed the seeds of doubt about his credibility for the top job.

Yet as the columnist Clare Foges, a former Cameron speechwriter, put it in The Times: “Many grassroots Tories complain the party isn’t right-wing any more, but infiltrated by a load of metropolitan wusses who probable drink pulped kale rather than real ale, and don’t know the words of the national anthem.” It is this group from the shires that will make the final selection for May’s replacement.

Whoever wins will have a tough job to deliver Brexit. Parliament is strongly opposed to a “no deal” Brexit, and Farage has no MPs in the Commons. Opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn is slowly coming round to the idea of a second referendum.

As 31 October approaches, whoever leads the Conservatives could find themselves in the same hapless position as Theresa May.

Colin Chapman is a writer, broadcaster and public speaker, who specialises in geopolitics, international economics, and global media issues. He is a former president of AIIA NSW and was appointed a fellow of the AIIA in 2017.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.