Morrison’s Moment of Truth in the Pacific

Can Australia’s prime minister convince the leaders of Pacific Island countries that he is serious about regional engagement when they are sceptical of Australia’s record on climate change?

Stepping Up in the Pacific

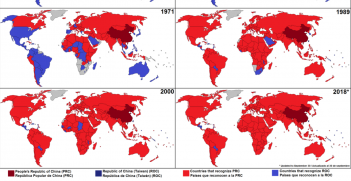

Canberra’s renewed interest in the Pacific islands is clearly driven by anxieties about the growing influence of an increasingly powerful China. It is in this context that Australia’s 2017 foreign policy white paper indicated Australia would “step up” and “engage with the Pacific with greater intensity and ambition.” Since coming to power in 2018, Scott Morrison has made the Pacific step up his signature foreign policy initiative. He has traveled to Fiji, Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, and told island leaders he considers Pacific island countries to be “family,” indicating a level of personal investment in the political relationship with island states previously unheard of from an Australian prime minister. In large part, he appears to have been warmly embraced by his island colleagues.

However, there is one area where tensions remain high. When he sat for dinner with the Fiji Prime Minister in January, Voreqe Bainimarama was pointed in his criticism of Morrison’s support for coal. He explained: “from where we are sitting, we cannot imagine how the interests of any single industry can be placed above the welfare of Pacific peoples [and] vulnerable people in the world over.” And this is the nub of the matter. Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter, and its domestic emissions are also climbing. While for their part, Pacific island states have championed global action to tackle climate change for decades. They point to scientific assessments from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which indicate that only decisive efforts to reduce emissions will avert catastrophic impacts: including more intense cyclones, dying coral reefs, ocean acidification, and coastal inundation. For low-lying atoll states, like Tuvalu, rising seas pose a threat to their very sovereignty and territorial integrity. At last year’s Pacific Islands Forum, leaders issued a regional security declaration which affirmed climate change as the “single greatest threat” facing the region. The theme for this year’s Forum is “securing our future.”

Rising Emissions, Declining Influence?

When it comes to climate change, Morrison is stuck between a black rock and the rising sea. He needs to convince island leaders he is serious about tackling the issue they see as their greatest security threat. However, he has no credible policy framework to reduce emissions. When Australia’s last prime minister Malcolm Turnbull tried to implement a national policy to address the most polluting sector – his ill-fated National Energy Guarantee – he provoked enough opposition from within his own ruling Coalition to be turfed from his job. Now, in order to square the emissions circle, Morrison is relying on a loophole in global climate rules to claim Australia is ‘meeting’ its commitments under the Paris Agreement, even while emissions continue to rise.

Here a little detail is needed. When the precursor to the Paris Agreement – the Kyoto Protocol – was negotiated in 1997, Australian officials secured a concession allowing emissions to rise, even while the rest of the industrialised world cut theirs. In what came to be known as the “Australia clause,” this allowed Australia to count emissions saved through modest changes to land-clearing laws. Having set only very weak targets in the first place, Australia was then able to “over-achieve” its commitments. Today, Australia intends to use surplus units from the Kyoto Protocol period as carryover credits to “meet” future commitments under the Paris Agreement as well. Doing so would allow Australia to avoid nearly half of its actual obligations to reduce emissions before 2030.

The Paris Agreement is a completely separate legal instrument to the Kyoto Protocol, and other major economies, such as the United Kingdom, Germany and France, have ruled out using carryover credits of their own. Indeed, this approach has been ruled out by the vast majority of countries. Last year, New Zealand climate minister James Shaw said claiming carryover credits was not in the spirit of the Paris Agreement, and that he “would discourage any country from using [them].” While developed countries are reluctant to call Australia out directly, during a peer-review process at UN climate talks in June this year both Canada and the EU raised concerns about Australia’s plans to use “credits” to meet its 2030 target.

Last month Australian foreign minister Marise Payne suggested Pacific island countries “should be pleased that Australia is meeting our Paris commitments, that is something we are absolutely locked into doing.” Less than a week later, leaders from eight Pacific island countries issued an emphatic response; they were most decidedly not pleased. Meeting in Fiji they endorsed a “Nadi Bay Declaration on the Climate Change Crisis in the Pacific.” In targeted language, island states called on parties to the Kyoto Protocol to “refrain from using “carryover credits as an abatement for the additional Paris Agreement emissions reduction targets.” Next week will be the first time in a decade that Bainimarama will attend the Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ meeting. It is clear that, even as he returns to the fold, he intends to take Australia to task. The wording of this year’s Forum communique, expected to call for greater action on climate change, will likely prove contentious. As Bainimarama has ominously warned: “we cannot allow climate commitments to be watered down in the meeting hosted by the nation whose very existence is threatened by the rising waters lapping at its shores”. Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga has himself said “we cannot be regional partners under this step-up initiative – genuine and durable partners — unless the government of Australia takes a more progressive response to climate change.”

Shaping Global Rules: the Pacific’s Long Fight for Survival

In May this year, the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres traveled to Tuvalu. Standing in waist-deep water, in his pinstripe suit, he called for a global end to new coal-fired power plants. He also called for all countries to bring more ambitious plans to reduce emissions to a special UN Climate Summit in New York on the 23 of September. He wants all countries to reduce emissions by 45 percent by 2030, and to aim for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Guterres issued his call from Tuvalu because the low-lying nation is at the frontline of climate impacts. However, he was also aware that Pacific island countries have led global efforts to tackle climate change for a generation. Island states were crucial for the negotiation of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Imperfect as it is, it remains the only multilateral mechanism we have to avoid cataclysmic changes to our planet. Under the agreement, countries must make more ambitious pledges to reduce emissions every five years. By this means, between now and mid-century, the world will transition to a net-zero emissions global economy. Pacific island states are looking for all countries to work towards this goal, including strengthening their current commitments, and they look especially to Australia, the largest and wealthiest member of the Pacific Islands Forum.

Soon after he came to power as prime minister, Morrison faced pressure to walk away from the Paris Agreement altogether. When he was interviewed by influential radio host Allan Jones in October 2018 he was asked why Australia shouldn’t just “rip up” the Agreement and say: “we’re out of it.” Morrison’s response was telling. He told Jones the Paris Agreement was “enormously important” to our island neighbours “who are strategic partners in the Pacific.” Morrison was right of course. Continued failure to address climate change, risks undermining cooperation with states that are increasingly important to Australia’s strategic interests.

Dr Wesley Morgan is an adjunct research fellow with the Griffith Asia Institute. Between 2016 and 2019 he was a lecturer in international affairs at the University of the South Pacific.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.